In early days in England there were miniature-painters, and in the last half of the sixteenth century there were some very important English painters of this kind. Before the days of Charles I. the English kings were much in the habit of inviting foreign artists to England, and commissions were given to them. The painters who were most prominent in England were of the Flemish school, and even under Charles I., as we have seen, Rubens and Vandyck were the principal painters in England. But in the reign of this king some native artists made names for themselves, and what we call the English school of painting may really be dated from this time.

Before speaking of painters I must mention one miniaturist whose works were in demand in other countries, as well as in England. Samuel Cooper (1609-1672) has been called “the Vandyck in little,” and there is far more breadth in his works than is usual in miniature. He painted likenesses of many eminent persons, and his works now have an honorable place in many collections.

William Dobson (1610-1646) has been mentioned in our account of Vandyck as a painter whom the great master befriended and recommended to Charles I. He became a good portrait-painter, and after Vandyck’s death was appointed sergeant-painter to the king. His portraits are full of dignity; the face shadows are dark, and his color excellent. He did not excel in painting historical subjects. Vandyck was succeeded at court by two foreign artists who are so closely associated with England that they are always spoken of as English artists.

Fig. 70.—Sir Joshua Reynolds.

Fig. 70.—Sir Joshua Reynolds.Peter van der Faes (1618-1680), who was born in Westphalia, is known to us as Sir Peter Lely. He became the most celebrated portrait-painter after Vandyck, and his “Beauties at Hampton Court” are pictures which are known the world over. He has been accused of not painting eyes as he ought; but the ladies of his day had an affectation in the use of their eyes. They tried to have “the sleepy eye that spoke the melting soul,” so Sir Peter Lely was not to blame for painting them as these ladies wished them to be. He was knighted by Charles II., and became very rich. His portraits of men were not equal to those of women. When Cromwell gave him a commission to paint his portrait, he said: “Mr. Lely, I desire you will use all your skill to paint my picture truly like me, and not flatter me at all; but remark all these roughnesses, pimples, warts, and everything as you see me, otherwise I will never pay you a farthing for it.” Sir Peter Lely was buried in Covent Garden, where there is a monument to his memory with a bust by Gibbon.

Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723), born at Lübeck, was a rival to Sir Peter Lely, and had the honor of painting the portraits of eight crowned heads and a very great number of other people of importance. He had studied both the Dutch and Italian manner; for he was the pupil of Rembrandt and Bol, of Carlo Maratti and Bernini. Some critics praise his pictures very much, while others point out many defects in them. He painted very rapidly, and he sometimes hurried his pictures off for the sake of money; but his finished works are worthy of remark. He especially excelled in painting hair; his drawing was correct; some of his groups of children are fine pictures; and some madonnas that he painted, using his sitters as models, are works of merit. His monument was made by Rysbrach, and was placed in Westminster Abbey.

Both Sir Peter Lely and Sir Godfrey Kneller had pupils and followers; but there was no original English artist before the time of William Hogarth (1697-1764), and he may really be named as the first master of a purely English school of painting. When Hogarth was fifteen years old he was apprenticed to a silversmith, and the grotesque designs which he copied for armorial bearings helped to increase his natural love for all that was ridiculous and strange. After 1718 he was much occupied in engraving for booksellers, and at length he began to paint small genre pictures and some portraits, in which he made good success, but he felt that he was fitted for other work. In 1730 he married the daughter of the artist, Sir James Thornhill, without the consent of her father.

Soon after this he began his series of pictures called the “Harlot’s Progress,” and when Sir James saw them he was so satisfied with the talent of Hogarth that he declared that such an artist could support a wife who had no dower, and the two painters were soon reconciled to each other. Before 1744 Hogarth had also painted the series of the “Rake’s Progress” and “Marriage à la Mode” (Fig. 71).

These are all pictures which hold up the customs of the time to ridicule and satire, and his works of this kind are almost numberless. He explains as follows the cause of his painting in this way: “The reasons which induced me to adopt this mode of designing were that I thought both critics and painters had, in the historical style, quite overlooked that intermediate species of subjects which may be placed between the sublime and the grotesque. I therefore wished to compose pictures on canvas similar to representations on the stage; and further hope that they will be tried by the same test and criticised by the same criticism.”

Fig. 71.—The Marriage Contract. No. 1 of The Marriage à la Mode. By Hogarth. In the National Gallery.

Fig. 71.—The Marriage Contract. No. 1 of The Marriage à la Mode. By Hogarth. In the National Gallery.It was in this sort of picture that Hogarth made himself great, though he supported himself for several years by portrait-painting, in which art he holds a reputable place. Most of his important pictures are in public galleries.

Hogarth was a fine engraver, and left many plates after his own works, which are far better and more spirited than another artist could have made them. The pictures of Hogarth have good qualities aside from their peculiar features. He made his interiors spacious, and the furniture and all the details were well arranged; his costumes were exact, as was also the expression of his faces; his painting was good, and his color excellent. In 1753 he published a book called the “Analysis of Beauty.”

Ever after his first success his career was a prosperous one. He rode in his carriage, and was the associate and friend of men in good positions. Hogarth was buried in Chiswick Churchyard, and on his tombstone are these lines, written by David Garrick:

“Farewell, great painter of mankind!

Who reach’d the noblest point of Art,

Whose pictur’d morals charm the mind,

And through the eye, correct the heart.

If Genius fire thee, reader, stay;

If Nature touch thee, drop a tear;

If neither move thee, turn away,

For Hogarth’s honour’d dust lies here.”

The next important English painter was Richard Wilson (1713-1782), and he was important not so much for what he painted as for the fact that he was one of the earliest landscape-painters among English artists. He never attained wealth or great reputation, although after his return from studying in Italy he was made a member of the Royal Academy.

We come now to Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), born at Plympton, in Devonshire. His father was a clergyman and the master of the grammar school at Plympton. Joshua was destined for the medical profession by his parents; but his love of drawing was so marked that, as the opportunity offered for him to go to London and study under Hudson, his father allowed him to do so. After various changes, in 1749 he was able to go to Rome, and remained in Italy three years (Fig. 70).

When he returned to England he soon attracted attention to his pictures, and it was not long before both fame and fortune were secured to him. His life was a very quiet one, with little of incident that can be related here. His sister kept his house for him, and he lived generously, having company to dinner almost daily. His friends were among the best people of the time, including such persons as Dr. Johnson, Percy, Goldsmith, Garrick, the Burkes, and many others. The day before Johnson died he told Reynolds that he had three requests to make of him: that he would forgive him thirty pounds which he had lent him, would read the Scriptures daily, and would not paint on Sunday. Sir Joshua promised to do these things, and remembered his promise.

Sir Joshua was skilful in compliments. When he painted his famous picture of Mrs. Siddons as the “Tragic Muse” he put his name on the border of her garment. The actress went near the picture to examine it, and when she saw the name she smiled. The artist said: “I could not lose the opportunity of sending my name to posterity on the hem of your garment.”

Fig. 72.—“Muscipula.” By Reynolds.

Fig. 72.—“Muscipula.” By Reynolds.Sir Joshua Reynolds’ fame rests upon his portraits, and in these he is almost unrivalled. His pictures of children are especially fine. It was his custom to receive six sitters daily. He kept a list of those who were sitting and of others who waited for an opportunity to have their portraits made by him. He also had sketches of the different portraits he had painted, and when new-comers had looked them over and chosen the position they wished, he sketched it on canvas and then made the likeness to correspond. In this way, when at his best, he was able to paint a portrait in about four hours. His sitters’ chairs moved on casters, and were placed on a platform a foot and a half above the floor. He worked standing, and used brushes with handles eighteen inches long, moving them with great rapidity.

In 1768 Sir Joshua was made the first President of the Royal Academy, and it was then that he was knighted by the king. He read lectures at the Academy until 1790, when he took his leave. During these years he sent two hundred and forty-four pictures to the various exhibitions. In 1782 he had a slight shock of paralysis, but was quite well until 1789, when he feared that he should be blind, and from this time he did not paint. He was ill about three months before his death, which occurred in February, 1792. His remains were laid in state at the Royal Academy, and then buried in St. Paul’s Cathedral, near the tomb of Sir Christopher Wren.

It is to be regretted that the colors used by Sir Joshua Reynolds are now much faded in many of his pictures. Those in the National Gallery, in London, are, however, in good preservation. Naturally, since so many of his pictures were portraits they are in the collections of private families in England, and but few of them are seen in European galleries. There is an excellent opportunity to study his manner in the pictures at the South Kensington Museum, where there are several portraits, some pictures of children, and the “Graces Decorating a Statue of Hymen.”

It is very satisfactory to think of a great artist as a genial, happy man, who is dear to his friends, and has a full, rich life outside of his profession. Such a life had Sir Joshua Reynolds, and one writer says of him: “They made him a knight—this famous painter; they buried him ‘with an empire’s lamentation;’ but nothing honors him more than the ‘folio English dictionary of the last revision’ which Johnson left to him in his will, the dedication that poor, loving Goldsmith placed in the ‘Deserted Village,’ and the tears which five years after his death even Burke could not forbear to shed over his memory.”

Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788) was born in Sudbury, in Suffolk, and when still quite young went to London, and studied under Francis Hayman, who was not an eminent painter. Gainsborough became one of the most important masters of the English school, especially in landscape painting and the representation of rustic figures. His portraits were not as good in color as those of Sir Joshua Reynolds; they have a bluish-gray hue in the flesh tints; but they are always graceful and charming. His landscapes are not like those of any other master. They are not exact in the detail of leaves and flowers—a botanist could find many faults in them—but they are like nature in spirit: they seem to have the air blowing through them, they are fresh and dewy when it is morning in them, and quiet and peaceful when evening comes under his brush. In many of his pictures he put a cart and a white animal.

His rustic figures have the true country life in them: they seem to have fed upon the air, and warmed themselves in the sun until they are plump and rosy as country lads and lasses should be. His best genrepictures are the “Cottage Girl,” the “Woodman and Dog in a Storm,” the “Cottage Door,” and the “Shepherd Boy in a Shower.” He painted a picture of a “Girl and Pigs,” for which Sir Joshua Reynolds paid him one hundred guineas.

In character Gainsborough was very attractive, though somewhat contradictory in his moods. He was generous and genial, lovable and affectionate; he was also contradictory and impulsive, not to say capricious. His wife and he had little quarrels which they settled in this wise: When Gainsborough had spoken to her unkindly, he would quickly repent, and write a note to say so, and address it to his wife’s spaniel, called “Tristram,” and sign it with the name of his pet dog, “Fox.” Then Margaret Gainsborough would answer: “My own, dear Fox, you are always loving and good, and I am a naughty little female ever to worry you as I too often do, so we will kiss, and say no more about it; your own affectionate Tris.” Like Reynolds, Gainsborough had many warm friends, and when he died Sir Joshua himself watched by his bedside, and bent to catch his last word, which was the name of Vandyck.

John Singleton Copley (1737-1815) was born in Boston, Mass., U. S., to which place his parents are said to have immigrated from Limerick, Ireland. The father was descended from the Copleys of Yorkshire, England, and the mother from the Singletons of County Clare, both families of note. When young Copley was eleven years old his mother was married to Peter Pelham, a widower with three sons—Peter, Charles, and William—and who subsequently became the father of another son, Henry, by this second marriage. Mr. Pelham was a portrait painter and a mezzotint engraver of unusual merit. One authority calls him “the founder of those arts in New England.” Mr. Pelham was also a man of education, a land surveyor, and a mathematician. He was thus well qualified to educate, assist, and stimulate young Copley in the pursuit of studies so natural and congenial to him. He is said to have been studious and quiet, and to have made rapid advances. When he was fifteen years old he painted a portrait of his step-brother, Charles Pelham, now in the family of a great-grandson, Mr. Charles Pelham Curtis, of Boston. At sixteen he published an engraving of Rev. William Welsteed, from a portrait painted by himself. The same year he painted the portrait of a child—afterward Dr. de Mountfort—now owned in Detroit. In 1754 he painted an allegorical picture of Mars, Venus, and Vulcan, thirty inches long by twenty-five wide, now owned in Bridgewater, Mass. The next year he painted a miniature of George Washington, who was on a visit to Governor Shirley at the time. This picture now belongs to the family of the late George P. Putnam, of New York City. In 1756 he painted a three-quarters length portrait of General William Brattle, life size, signed and dated, and now owned by Mr. William S. Appleton. He now improved rapidly. A crayon portrait of Miss Rebecca Gardiner, afterward Mrs. Philip Dumaresq, an oil painting of Mrs. Edmund Perkins, a portrait of Rebecca Boylston, afterward wife of Governor Gill, portraits of Colonel and Mrs. Lee, grandparents of General William Raymond Lee, all exist and attest the continued growth of his powers. These date between 1763 and 1769. During this time he had access to and was a visitor in houses where were portraits by Saribest, Blackburn, Liopoldt, and even by Vandyck and Sir Godfrey Kneller. Mr. Augustus Thorndike Perkins, in his carefully written monograph on Copley, says that our artist must have seen all these pictures, since, as Dr. Gardiner says, “his genial disposition and his courtly manners make him a welcome guest everywhere.” Mr. Perkins remarks that Copley must have studied with Blackburn; that he imitated, but in some respects surpassed him. “Both frequently used, either as the lining of a dress or as drapery, a certain shade of mauve pink; Blackburn uses this shade feebly, while Copley dashes it on with the hand of a master.” On November 16, 1769, Copley married Susan (or Susannah, as it is sometimes written), the daughter of Mr. Richard Clarke, a distinguished merchant of Boston, to whom, as agent of the East India Company of London, was consigned the tea thrown overboard in Boston harbor. From all accounts he soon began to live in good style; and as, in 1771, Colonel Trumbull found him living opposite the Common, it is probable that he purchased at about that time the property which afterward became so valuable, although long after Copley had ceased to be the owner. In 1773, says the late eminent conveyancer, Nathaniel Ingersoll Bowditch, “Copley owned all the land bounded on the west by Charles River, thence by Beacon Street to Walnut Street, thence by Walnut Street to Mt. Vernon Street, thence by Mt. Vernon Street to Louisburg Square, thence by Louisburg Square to Pinckney Street, thence by Pinckney Street to the water, containing about eleven acres of land.” This land is now covered with handsome residences, and is of great value. An agent of Copley’s sold his property after he went abroad without being authorized to do so, and, although his son came over in 1795 to look into the matter, he was only able to secure a compromise by which a further sum of three thousand guineas was paid in final settlement.

Soon after his marriage Copley painted his picture of a “Boy with a Squirrel,” which he sent anonymously to Benjamin West, in London, for exhibition. West judged from the wood on which the picture was stretched and from the kind of squirrel that the work was American, and so excellent was the painting that a rule of the institution was set aside, and the picture exhibited. This picture is now in the possession of Mrs. James S. Amory, of Boston, a granddaughter of the artist. The boy in the picture was his half-brother Henry. The picture was so favorably received that Copley was advised to go to England. He sailed in 1774, and never returned.

Mr. Copley, soon after his arrival in London, passed over to the Continent, and through Italy, studying in Parma and in Rome. He visited Naples and Pæstum also. It is said that he studied so diligently that he was with difficulty persuaded to paint two portraits in Rome. In 1775 he travelled and studied in Germany, in Holland, and in France. This same year his wife and family joined him in England. These consisted of his wife, his son, John Singleton, who afterward became the famous Lord Chancellor Lyndhurst; his daughter Elizabeth, afterward married to a distinguished merchant in Boston, and who survived to a great age; Mary Copley, who lived unmarried to the great age of ninety-four; and another son who died young. In 1777 he was made an Associate of the Royal Academy, and six years later an Academician. He was now in the full tide of success. He was offered five hundred guineas to paint a family group of six persons. The well-known group of Copley’s family, called the “Family Picture,” the “Death of Lord Chatham,” and “Watson and the Shark,” were on his easel in 1780. The picture of Lord Chatham falling senseless in the House of Lords was commenced soon after his death in 1778. It was engraved by Bartolozzi, and twenty-five hundred copies were sold in a few weeks. Copley exhibited the picture, to his own profit as well as fame.

In 1781 occurred the death of Major Pierson, shot in the moment of victory over the French troops who had invaded the island of Jersey. His death was instantly avenged by his black servant, and of this scene Copley made one of his finest pictures. He took pains, with his usual honesty, to go to St. Helier’s, and make a drawing of the locality. The picture is thoroughly realistic, although painful. His large picture of the “Repulse and Defeat of the Spanish Floating Batteries at Gibraltar” was painted on commission from the city of London. It is twenty-five feet long by twenty-two and a half feet high; but there are so many figures and so much distance to be shown in the painting that the artist really needed more room. Of the commander, Lord Heathfield, Sir Robert Royd, Sir William Green, and some twelve or fifteen others, the artist made careful portraits.

The story told by Elkanah Watson shows Copley’s strong sympathy for America. In 1782 Watson was in London, and Copley made a full-length portrait of him, and in his journal Watson says: “The painting was finished in most exquisite style in every part, except the background, which Copley and I designed to represent a ship bearing to America the acknowledgments of our independence. The sun was just rising upon the stripes of the Union streaming from her gaff. All was complete save the flag, which Copley did not deem proper to hoist under the present circumstances, as his gallery was the constant resort of the royal family and the nobility. I dined with the artist on the glorious 5th of December, 1782. After listening with him to the speech of the king formally recognizing the United States of America as in the rank of nations, previous to dinner, and immediately after our return from the House of Lords, he invited me into his studio, and there, with a bold hand, a master’s touch, and, I believe, an American heart, he attached to the ship the stars and stripes. This was, I imagine, the first American flag hoisted in Old England.”

Copley purchased, for a London residence, the mansion-house in George Street belonging to Lord Fauconburg. It afterward became more widely known as the residence of his son, Lord Lyndhurst. Lord Mansfield’s residence was near by, and among the many commissions from public men was one to paint his lordship’s portrait. Perhaps one of the most interesting of all his commissions was one to paint the picture of Charles I. demanding the five obnoxious members from the Long Parliament, for which a number of gentlemen in Boston paid one thousand five hundred pounds. It is said that every face in this great picture was taken from a portrait at that time extant; and Mrs. Gardiner Greene narrates that she and her father were driven in a post-chaise over a considerable part of England, visiting every house in which there was a picture of a member of the famous Parliament, and were always received as honored guests. Copley’s painting of the death of Lord Chatham was much admired. So numerous were the subscriptions for the engraving that it is said Copley must have received nearly, or quite, eleven thousand pounds for the picture and the engraved copies. It was quite natural for Copley to be popular with New Englanders; indeed, almost every Bostonian, at one time, on visiting London, made a point to bring home his portrait by Copley, if possible. There are known to exist in this country two hundred and sixty-nine oil-paintings, thirty-five crayons, and fourteen miniatures by him. These pictures are carefully cherished, as are indeed all memorials of this generous and kindly gentleman. Although his life was mostly passed in England, where he obtained wealth and renown, yet in a strong sense he could be claimed for Boston, as it was there he was born; it was there he received his artistic bias and education; it was there he was married, and had three children born to him; and, finally, it was there that he acquired a fair amount of fame and property solely by his brush. It will be worth while for the readers of this volume to take pains to see some of the more noteworthy Copleys.

A portrait of John Adams, full length, painted in London in 1783, is now in possession of Harvard College. A portrait of Samuel Adams, three-quarters length, spirited and beautiful, standing by a table, and holding a paper, hangs in Faneuil Hall. Another picture of Samuel Adams is in Harvard College, which also owns several other Copleys. A portrait of James Allen, a man of fortune, a patriot, and a scholar, is now owned by the Massachusetts Historical Society. The “Copley Family,” one of the artist’s very best pictures, is now owned in Boston by Mr. Amory, and, in fact, Mrs. James S. Amory owns a number of his best works.

Copley was a man of elegance and dignity, fond of the beautiful, particular in his dress, hospitable, and a lover of poetry and the arts. His favorite book was said to be “Paradise Lost.” His last picture was on the subject of the Resurrection.

Benjamin West (1738-1820) was born at Springfield, Pennsylvania, of Quaker parentage. In the various narratives of his successful life many stories are told which appear somewhat fabulous, and most of which have nothing to do with his subsequent career. He is said to have made a pen-and-ink portrait of his little niece at the age of seven years; to have shaved the cat’s tail for paint brushes; to have received instruction in painting and archery from the Indians; to have so far conquered the prejudices of his relatives and their co-religionists to his adoption of an artist’s life that he was solemnly consecrated to it by the laying on of hands by the men, and the simultaneous kissing of the women. His love for art must have been very strong, and he was finally indulged, and assisted in it by his relatives, so that at the age of eighteen he was established as a portrait-painter in Philadelphia. By the kindness of friends in that city and in New York he was enabled to go to Italy, where he remained three years, making friends and reputation everywhere. Parma, Florence, and Bologna elected him a member of their Academies. He was only twenty-five years old when he went to England, on his way back to America. But he was so well received that he finally determined to remain in England, and a young lady named Elizabeth Shewell, to whom he had become engaged before going abroad, was kind and judicious enough to join him in London, where she became his wife, and was his faithful helpmate for fifty years. In 1766 he exhibited his “Orestes and Pylades,” which on account of its novelty and merit produced a sensation. He painted “Agrippina weeping over the Urn of Germanicus,” and by the Archbishop of York was introduced to George III. as its author. He immediately gained favor with the king, and was installed at Windsor as the court-painter with a salary of one thousand pounds per annum. This salary and position was continued for thirty-three years. He painted a series of subjects on a grand scale from the life of Edward III. for St. George’s Hall, and twenty-eight scriptural subjects, besides nine portrait pictures of the royal family. In 1792, on the death of Reynolds, he was elected President of the Royal Academy, a position which, except a brief interregnum, he held until his death in March, 1820. He was greatly praised in his day, and doubtless thought himself a great artist. He painted a vast number of portraits and quite a number of pictures of classical and historical subjects. His “Lear” is in the Boston Athenæum; his “Hamlet and Ophelia” is in the Longworth collection in Cincinnati; “Christ Healing the Sick” is in the Pennsylvania Hospital; and the “Rejected Christ” is or was owned by Mr. Harrison, of Philadelphia. There are two portraits of West, one by Allston and one by Leslie, in the Boston Athenæum, and a full-length, by Sir Thomas Lawrence, in the Wadsworth Gallery in Hartford, Conn. One of West’s pictures did a great deal for his reputation, although it was quite a departure from the treatment and ideas then in vogue; this was the “Death of General Wolfe” on the Plains of Abraham. When it was known to artists and amateurs that his purpose was to depict the scene as it really might have happened he was greatly ridiculed. Even Sir Joshua Reynolds expressed an opinion against it; but when he saw the picture he owned that West was right. Hitherto no one had painted a scene from contemporary history with figures dressed in the costume of the day. But West depicted each officer and soldier in his uniform, and gave every man his pig-tail who wore one. The picture is spirited and well grouped. West was just such a practical, thoughtful, and kindly man as we might expect from his ancestry and surroundings.

George Romney (1734-1802), born in Beckside, near Dalton, in Cumberland. He married when he was twenty-two, and in his twenty-seventh year went to London with only thirty pounds in his pocket, leaving his wife with seventy pounds and two young children. He returned home to die in 1799, and in the meantime saw his wife but twice. The year after his arrival in London he carried off the fifty-guinea prize on the subject of the “Death of Wolfe” from the Society of Arts. Through the influence of Sir Joshua Reynolds this was reconsidered, and the fifty-guinea prize was awarded to Mortimer for his “Edward the Confessor,” while Romney was put off with a gratuity of twenty-five guineas. This produced a feud between the two artists. Romney showed his resentment by exhibiting in a house in Spring Gardens, and never sending a picture to the Academy, while Reynolds would not so much as mention his name, but spoke of him as “the man in Cavendish Square.” This was after his return from the Continent; but before going to Italy he was distinctly the rival of Sir Joshua, so much so that there were two factions, and Romney’s studio, in Great Newport Street, was crowded with sitters, among whom was the famous Lord Chancellor Thurlow, whose full-length portrait is the pride of its possessor. At this time he was making about twelve hundred pounds a year, a very good income for those days. In 1773 he went to Rome with a letter to the Pope from the Duke of Richmond. His diary, which he kept for a friend, shows how conscientious and close was his observation and how great his zeal. He made a copy of the “Transfiguration,” for which he refused one hundred guineas, and which finally sold for six guineas after his death. On his return to London in 1775 he took the house in Cavendish Square, where he had great success. He painted a series of portraits of the Gower family, the largest being a group of children dancing, which Allan Cunningham commended as being “masterly and graceful.” Some of his portraits have a charm beyond his rivals. He painted portraits of Lady Hamilton, the friend of Lord Nelson—“the maid of all work, model, mistress, ambassadress, and pauper”—scores of times, and in different attitudes and a variety of characters, as Hebe, a Bacchante, a Sibyl, as Joan of Arc, as “Sensibility,” as a St. Cecilia, as Cassandra, as Iphigenia, as Constance, as Calypso, as Circe, and as Mary Magdalen, and in some of these characters many times. He often worked thirteen hours a day, and did his fancy sketches when sitters disappointed him. He would paint a portrait of a gentleman in four sittings. He was extremely fond of portraying Shakespeare’s characters, and contributed to the Shakespeare Gallery formed by Alderman Boydell. He went to Paris in 1790, where Lord and Lady Gower introduced him to Louis Philippe, and through him to all the art treasures of the French capital. On his return to London he formed a plan of an art museum, to be furnished with casts of the finest statues in Rome, and spent a good deal of money in the erection of a large building for the purpose. His powers as an artist gradually waned. He left his Cavendish Square residence in 1797, and in 1799 returned to his family and home at Kendall. From this time to the close of his life in 1802 he was a mere wreck, and his artist life was over.

George Morland (1763-1804) was born in London, and the son of an artist. His father was unsuccessful, and poor George was articled to his father, after the English fashion, and was kept close at home and at work. It is said that his father stimulated him with rich food and drink to coax him to work. He was very precocious, and really had unusual talents. His subjects were those of rustic life, and his pictures contain animals wonderfully well painted, but his pigs surpass all. His character was pitiful; he was simply, at his best, a mere machine to make pictures. As for goodness, truth, or nobleness of any sort, there is not a syllable recorded in his favor. Strange to say, the pictures of his best time are masterpieces in their way, and have been sold at large prices.

Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830), born at Bristol, England, in the White Hart Inn, of which his father was landlord. He was wonderfully precocious, and as a child of five years would recite odes, and declaim passages from Milton and Shakespeare. Even at this early period he made chalk or pencil portraits, and at nine he finally decided to become a painter from having seen a picture by Rubens. At this period he made a colored chalk portrait of the beautiful Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, which still hangs in Chiswick House, in the room in which Charles Fox died. His father was the son of a clergyman, and was bred a lawyer, but had never prospered; still his culture and education gave a certain zest and tone to the mind of young Lawrence, and made him, with his elegant figure and handsome face, the successful courtier that he afterward became. He worked hard, with considerable success, and with but little instruction until, at the age of eighteen, he went to London for the first time. At that period he was described as being extremely handsome in person, with fine, regular features, brilliant eyes, and long, chestnut-colored hair falling to his shoulders. He lodged close by Sir Joshua Reynolds—then near the end of his career, and from him received much valuable advice. During Lawrence’s first years in London he attempted pictures illustrating classic art, but without much success. Indeed he was never successful in large, imaginative pictures, and during most of his career of more than forty years, confined himself to portraits. The time was propitious for him: Gainsborough was dead; Reynolds was almost blind, and had given up painting; and Romney had no hold on the court and the leaders of fashion. Lawrence raised his prices, and had all he could do. He adopted a more expensive style of dress, and in fact lived so extravagantly that he never arrived at what may be called easy circumstances—his open-handed generosity contributed to this result. He early received commissions from the royal family. In 1791 he was elected an Associate, and in 1794 an Academician. The next year George III. appointed him painter in ordinary to his Majesty. He was thus fairly launched on a career that promised the highest success. In a certain sense he had it, but largely in a limited sense. He painted the portraits of people as he saw them; but he never looked behind the costume and the artificial society manner. He reproduced the pyramidically shaped coats and collars, the overlapping waistcoats of different colors, the Hessian boots, and the velvet coats, adorned with furs and frogs, of the fine gentlemen; and the turbans with birds-of-Paradise feathers, the gowns without waists, the bare arms and long gloves, the short leg-of-mutton sleeves, and other monstrosities of the ladies. And for thirty years his sitters were attired in red, or green, or blue, or purple. He absolutely revelled in the ugliness of fashion. Occasionally Lawrence did some very good things, as when he painted the Irish orator and patriot, Curran, in one sitting, in which, according to Williams, “he finished the most extraordinary likeness of the most extraordinary face within the memory of man.” He always painted standing, and often kept his sitters for three hours at a stretch, and sometimes required as many as nine sittings. On one occasion he is said to have worked all through one day, through that night, the next day, and through all the night following! By command of the prince regent he painted the allied sovereigns, their statesmen, princes, and generals—all the leading personages, in fact, in alliance against Napoleon. His pictures in the exhibition of 1815 were Mrs. Wolfe, the Prince Regent, Metternich, the Duke of Wellington, Blucher, the Hetman Platoff, and Mr. Hart Davis. During the Congress that met at Aix-la-Chapelle in 1818, Lawrence was commissioned by the Prince Regent to paint its principal heads for an especial gallery. He thus had for sitters nearly all the leading statesmen of Europe. From Aix-la-Chapelle he went to Vienna, and thence to Rome in 1819, where among others he painted likenesses of the Pope, of Cardinal Gonsalvi, and of Canova. Of the latter, Canova cried out, “Per Baccho, che nomo e questo!” It was considered a marvellous likeness; and without violating good taste he worked into the picture crimson velvet and damask, gold, precious marble, and fur, with a most brilliant effect. Before reaching home in London he was elected President of the Royal Academy. At this time he had been elected a member of the Roman Academy of St. Luke’s, of the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence, and of the Fine Arts in New York. He continued to improve as a painter, and between 1825 and the year of his death, painted and exhibited some of his finest works. He usually exhibited eight pictures each year, and although without a rival, gave evidence of anxious care to sustain his reputation. He was especially successful with children, and many of these pictures—as well as of celebrities—were engraved, and have thus become known all over the world. Of his eight pictures exhibited in 1829—the last he ever contributed—Williams says: “It is difficult to imagine a more undeviating excellence, an infallible accuracy of likeness, with an elevation of art below which it seemed impossible for him to descend.” Lawrence died on the morning of the 7th of January, 1830, with but little warning, from ossification of the heart; he was buried with much pomp and honor in St. Paul’s Cathedral, by the side of Sir Joshua Reynolds.

Fig. 73.—Portrait of Turner.

Fig. 73.—Portrait of Turner.Joseph M. W. Turner, R.A. (1775-1851).—It is believed, by those who have investigated the question most carefully, that this eminent artist and most remarkable man was born in Maiden Lane, London, April 3, 1775, although the artist himself has stated that he was born in Devonshire, April 23, 1769. Turner’s father, William Turner, was a native of Devonshire, but came to London while young, and did a fair business in the Covent Garden district as a hair-dresser, wig-maker, and in shaving people. The father was garrulous, like the traditional hair-dresser, with a pleasant laugh, and a fresh, smiling face. He had a parrot nose and a projecting chin. Turner’s mother was a Miss Mallord (or Marshall), of good family, but a violent-tempered woman, with a hawk nose and a fierce visage. Her life ended in a lunatic asylum. The artist, who was always impatient of inquiry into his domestic matters, resented any allusion to his mother, and never spoke of her. The manifest peculiarities of his parents had an impression upon Turner, and would have made him eccentric had there been no other influences of a kindred nature. The parents were under-sized, and of limited mental range; they were of very little personal assistance to their gifted son, although the father in later years busied himself in mixing colors, adjusting pictures to frames, and sometimes he was entrusted with certain rough work at filling in backgrounds. When Turner was but five years old he is said to have made, from memory, a fair copy of a lion rampant engraved on a silver salver, which he had seen while accompanying his father to the house of a customer. Presently the boy began to copy pictures in water-colors, and then to make sketches from nature of scenes along the river Thames. In his ninth year he drew a picture of Margate Church. When he was ten years old he was sent to school at Brentford-Butts, where he remained two years, boarding with his uncle, the local butcher. His leisure hours were spent in dreamy wanderings and in making countless sketches of birds, trees, flowers, and domestic fowls. He acquired a smattering of the classics and some knowledge of legends and ancient history. On his return to London he received instruction from Palice in painting flowers, and, after a year or two, was sent to Margate, in Kent, to Coleman’s school. Here he had more scope and a wider range, and made pictures of the sea, the chalk cliffs, the undulations of the coast, and the glorious effects of cloud scenery. On his return from Margate he began to earn money by coloring engravings and by painting skies in amateurs’ drawings and in architects’ plans at half a crown an evening. He always deemed this good practice, as he thus acquired facility and skill in gradations. His father at one time thought to make an architect of him, and sent him to Tom Malton to study perspective. But he failed in the exact branch of the profession, and neither with Malton nor with the architect Hardwick did he give satisfaction. While with Hardwick he drew careful sketches of old houses and churches, and this practice must have been of much use to him in after-life. His father finally sent him to the Royal Academy, where he studied hard, drawing from Greek models and the formal classic architecture. About this time he was employed, at half a crown an evening, with supper thrown in, to make copies of pictures by Dr. Munro, of Adelphi Terrace. Munro was one of the physicians employed in the care of George III. when he had a crazy spell, and owned many valuable pictures by Salvator-Rosa, Rembrandt, Snyder, Gainsborough, Hearne, Cozens, and others. He had also portfolios full of drawings of castles and cathedrals, and of Swiss and Italian scenery, and of sketches by Claude and Titian. Turner was also employed to sketch from nature in all directions about London. In these tasks he had for a constant companion “Honest Tom Girtin,” a young fellow of Turner’s own age, who afterward married a wealthy lady, had rich patrons, and died before he was thirty. Had he lived to mature years, Girtin would have been a powerful rival to Turner. They were most excellent friends, and when Girtin died in Rome, Turner was one of his most sincere mourners. Toward the close of Sir Joshua Reynolds’ life, Turner frequented his studio, copied pictures, and acquired some art secrets. He began to teach water-color drawing in schools, while still a boy, at from a crown to a guinea a lesson. He made hundreds of sketches in a part of London now built over compactly with houses in streets and squares, but then picturesque in hills and dells, in wooded fields and green lanes. With all his baggage tied in a handkerchief on the end of his walking-stick, he made a sketching tour through the towns of Rochester, Canterbury, Margate, and others, in Kent, in 1793, and about this time began to paint in oil. His first contribution to the Royal Academy was a water-color sketch in 1790. Within the next ten years he exhibited over sixty pictures of castles, cathedrals, and landscapes. All through his life he made sketches. Wherever he was, if he saw a fine or an unusual effect, he treasured it up for use. He sketched on any bit of paper, or even on his thumb-nail, if he had nothing better. Nothing escaped his attention, whether of earth, or sea, or sky. Probably no artist that ever lived gave nature such careful and profound study. His studies of cloud scenery were almost a revelation to mankind. In all this Turner drew his instruction as well as his inspiration from nature. The critics did nothing for him; he rather opened the eyes of even such men as Ruskin to the wonders of the natural world. But these results all came later, and were the fruit of and resulted from his constant and incessant studies.

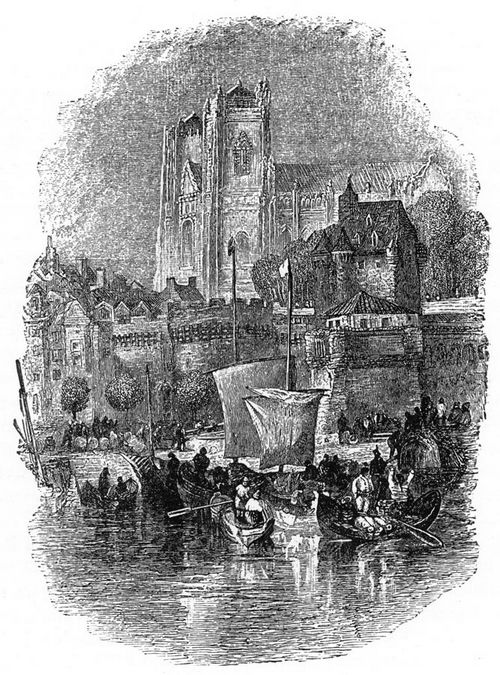

Fig. 74.—Nantes. By Turner.

Fig. 74.—Nantes. By Turner.In 1794 and 1795 he made elaborate drawings of Rochester, Chepstow, Birmingham, Worcester, Guildford, Cambridge, and other towns, for magazines. In 1796 he did the same for Chester, Bristol, Leith, Peterborough, and Windsor. Within the next four years he completed the circuit of twenty-six counties in England and Wales, and he also exhibited twenty-three highly finished drawings of cathedrals and churches. He was slow to undertake oil-painting, preferring the more rapid touch and the light-and-shade effect of the crayon, or the delicate and beautiful effects of water-colors. He was always greater as a painter in water-colors than in oils, and it is claimed by Redgrave that “the art all but began with him,” and that his water-color paintings “epitomize the whole mystery of landscape art.” Some of his paintings in this line have been sold at enormous prices, and even in his own day his water-color picture of Tivoli sold for eighteen hundred guineas. Turner became as fond of Northern Yorkshire—which he first visited in 1797—as he was of Southern Kent. He found there a great variety of scenery, from the sweet and peaceful to the ennobling and grand. He visited and made studies from all the old cathedrals, castles, and abbeys, and in 1798 he exhibited pictures of Fountain and Kirkstall Abbeys, Holy Island Cathedral, Buttermere Lake, Dunstanborough Castle, as well as “Morning Among the Corriston Fells.” He found in Yorkshire also some of his warmest friends and most munificent patrons, notably Mr. Hawkesworth Fawkes, of Farnley Hall, whose house was adorned with fifty thousand dollars’ worth of Turner’s pictures. Some additions to Farnley Hall were designed by Turner, and he was always a welcome visitor. Here he sketched, and at intervals enjoyed himself greatly in hunting and fishing. It is said that the Farnley portfolios still contain sketches not only of the hall and its precincts, but of coast scenes, Swiss views, drawings of birds, illustrations of the Civil War, and, more especially, of fifty-three remarkable drawings of the Rhineland regions, done at the rate of three a day; these last were offered by Turner to Mr. Fawkes on his return from the Continent for the sum of five hundred pounds, and the bargain was closed at once. When Mr. Fawkes visited London he spent hours in Turner’s private gallery, but was never shown into the painting-room. Indeed, very few persons were ever allowed there. Once, when Turner dined at a hotel with Mr. Fawkes, the artist took too much wine, and reeled about, exclaiming, “Hawkey, I am the real lion—I am the great lion of the day, Hawkey.” When Mr. Fawkes died, ended Turner’s visits to Farnley. He never went there again, but when the younger Fawkes brought the Rhine drawings up to London for him to see again, he passed his hand over the “Lorelei Twilight,” saying, with tears in his eyes, “But Hawkey! but Hawkey!” When Mr. Wells, an artist of Addiscomb, died he mourned his loss bitterly, and exclaimed to his daughter: “Oh, Clara, Clara, these are iron tears! I have lost the best friend I ever had in my life!” In this family all the children loved him. He would lie on the floor, and play with them, and the oldest daughter afterward said: “Of all the light-hearted, merry creatures I ever knew, Turner was the most so.” But in 1797 Turner had a bitter disappointment which warped and distorted all his after-life. A young lady to whom he had become attached while a schoolboy at Margate, was engaged to be married to him. He had been absent for two years on sketching tours, and the step-mother of the young lady had intercepted and destroyed his letters, so that at last she believed the representations made that Turner had deserted her. She became engaged to another, and was about to be married, when Turner appeared, and pleaded passionately that she would return to him. She thought that she had been trifled with, and held by her refusal, and did not find out the wrongs done by the step-mother until it was too late. This disappointment led to greater self-concentration and stingy money-getting until it became the absorbing passion of his life, so that the artist passion was dominated by it.

It would take up too large a portion of this book to describe even briefly Turner’s travels and works. Only a bare outline can be given. In 1800 he became an Associate of the Royal Academy. He moved into a more commodious house at 64 Harley Street. During this year he exhibited pictures of Caernarvon Castle and the “Fifth Plague of Egypt;” also fine views of Fonthill Abbey, the new palace of Beckford, with whom he spent much time. The only portrait for which Turner ever sat was painted in 1800 by George Dance. It shows a handsome young man, with a full but receding forehead, arched eyebrows, a prominent nose, a massive chin, and a sensual mouth. His thick and wiry hair is tied behind, and he wears a coat with an immense cape. By this time full-bottomed wigs had gone out of fashion, and the old barber abandoned his business to go and live with his artist son. In 1801 Turner exhibited pictures of St. Donat’s Castle and Pembroke Castle in Wales, the Salisbury Chapter-house, an autumn morning in London, the destruction of the Median army, and Dutch fishing-boats in a gale. He had begun his contest with Claude by painting pictures of classical subjects in Claude’s manner. Turner was elected Royal Academician in 1802, and exhibited several notable oil-paintings, signed with all his initials, which he thenceforth used. The Academy had been quick to recognize Turner’s genius, and he was always its faithful, conservative, and zealous friend. As an auditor, councillor, or a visitor he was scrupulous, and he attended general meetings and formal dinners with the same promptitude and certainty with which for forty-five years he sent his pictures to the annual exhibitions. He was a peacemaker in debates, but in business he was irresolute. In 1802 he visited the Continent for the first time, travelling in France, Switzerland, and Italy, and everywhere making sketches. At this time he carried sketch-books in which he jotted everything—all manner of drawings and outlines of nature and architecture, notes of local gossip, chemical memoranda, notes of expenses, tavern bills, views of coasts and cities, ruins, castles, manufacturing works, and detached figures. One book gives views about the Simplon Pass, another the sea-coast from Nice to Genoa, another contains countless jottings from the pictures in the Vatican, another is taken up with views in Paris and Rouen, and several are devoted to Scottish scenery.

In 1806 Turner began his Liber Studiorum, in rivalship of Claude’s Liber Veritatis; it was issued in parts in dark blue covers, each part containing five plates. It was discontinued in 1814, after seventy plates had been issued. Although not remunerative at the time, in later days as high as three thousand pounds has been paid for a single copy of the Liber, while the subscription price was only seventeen pounds ten shillings; even before Turner died a copy of it was worth over thirty guineas. Charles Turner, the engraver, used the proofs for kindling-paper; but some years later Colnaghi, the print dealer, paid him fifteen hundred pounds for his remaining “rubbish,” as he considered it. “Good God!” cried the old engraver; “I have been burning bank-notes all my life!” In 1878 Professor Norton, of Harvard University, published a set of thirty-three of the best of the Liber studies, reproduced in Boston by the heliotype process. The Liber Studiorum was intended to manifest Turner’s command of the whole compass of the landscape art, and was divided into six heads: historical, pastoral, elegant pastoral, mountain, marine, and architectural.

In 1808 Turner was appointed Professor of Perspective in the Royal Academy. During two or three years only, out of the thirty in which he held the professorship, did he deliver lectures. He spoke in a deep and mumbling voice, was confused and tedious in manner, and frequently became hopelessly entangled in blind mazes of obscure words. Sometimes when he had written out his lectures he was unable to read them. Once, after fumbling in his pockets, he exclaimed: “Gentlemen, I’ve been and left my lecture in the hackney-coach.” Still he was interested in this work, and Ruskin says: “The zealous care with which Turner endeavored to do his duty is proved by a large existing series of drawings, exquisitely tinted, and often completely colored, all by his own hand, of the most difficult perspective subjects—illustrating not only directions of light, but effects of light, with a care and completion which would put the work of any ordinary teacher to utter shame.” During this year he took a house at Hammersmith, Upper Mall, the garden of which ran down to the Thames, but still retained his residence in Harley Street. In 1812 he first occupied the house No. 47 Queen Anne Street, and this house he retained for forty years. It was dull, dingy, unpainted, weather-beaten, sooty, with unwashed windows and shaky doors, and seemed the very abode of poverty, and yet when Turner died his estate was sworn as under one hundred and forty thousand pounds—seven hundred thousand dollars. When Turner’s father died in 1830 he was succeeded by a withered and sluttish old woman named Danby. The whole house was dreary, dirty, damp, and full of litter. The master had a fancy for tailless—Manx—cats, and these made their beds everywhere without disturbance. In the gallery were thirty thousand fine proofs of engravings piled up and rotting. His studio had a fair north light from two windows, and was surrounded by water-color drawings. His sherry-bottle was kept in an old second-hand buffet.

About 1813 or 1814 Turner purchased a place at Twickenham; he rebuilt the house, and called it Solus Lodge. The rooms were small, and contained models of rigged ships which he used in his marine views; in his jungle-like garden he grew aquatic plants which he often copied in foregrounds. He kept a boat for fishing and marine sketching; also a gig and an old cropped-eared horse, with which he made sketching excursions. He made at this time the acquaintance of Rev. Mr. Trimmer, the rector of the church at Heston, who was a lover of art, and often took journeys with Turner. While visiting at the rectory Turner regularly attended church in proper form; and finally he wrote a note to Mr. Trimmer, alluding to his affection for one of the rector’s kinswomen, and suggesting: “If Miss —— would but waive bashfulness, or in other words make an offer instead of expecting one, the same [Lodge] might change occupiers.” But Turner was doomed to disappointment, and never made another attempt at matrimony. In 1814 Turner commenced his contributions of drawings to illustrate “Cook’s Southern Coast,” and continued this congenial work for twelve years, making forty drawings at the rate of about twenty guineas each; the drawings were returned to the artist after being engraved. In 1815 he exhibited the “Dido Building Carthage,” and in 1817 a companion picture, the “Decline of the Carthaginian Empire,” and for these two pictures the artist refused five thousand pounds, having secretly willed them to the National Gallery.

Ruskin divides Turner’s art life into three periods: that of study, from 1800 to 1820; that of working out art theories toward an ideal, from 1820 to 1835; and that of recording his own impressions of nature, from 1835 to 1845, preceded by a period of development, and followed by a period of decline, from 1845 to 1850. Besides his pictures painted on private commission, Turner exhibited two hundred and seventy-five pictures at the Academy. The “Rivers of England” was published in 1824, with sixteen engravings after Turner; another series contained six illustrations of the “Ports of England”—second-class cities. In 1826 the “Provincial Antiquities of Scotland” was published, with thirteen illustrations by Turner. The same year he sold his house at Twickenham, because, he said, “Dad” was always working in the garden, and catching abominable colds. In 1827 Turner commenced the “England and Wales” on his own account, and continued it for eleven years. It consisted of a hundred plates, illustrating ports, castles, abbeys, cathedrals, palaces, coast views, and lakes. In 1828 Turner went to Rome by way of Nismes, Avignon, Marseilles, Nice, and Genoa; and this year painted his “Ulysses Dividing Polyphemus,” of which Thornbury says: “For color, for life and shade, for composition, this seems to me to be the most wonderful and admirable of Turner’s realisms.” Ruskin calls it his central picture, illustrating his perfect power.

Of Turner’s wonderful versatility, Ruskin says: “There is architecture, including a large number of formal ‘gentlemen’s seats;’ then lowland pastoral scenery of every kind, including nearly all farming operations, plowing, harrowing, hedging and ditching, felling trees, sheep-washing, and I know not what else; there are all kinds of town life, court-yards of inns, starting of mail coaches, interiors of shops, house-buildings, fairs, and elections; then all kinds of inner domestic life, interiors of rooms, studies of costumes, of still-life and heraldry, including multitudes of symbolical vignettes; then marine scenery of every kind, full of local incident—every kind of boat, and the methods of fishing for particular fish being specifically drawn—round the whole coast of England; pilchard-fishing at St. Ives, whiting-fishing at Margate, herring at Loch Fyne, and all kinds of shipping, including studies of every separate part of the vessels, and many marine battle-pieces; then all kinds of mountain scenery, some idealized into compositions, others of definite localities, together with classical compositions; Romes and Carthages, and such others by the myriad, with mythological, historical, or allegorical figures; nymphs, monsters, and spectres, heroes and divinities.... Throughout the whole period with which we are at present concerned, Turner appears as a man of sympathy absolutely infinite—a sympathy so all-embracing that I know nothing but that of Shakespeare comparable with it. A soldier’s wife resting by the roadside is not beneath it; Rizpah watching the dead bodies of her sons, not above it. Nothing can possibly be so mean as that it will not interest his whole mind and carry his whole heart; nothing so great or solemn but that he can raise himself into harmony with it; and it is impossible to prophesy of him at any moment whether the next he will be in laughter or tears.”

In 1832 Turner made a will in which he bequeathed the bulk of his estate for the founding of an institution “for the Maintenance and Support of Poor and Decayed Male Artists being born in England and of English parents only, and of lawful issue.” It was to be called “Turner’s Gift,” and for the next twenty years the artist pinched, and economized to increase the fund for his noble purpose. At this time he was entering upon his third manner—that of his highest excellence, when he “went to the cataract for its iris, and the conflagration for its flames; asked of the sky its intensest azure, of the sun its clearest gold.” It is remarked by Ruskin, who has made most profound study of Turner’s works, that he had an underlying meaning or moral in his groups of foreign pictures; in Carthage, he illustrated the danger of the pursuit of wealth; in Rome, the fate of unbridled ambition; and in Venice, the vanity of pleasure and luxury. The Venetian pictures began in 1833, with a painting of the Doge’s Palace, Dogana, Campanile, and Bridge of Sighs; and with these were exhibited “Van Tromp Returning from Battle,” the “Rotterdam Ferry-boat,” and the “Mouth of the Seine.” In 1830 or 1831 he made, on commission from the publisher Cadell, twenty-four sketches to illustrate Walter Scott’s poems—published in 1834—and while doing this he was entertained royally at Abbotsford, and made excursions with Scott and Lockhart to Dryburgh Abbey and other points of interest. He went as far north as the Isle of Skye, where he drew Loch Corriskin, and nearly lost his life by a fall. About this time he made a series of illustrations for Scott’s “Life of Napoleon.” Turner spent some time in Edinburgh, frequently sketching with Thomson, a clergyman and local artist, who was preferred by some of the Scotch amateurs to Turner. He one day called at Thomson’s house to examine his paintings, but instead of expected praises he merely remarked, “You beat me in frames.” Turner made thirty-three illustrations for Rogers’s “Poems” (Fig. 75), and seventeen for an extended edition of Byron. He was in the habit at this time of frequently walking to Cowley Hall, the residence of a Mr. Rose, where he was kindly welcomed. He was there called “Old Pogey.” One day Mrs. Rose asked him to paint her favorite spaniel; in amazement he cried, “My dear madam, you do not know what you ask;” and always after this the lady went by the title of “My dear madam.” Mr. Rose tells how he and Turner sat up one night until two o’clock drinking cognac and water, and talking of their travels. When Mrs. Rose and a lady, a friend, visited Turner in a house in Harley Street, in mid-winter, they were entertained with wine and biscuits in a cold room, without a fire, where they saw seven tailless cats, which Turner said were brought from the Isle of Man.

Fig. 75.—Illustration from Rogers’s Poems.

Fig. 75.—Illustration from Rogers’s Poems.For three years Turner travelled in France, and made studies and sketches up and down its rivers. These were first published as “Turner’s Annual Tour,” but were afterward brought out by Bohn as “Liber Fluviorum.” These sketches have been highly praised by Ruskin; but Hammerton, who certainly knows French scenery far more accurately than Ruskin, while praising the exquisite beauty of Turner’s work, challenges its accuracy, and especially as to color, saying that “Turner, as a colorist, was splendid and powerful, but utterly unfaithful.” Leitch Ritchie, who was associated with Turner in this work, could not travel with him, their tastes were so unlike; and he says that Turner’s drawings were marvellously exaggerated, that he would make a splendid picture of a place without a single correct detail, trebling the height of spires and throwing in imaginary accessories. Turner always claimed the right to change the groupings of his landscapes and architecture at will, preferring to give a general and idealized view of the landscape rather than a precise copy thereof.

In 1835 he exhibited “Heidelberg Castle in the Olden Time,” “Ehrenbreitstein,” “Venice from the Salute Church,” and “Line-fishing off Hastings.” In 1836 he exhibited a “View of Rome from the Aventine Hill,” and the “Burning of the House of Lords and Commons,” which last was almost entirely painted on the walls of the exhibition. At this time it was the custom to have what were called “varnishing days” at the exhibition, during which time artists retouched, and finished up their pictures. They were periods of fun and practical jokes, and Turner always enjoyed, and made the most of them. He frequently sent his canvas to the Academy merely sketched out and grounded, and then coming in as early as four in the morning on varnishing days, he would put his nose to the sketch and work steadily with thousands of imperceptible touches until nightfall, while his picture would begin to glow as by magic. About this time he exhibited many pictures founded on classical subjects, or with the scenes laid in Italy or Greece, as “Apollo and Daphne in the Vale of Tempe,” “Regulus Leaving Rome to Return to Carthage,” the “Parting of Hero and Leander,” “Phryne Going to the Public Baths as Venus,” the “Banishment of Ovid from Rome, with Views of the Bridge and Castle of St. Angelo.” A year later he exhibited pictures of “Ancient Rome,” a vast dreamy pile of palaces, and “Modern Rome,” with a view of the “Forum in Ruins.”

One of the most celebrated of Turner’s pictures was that of the “Old Téméraire,” an old and famous line-of-battle ship, which in the battle of Trafalgar ran in between and captured the French frigates Redoubtable and Fougueux. Turner saw the Téméraire in the Thames after she had become old, and was condemned to be dismantled. The scene is laid at sunset, when the smouldering, red light is vividly reflected on the river, and contrasts with the quiet, gray and pearly tints about the low-hung moon. The majestic old ship looms up through these changing lights, bathed in splendor. The artist refused a large price for this picture by Mr. Lennox, of New York, and finally bequeathed it to the nation. In 1840 Turner exhibited the “Bacchus and Ariadne,” two marine scenes, and two views in Venice; also the well-known “Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, a Typhoon Coming On” (Fig. 76), which is now in the Museum of Fine Arts of Boston. Of this picture Thackeray says: “I don’t know whether it is sublime or ridiculous.” But Ruskin, in “Modern Painters,” says: “I believe if I were reduced to test Turner’s immortality upon any single work, I should choose the ‘Slave Ship.’ Its daring conception, ideal in the highest sense of the word, is based on the purest truth, and wrought out with the concentrated knowledge of a life. Its color is absolutely perfect, not one false or morbid hue in any part or line, and so modulated that every square inch of canvas is a perfect composition; its drawing as accurate as fearless; the ship buoyant, bending, and full of motion; its tones as true as they are wonderful; and the whole picture dedicated to the most sublime of subjects and impressions (completing thus the perfect system of all truth which we have shown to be formed by Turner’s works), the power, majesty, and deathfulness of the open, deep, illimitable sea.”

Fig. 76.—The Slave Ship. By Turner.

Fig. 76.—The Slave Ship. By Turner.No painter of modern times, or perhaps of any time, has ever provoked the discussion of his merits which Turner did. When he was at his best his great merits and his originality procured for him the strongest defenders, and finally brought his pictures into favor with the wealthy middle class of England, so that he obtained high prices, and since his death these prices have doubled, and even quadrupled. At a sale of Mr. Bicknell’s collection in 1836, ten of Turner’s pictures, which had been bought for three thousand seven hundred and forty-nine pounds, were sold for seventeen thousand and ninety-four pounds. As Turner grew older and his manner deteriorated he was assailed by the wits, the art critics, and the amateurs with cruel badinage, and to these censures Turner was morbidly sensitive. But even Ruskin admits that the pictures of his last five years are of “wholly inferior value,” with unsatisfactory foliage, chalky faces, and general indications of feebleness of hand.

Wornum, in his Epochs of Painting, said: “In the last ten years of his career, and occasionally before, Turner was extravagant to an extreme degree; he played equally with nature and with his colors. Light, with all its prismatic varieties, seems to have been the chief object of his studies; individuality of form or color he was wholly indifferent to. The looseness of execution in his latest works has not even the apology of having been attempted on scientific principles; he did not work upon a particular point of a picture as a focus and leave the rest obscure, as a foil to enhance it, on a principle of unity; on the contrary, all is equally obscure and wild alike. These last productions are a calamity to his reputation; yet we may, perhaps, safely assert that since Rembrandt there has been no painter of such originality and power as Turner.” Dr. Waagen says in his Treasury of Art in Great Britain: “No landscape painter has yet appeared with such versatility of talent. His historical landscapes exhibit the most exquisite feeling for beauty of hues and effect of lighting, at the same time that he has the power of making them express the most varied moods of nature.”

Toward the last part of his life Turner’s peculiarities increased; he became more morose, more jealous. He was always unwilling to have even his most intimate friends visit his studio, but he finally withdrew from his own house and home. Of late years he had frequently left his house for months at a time, and secreted himself in some distant quarter, taking care that he should not be followed or known. When the great Exhibition of 1851 opened, Turner left orders with his housekeeper that no one should be admitted to see his pictures. For twenty years the rain had been streaming in upon them through the leaky roof, and many were hopelessly ruined. He sent no pictures to the exhibition of that year, and he was hardly to be recognized when he appeared in the gallery. Finally his prolonged absence from the Academy meetings alarmed his friends; but no one dared seek him out. His housekeeper alone, of all that had known him, had the interest to hunt up the old artist. Taking a hint from a letter in one of his coats, she went to Chelsea, and, after careful search, found his hiding-place, with but one more day of life in him. It is said that, feeling the need of purer air than that of Queen Anne Street, he went out to Chelsea and found an eligible, little cottage by the side of the river, with a railed-in roof whence he could observe the sky. The landlady demanded references from the shabby, old man, when he testily replied, “My good woman, I’ll buy the house outright.” She then demanded his name—“in case, sir, any gentleman should call, you know.” “Name?” said he, “what’s your name?” “My name is Mrs. Booth.” “Then I am Mr. Booth.” And so he was known, the boys along the river-side calling him “Puggy Booth,” and the tradesmen “Admiral Booth,” the theory being that he was an old admiral in reduced circumstances. In a low studded, attic room, poorly furnished, with a single roof window, the great artist was found in his mortal sickness. He sent for his favorite doctor from Margate, who frankly told him that death was at hand. “Go down stairs,” exclaimed Turner, “take a glass of sherry, and then look at me again.” But no stimulant could change the verdict of the physician. An hour before he died he was wheeled to the window for a last look at the Thames, bathed in sunshine and dotted with sails. Up to the last sickness the lonely, old man rose at daybreak to watch, from the roof of the cottage, the sun rise and the purple flush of the coming day. The funeral, from the house in Queen Anne Street, was imposing, with a long line of carriages, and conducted with the ritual of the English Church in St. Paul’s Cathedral. Dean Milman read the service, and at its conclusion the coffin was borne to the catacombs, and placed between the tombs of James Barry and Sir Joshua Reynolds. Turner’s will, with its codicils, was so confused and vague that the lawyers fought it in the courts for four years, and it was finally settled by compromise. The real estate went to the heir-at-law, the pictures and drawings to the National Gallery, one thousand pounds for a monument in St. Paul’s Cathedral, and twenty thousand pounds to the Royal Academy for annuities to poor artists. Turner’s gift to the British nation included ninety-eight finished paintings and two hundred and seventy pictures in various stages of progress. Ruskin, while arranging and classifying Turner’s drawings, found more than nineteen thousand sketches and fragments by the master’s hand, some covered with the dust of thirty years.

Sir David Wilkie (1785-1841) has been called the “prince of British genre painters.” His father was a minister, and David was placed in the Trustees’ Academy in Edinburgh in 1799. In 1805 he entered the Royal Academy in London, and was much noticed on account of his “Village Politicians,” exhibited the next year. From this time his fame and popularity were established, and each new work was simply a new triumph for him. The “Card Players,” “Rent Day,” the “Village Festival,” and others were rapidly painted and exhibited.

In 1825 Wilkie went to the Continent, and remained three years. He visited France, Germany, Italy, and Spain, and after his return he painted a new class of subjects in a new manner. He made many portraits, and his other works were historical subjects. His most celebrated works in this second manner were “John Knox Preaching,” “Napoleon and the Pope at Fontainebleau,” and “Peep-o’-Day Boy’s Cabin.” The portrait of the landscape painter William Daniell is a good picture.

In 1830 Wilkie succeeded Sir Thomas Lawrence as painter to the king, as he had been limner to the King of Scotland since 1822. He was not knighted until 1836. In 1840 he visited Constantinople, and made a portrait of the sultan; he went then to the Holy Land and Egypt. While at Alexandria, on his way home, Wilkie complained of illness, and on shipboard, off Gibraltar, he died, and was buried at sea. This burial is the subject of one of Turner’s pictures, and is now in the National Gallery.

The name of Landseer is an important one in British art. John Landseer (1761-1852) was an eminent engraver; his son Thomas (1795-1880) followed the profession of his father and arrived at great celebrity in it. Charles, born in 1799, another son of John Landseer, became a painter and devoted himself to a sort of historical genre line of subjects, such as “Cromwell at the House of Sir Walter Stewart in 1651,” “Surrender of Arundel Castle in 1643,” and various others of a like nature. Charles Landseer travelled in Portugal and Brazil when a young man; he was made a member of the Royal Academy in 1845; from 1851 to 1871 he was keeper of the Academy, and has been an industrious and respected artist. But the great genius of the family was:

Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-1873), the youngest son of John Landseer, the engraver. He received his first drawing lessons from his father, and from a very early age showed a great talent for sketching and that love for the brute creation which have been his chief characteristics as an artist. He had the power to understand his dumb subjects as well as if they spoke some language together, and then he had the ability to fix the meaning of all they had told him upon his canvas, by means of the sketching lines which gave the precise form of it all and by his finishing shades which put in the expression. If his animals were prosperous and gladsome, he represented their good fortune with hearty pleasure; if they were suffering, sad, or bereaved, he painted their woes with a sympathy such as none but a true friend can give.

When Edwin and Thomas were old enough that their father thought other instruction than his own should be given them, he placed them with Haydon, and in these early days the master predicted that Edwin Landseer would be the Snyders of England. Edwin sent his first picture to the Royal Academy when he was but thirteen years old, and during the following fifty-eight years there were but six exhibitions to which he did not contribute. When he began his studies at the Royal Academy he was fourteen years old, and already famous as an animal painter. He was a bright, curly-headed, manly lad, and the aged Fuseli, then keeper of the Academy, grew to be very fond of him; he would often ask, “Where is my little dog-boy?”

Edwin Landseer now worked on diligently and quietly; his works were constantly praised, and he received all the patronage that he desired. Through the advice of his master, Haydon, he had the habit of dissecting animals, and learning their anatomy with all the exactness with which other artists study that of human beings. About 1820 a lion died in the Exeter Change Menagerie, and Edwin Landseer secured the body for dissection. He then painted three large pictures of lions, and during the year in which he became eighteen years old, he exhibited these pictures and others of horses, dogs, donkeys, deer, goats, wolves, and vultures.

When nineteen, in 1821, he painted “Pointers, To-ho!” a hunting scene, which was sold in 1872, the year before his death, for two thousand and sixteen pounds. In 1822 Landseer gained the prize of the British Institution, one hundred and fifty pounds, by his picture of “The Larder Invaded.” He made the first sketch for this on a child’s slate, which is still preserved as a treasure. But the most famous of this master’s early works is the “Cat’s Paw,” in which a monkey uses a cat’s paw to draw chestnuts from a hot stove. Landseer was paid one hundred pounds; its present value is three thousand pounds, and it is kept at the seat of the Earl of Essex, Cashiobury.

This picture of the “Cat’s Paw” had an important result for the young artist, as it happened that it was exhibited when Sir Walter Scott was in London, and he was so much pleased with it that he made Landseer’s acquaintance, and invited him to visit Abbotsford. Accordingly, in 1824, Landseer visited Sir Walter in company with Leslie, who then painted a portrait of the great novelist, which now belongs to the Ticknor family of Boston. It was at this time that Sir Walter wrote in his journal: “Landseer’s dogs were the most magnificent things I ever saw, leaping, and bounding, and grinning all over the canvas.” Out of this visit came a picture called “A Scene at Abbotsford,” in which the dog Maida, so loved by Scott, was the prominent figure; six weeks after it was finished the dog died.

At this time Sir Walter was not known as the author of the “Waverley Novels,” but in later years Landseer painted a picture which he called “Extract from a Journal whilst at Abbotsford,” to which the following was attached: “Found the great poet in his study, laughing at a collie dog playing with Maida, his favorite old greyhound, given him by Glengarry, and quoting Shakespeare—‘Crabbed old age and youth cannot agree.’ On the floor was the cover of a proof-sheet, sent for correction by Constable, of the novel then in progress. N. B.—This took place before he was the acknowledged author of the ‘Waverley Novels.’” Landseer early suspected Scott of the authorship of the novels, and without doubt he came to this conclusion from what he saw at Abbotsford.