Spanish painting had its birth during the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella, and may be said to have been derived from Italy, through the influence of the Italian painters who went to Spain, and the Spanish artists who made their studies in Italy. But in spite of this strong Italian influence Spanish painting has its own characteristics which separate it from all other schools, and give it a high position on its own merits.Antonio del Rincon (1446-1500) was the first Spanish painter of whom we know. If any works of his remain they are portraits of his august sovereigns now in the Cathedral of Granada; but it is probable that these pictures are copies of the originals by Rincon.

Dating the beginning of the Spanish school from the last half of the fifteenth century, it is the third school in Europe as to age, it being about two centuries later than the Italian, and one century later than the Flemish school. Its importance is only exceeded by that of Italy. The distinguishing feature of Spanish art is its gravity, or we may almost say its strictly religious character, for, excepting portraits, there were few pictures of consequence that had not a religious meaning. Some artists were also priests, and, as the officers of the Inquisition appointed inspectors whose duty it was to report for punishment any artist who did not follow the rules of the Inquisition, it is easy to understand that the painters were careful to keep within the rules fixed for them. Whatever flights of imagination one might have in secret, he would scarcely run the risk of being excommunicated from the church, sent into exile for a year, and fined one thousand five hundred ducats for the pleasure of putting his fancies on canvas.

Pacheco, who was an inspector at Seville, published minute rules for the representation of sacred subjects and persons, and other writers did the same. There was a long and grave discussion over the propriety of painting the devil with horns and a tail. It was decided that he should have horns because, according to the legend of St. Theresa, he had horns when he appeared to that saint; and he was allowed to have a tail because it was thought to be a suitable appendage to a fallen angel who had lost his wings. One very strict rule was that the feet of the Virgin Mary should be covered, and nude figures or portions of the figure were strictly forbidden.

Another important influence upon the Spanish artists was their belief that the Virgin Mary and other holy spirits appeared to inspire them and aid them in painting their pictures. In fact, the church was the chief patron of art, and the artist was one of her most valuable teachers. A learned Spanish writer said: “For the ignorant, what master is like painting? They may read their duty in a picture though they may not search for it in books.”

The painters of Spain were divided between the schools of Castile, Seville, and Valencia. That of Castile was founded at Toledo early in the fifteenth century, and was maintained about two hundred years. Claudio Coello was of this school; he died in 1693, and has well been called “the last of the old masters of Spain.”

Alonzo Berreguette (1480-1561), born at Parades de Nava, in Castile, was the most eminent Spanish artist of his time. He is called the Michael Angelo of Spain, because he was painter, sculptor, and architect. He was painter to Philip I. Later he went to Italy, and journeyed from Florence to Rome with Michael Angelo in 1505. He studied in Italy many years. He was appointed painter and sculptor to the Emperor Charles V. Berreguette received four thousand four hundred ducats for the altar in the Church of St. Benito el Real in Valladolid, where he settled. When he was almost eighty years old he went to Toledo to erect a monument in the Hospital of St. John Baptist. He was lodged in the hospital, and died there. He left a large fortune, and was buried with splendid ceremonies at the expense of the emperor.

Luis de Morales (1510-1586) was called “the divine.” He belonged to the school of Castile, and very little is known of his early life. When he was fifty-five years old Philip II. invited him to court. When Morales appeared he was so splendidly dressed that the king was angry, and gave orders that he should be paid a certain sum and dismissed. But the poor painter explained that he had spent all that he had in order to come before the king in a dress befitting Philip’s dignity. Then Philip pardoned him, and allowed him to paint one picture; but as this was not hung in the Escorial, Morales was overcome by mortification, and almost forsook his painting, and fell into great poverty. In 1581 the king saw Morales at Badajoz, in a very different dress from that he had worn at court. The king said: “Morales, you are very old.” “Yes, sire, and very poor,” replied the painter. The king then commanded that he should have two hundred ducats a year from the crown rents with which to buy his dinners. Morales hearing this, exclaimed, “And for supper, sire?” This pleased Philip, and he added one hundred ducats to the pension. The street in Badajoz on which Morales lived bears his name.

Nearly all his pictures were of religious subjects, and on this account he was called “the divine.” He avoided ghastly, painful pictures, and was one of the most spiritual of the artists of Spain. Very few of his pictures are seen out of Spain, and they are rare even there. His masterpiece is “Christ Crowned with Thorns,” in the Queen of Spain’s Gallery at Madrid. In the Louvre is his “Christ Bearing the Cross.” At the sale of the Soult collection his “Way to Calvary” sold for nine hundred and eighty pounds sterling.

Alonso Sanchez Coello (about 1515-1590) was the first great portrait painter of Spain. He was painter-in-ordinary to Philip II., and that monarch was so fond of him that in his letters he called him “my beloved son.” At Madrid the king had a key to a private entrance to the apartments of Coello, so that he could surprise the painter in his studio, and at times even entered the family rooms of the artist. Coello never abused the confidence of Philip, and was a favorite of the court as well as of the monarch. Among his friends were the Popes Gregory XIII. and Sixtus V., the Cardinal Alexander Farnese, and the Dukes of Florence and Savoy. Many noble and even royal persons were accustomed to visit him and accept his hospitality. He was obliged to live in style becoming his position, and yet when he died he left a fortune of fifty-five thousand ducats. He had lived in Lisbon, and Philip sometimes called him his “Portuguese Titian.”

Very few of his portraits remain; they are graceful in pose and fine in color. He knew how to represent the repose and refinement of “gentle blood and delicate nurture.” Many of his works were burned in the Prado. His “Marriage of St. Catherine” is in the Gallery of Madrid. A “St. Sebastian” painted for the Church of St. Jerome, at Madrid, is considered his masterpiece. Lope de Vega wrote Coello’s epitaph, and called his pictures

“Eternal scenes of history divine,

Wherein for aye his memory shall shine.”

Juan Fernandez Navarrete (1526-1579), called El Mudo, because deaf and dumb, is a very interesting painter. He was not born a mute, but became deaf at three years of age, and could not learn to speak. He studied some years in Italy, and was in the school of Titian. In 1568 he was appointed painter to Philip II. His principal works were eight pictures for the Escorial, three of which were burned. His picture of the “Nativity” is celebrated for its lights, of which there are three; one is from the Divine Babe, a second from the glory above, and a third from a torch in the hand of St. Joseph. The group of shepherds is the best part of the picture, and when Tibaldi saw the picture he exclaimed, “O! gli belli pastori!” and it has since been known as the “Beautiful Shepherds.”

His picture of “Abraham and the Three Angels” was placed near the door where the monks of the Escorial received strangers. The pictures of Navarrete are rare. After his death Lope de Vega wrote a lament for him, in which he said,

“No countenance he painted that was dumb.”

When the “Last Supper” painted by Titian reached the Escorial, it was found to be too large for the space it was to occupy in the refectory. The king ordered it to be cut, which so distressed El Mudo that he offered to copy it in six months, in reduced size, and to forfeit his head if he did not fulfil his promise. He also added that he should hope to be knighted if he copied in six months what Titian had taken seven years to paint. But Philip was resolute, and the picture was cut, to the intense grief of the dumb Navarrete. While the painter lived Philip did not fully appreciate him; but after his death the king often declared that his Italian artists could not equal his mute Spaniard.

Juan Carreño de Miranda (1614-1685) is commonly called Carreño. He was of an ancient noble family. His earliest works were for the churches and convents of Madrid, and he acquired so good a name that before the death of Philip IV. he was appointed one of his court-painters. In 1671 the young king Charles gave Carreño the cross of Santiago, and to his office of court-painter added that of Deputy Aposentador. He would allow no other artist to paint his likeness unless Carreño consented to it. The pictures of Carreño were most excellent, and his character was such as to merit all his good fortune. His death was sincerely mourned by all who knew him.

It is said that on one occasion he was in a house where a copy of Titian’s “St. Margaret” hung upon the wall, and those present united in saying that it was abominably done. Carreño said: “It has at least one merit; it shows that no one need despair of improving in art, for I painted it myself when I was a beginner.”

Gregorio Utande, a poor artist, had painted a “Martyrdom of St. Andrew” for the nuns of Alcalà, and demanded one hundred ducats for it. The nuns thought the price too much, and wished to have Carreño value the work. Utande took the picture to Carreño, and first presenting the great master with a jar of honey, asked him to touch up his St. Andrew for him. Carreño consented, and, in fact, almost repainted Utande’s picture. A short time after Carreño was asked to value the St. Andrew, but declined. Then Herrera valued it at two hundred ducats, which price the nuns paid. After Utande received his money he told the whole story, and the picture was then known as “La Cantarilla de Miel,” or “the pot of honey.”

Claudio Coello (1635-1693), who, as we have said, has been called the last of the old Spanish masters, was intended by his father for his own profession, that of bronze-casting. But Claudio persuaded his father to allow him to study painting, and before the close of his life he became the most famous painter in Madrid. He was not only the court-painter, but also the painter to the Cathedral of Toledo and keeper of the royal galleries. It was not strange that he should feel that he merited the honor of painting the walls of the Escorial, and when this was refused him and Luca Giordano was selected for the work, Coello threw aside his brushes and paints, grew sad, then ill, and died a year later. His masterpiece is now in the Escorial; it represents the “Collocation of the Host.” His own portrait painted by himself is in the gallery of the Hermitage at St. Petersburg.

The school of Seville was the most important school of Spain. It is also known as the school of Andalusia. It dates from the middle of the fifteenth century, and its latest master, Alonso Miguel de Tobar, died in 1758.

Luis de Vargas (1502-1568), one of the earliest of the painters of the school of Seville, was a devout and holy man. He was accustomed to do penance, and in his room after his death scourges were found with which he had beaten himself, and a coffin in which he had been accustomed to lie and meditate upon death and a future life. It is said that Vargas studied twenty-eight years in Italy. His pictures were fine. His female heads were graceful and pure, his color good, and the whole effect that of grand simplicity. His picture of the “Temporal Generation of Our Lord” is his best work in Seville. Adam is kneeling in the foreground, and his leg is so well painted that the picture has been called “La Gamba.” In spite of his seriousness Vargas was a witty man. On one occasion he was asked to give his opinion of a very poor picture of “Christ on the Cross.” Vargas replied: “He looks as if he were saying, ‘Forgive them, Lord, for they know not what they do!’”

Pablo de Cespedes (1538-1608) was born at Cordova, and is an important person in the history of his time, for he was a divine, a poet, and a scholar, as well as an architect, sculptor, and painter. He was a graduate of the University of Alcalà, and excelled in Oriental languages. He studied art in Rome, and while there made a head of Seneca in marble, and fitted it to an antique trunk; on account of this work he was called “Victor il Spagnuolo.” Zuccaro was asked to paint a picture for the splendid Cathedral of Cordova; he declined, and said that while Cespedes was in Spain they had no need of Italian artists. The pictures of Cespedes which now remain are so faded and injured that a good judgment can scarcely be formed of them; but they do not seem to be as fine as they were thought to be in his day. His “Last Supper” is in the Cathedral of Cordova. In the foreground there are some jars and vases so well painted that visitors praised them. Cespedes was so mortified at this that he commanded his servant to rub them out, and only the most judicious admiration for the rest of the picture and earnest entreaty for the preservation of the jars saved them from destruction. He left many writings upon artistic subjects and an essay upon the antiquity of the Cathedral of Cordova. He was as modest as he was learned, and was much beloved. He was made a canon in the Cathedral of Cordova, and was received with “full approbation of the Cordovese bishop and chapter.”

Francisco Pacheco (1571-1654) was born at Seville. He was a writer on art, and is more famous as the master of Velasquez and on account of his books than for his pictures. He established a school where younger men than himself could have a thorough art education. Pacheco was the first in Spain to properly gild and paint statues and bas-reliefs. Some specimens of his work in this specialty still exist in Seville.

Francisco de Herrera, the elder (1576-1656), was a very original painter. He was born at Seville, and never studied out of Andalusia. He had so bad a temper that he drove his children and his pupils away from him. He knew how to engrave on bronze, and made false coins; when his forgery was discovered, he took refuge with the Jesuits. While in their convent Herrera painted the history of St. Hermengild, one of the patron saints of Seville. When Philip IV. saw his picture he forgave him his crime, and set him at liberty.

Francisco Zurbaran (1598-1662) was one of the first among Spanish painters. He was skilful in the use of colors, and knew how to use sober tints and give them a brilliant effect. He did not often paint the Madonna. His female saints are like portraits of the ladies of his day. He was very successful in painting animals, and his pictures of drapery and still-life were exact in their representation of the objects he used for models. He painted historical and religious pictures, portraits and animals; but his best pictures were of monks. Stirling says: “He studied the Spanish friar, and painted him with as high a relish as Titian painted the Venetian noble, and Vandyck the gentleman of England.”

Zurbaran was appointed painter to Philip IV. before he was thirty-five years old. He was a great favorite with Philip, who once called Zurbaran “the painter of the king, and king of painters.” Zurbaran’s finest works are in the Museum of Seville. He left many pictures, and the Louvre claims to have ninety-two of them in its gallery.

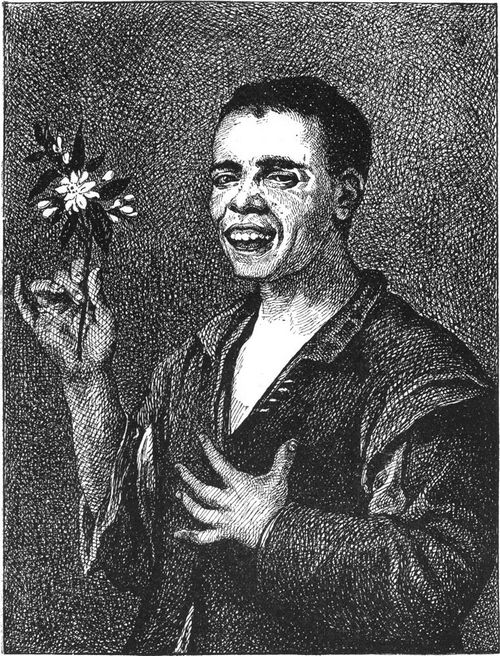

Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velasquez (1599-1660) was born at Seville, and died at Madrid. His parents were of noble families; his father was Juan Rodriguez de Silva, and his mother Geronima Velasquez, by whose name, according to the custom of Andalusia, he was called. His paternal grandfather was a Portuguese, but so poor that he was compelled to leave his own country, and seek his fortune at Seville, and to this circumstance Spain owes her greatest painter. Velasquez’s father became a lawyer, and lived in comfort, and his mother devoted herself to his education. The child’s great love of drawing induced his father to place young Velasquez in the school of Herrera, where the pupil acquired something of his free, bold style. But Velasquez soon became weary, and entered the school of Francisco Pacheco, an inferior painter, but a learned and polished gentleman. Here Velasquez soon learned that untiring industry and the study of nature were the surest guides to perfection for an artist. Until 1622 he painted pictures from careful studies of common life, and always with the model or subject before him—adhering strictly to form, color, and outline. He is said to have kept a peasant lad for a study, and from him executed a variety of heads in every posture and with every possible expression. This gave him wonderful skill in taking likenesses. To this period belong the “Water Carrier of Seville,” now at Apsley House, several pictures of beggars, and the “Adoration of the Shepherds,” now in the Louvre, where is also a “Beggar Boy munching a piece of Pastry.” At Vienna is a “Laughing Peasant” holding a flower (Fig. 64), and in Munich another “Beggar Boy.” In 1622 his strong desire to see the paintings in the Royal Galleries led him to Madrid. Letters which he carried gave him admission to the works of art; but excepting securing the friendship of Fonesca, a noted patron of art, and an order to paint a portrait of the poet Gongora, he was unnoticed, and so he returned in a few months to Seville. Subsequently Fonesca interested the minister Olivarez in his behalf. This resulted in a letter summoning Velasquez to court, with an enclosure of fifty ducats for the journey. He was attended by his slave, Juan Pareja, a mulatto lad, who was his faithful attendant for many years, and who became an excellent painter. His former instructor, Pacheco, now his father-in-law, also accompanied him. His first work at the capital, naturally, was a portrait of his friend Fonesca, which so pleased the king, Philip IV., that he appointed Velasquez to his service, in which he remained during his life. This gave him full opportunity to perfect himself, for the king was never weary of multiplying pictures of himself. Velasquez also painted many portraits of the other members of the royal family, in groups and singly. His life was even and prosperous, and he made steady advances toward perfection. He was sent to Italy to study and to visit the galleries and works in all the cities. A second time the king sent him to Italy to purchase works of art, with orders to buy anything he thought worth having. He was everywhere received with consideration and kindness. The pope sat to him for his portrait; the cardinals Barberini and Rospigliosi; the sculptors Bernini and Algardi; the painters Nicolas Poussin, Pietro da Cortona, Claude and Matteo Prete were his friends and associates. Upon his return to Madrid, Velasquez was appointed aposentador-major, with a yearly salary of three thousand ducats, and a key at his girdle to unlock every door in the palace. He superintended the ceremonies and festivals of the royal household; he arranged in the halls of the Alcazar the bronzes and marbles purchased in Italy; he also cast in bronze the models he brought from abroad, and he yet found time to paint his last great picture, “Las Meniñas,” or the “Maids of Honor,” which represents the royal family, with the artist, maids of honor, the dwarfs, and a sleeping hound. It is said that when the king saw the picture he declared but one thing was wanting, and with his own hand significantly painted the cross of Santiago upon the breast of the artist. When the courts of France and Spain met on the Isle of Pheasants for the betrothal of the Infanta Maria Teresa to Louis XIV., Velasquez superintended all the ceremonies and all the festivities. These were of surpassing splendor, for these two courts were at this time the most luxurious in Europe. Stirling says the fatigues of the life of Velasquez shortened his days. He arrived at Madrid on his return, on June 26th, and from that time was gradually sinking. He died August 6th. He was buried with magnificent ceremonies in the Church of San Juan. His wife survived him but eight days; she was buried in the same grave.

Fig. 64.—Laughing Peasant. Velasquez.

Fig. 64.—Laughing Peasant. Velasquez.

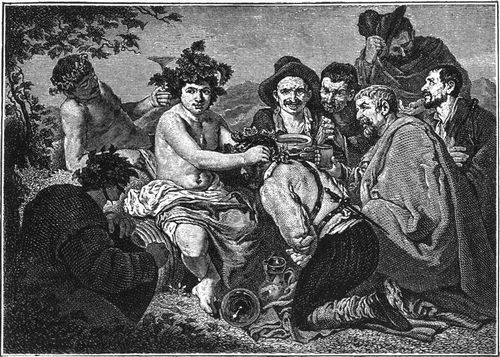

Fig. 65.—The Topers. By Velasquez.

Fig. 65.—The Topers. By Velasquez.The character of Velasquez was a rare combination of freedom from jealousy, power to conciliate, sweetness of temper, strength of will and intellect, and steadfastness of purpose. He was the friend of Rubens and of Ribera, the protector of Cano and Murillo, who succeeded and were, next to him, the greatest painters of Spain. As the favorite of Philip IV., in fact, his minister for artistic affairs, he filled his office with purity and disinterestedness.

Juan de Pareja (1610-1670) was born in Spanish South America. He was never a great artist; but the circumstances of his life make him interesting. He was the slave of Velasquez, and was employed as color-grinder. He studied painting secretly, and at last, on an occasion when the king visited the studio of his master, Pareja showed him a picture of his own painting, and throwing himself at Philip’s feet begged pardon for his audacity. Both Philip and Velasquez treated him very kindly. Velasquez gave Pareja his freedom; but it is said that he continued to serve his old master faithfully as long as he lived. Pareja succeeded best as a portrait painter. His works are not numerous, and are seen in few collections out of Spain.

Bartolomé Estéban Murillo (1618-1682) was born at Seville. His parents were Gaspar Estéban and Maria Perez, and the name of his maternal grandmother, Elvira Murillo, was added to his own, according to Andalusian custom. From childhood he showed his inclination for art, and although this at first suggested to his parents that he should be educated as a priest, the idea was soon abandoned, as it was found that his interest in the paintings which adorned the churches was artistic rather than religious. He was therefore, at an early age, placed in the studio of his maternal uncle, Juan de Castillo, one of the leaders of the school of art of Seville. Castillo was then about fifty years old, and had as a student with Louis Fernandez acquired the Florentine style of the sixteenth century—combining chaste designing with cold and hard coloring. Murillo was thus early instructed not only in grinding colors and in indispensable mechanical details, but was thoroughly grounded in the important elements of purity of conception and dignity of treatment and arrangement. Seville at this time was the richest city in the Spanish empire. Its commerce with all Europe, and especially with Spanish America, was at its height. The Guadalquivir was alive with its shipping. Its palaces of semi-Moorish origin were occupied by a wealthy and luxurious nobility. The vast cathedral had been finished a century before. The tower “La Giralda,” three hundred and forty feet in height, is to this day one of the greatest marvels in Christendom, and with its Saracenic ornament and its “lace work in stone” is beyond all compare. The royal palace of the Alcazar, designed by Moorish architects, rivalled the Alhambra, and was filled with the finest workmanship of Grenada. There were one hundred and forty churches, of which many had been mosques, and were laden with the exquisite ornaments of their original builders. Such a city was sure to stimulate artists and be their home. The poorer ones were in the habit of exposing their works on balconies, on the steps of churches or the cathedral, or in any place where they would attract attention. Thus it often happened on festival days that a good work would command fame for an artist, and gain for him the patronage of some cathedral chapter or generous nobleman. Castillo removed to Cadiz in 1640, and Murillo, who was very poor, could only bring himself before the public, and earn sufficient for the bare necessities of life by thus exposing his pictures in the market of the Feria, as it was called, in front of the Church of All Saints. He struggled along in this way for two years. Early in 1640, Murillo met with an old fellow-pupil, Moya, who had been campaigning in Flanders in the Spanish army, and had there become impressed with the worth of the clear and strong style of the Flemish masters. Especially was he pleased with Vandyck, so that he followed him to England, and there studied as his pupil during the last six months of Vandyck’s life. Moved by Moya’s romancing stories of travel, adventure, and study, Murillo resolved to see better pictures than were to be found at Seville, and, if possible, to visit Italy. As a first step he painted a quantity of banners, madonnas, flower-pieces—anything and everything—and sold them to a ship owner, who sent them to Spanish America; and it is said that this and similar trades originated the story that Murillo once visited Mexico and other Spanish-American countries. Thus equipped with funds, and without informing his friends (his parents were dead), he started on foot across the mountains and the equally dreaded plains for Madrid, which he entered at the age of twenty-five, friendless and poor. He sought out Velasquez, and asked him for letters to his friends in Rome. But Velasquez, then at the height of his fame and influence, was so much interested in the young enthusiast that he offered him lodgings and an opportunity to study and copy in the galleries of Madrid. The Royal Galleries contained carefully selected pictures from the Italian and Flemish schools, so that Murillo was at once placed in the very best possible conditions for success. Murillo thus spent more than two years, mostly under the direction of Velasquez, and worked early and late. He copied from the Italian and Flemish masters, and drew from casts and from life. This for a time so influenced his style that even now connoisseurs are said to discern reminiscences of Vandyck and Velasquez in the pictures painted by him on his first return to Seville. At the end of two years Velasquez advised Murillo to go to Rome, and offered to assist him. But Murillo decided first to return to Seville, and perhaps had come to the resolution not to go to Italy; but this may be doubted. He knew the progress he had made; he was reasonably certain that, if not the superior, he was the equal of any of the artists he had left behind in Seville. He was sure of the wealth, and taste, and love for art in his native city. His only sister was living there. The rich and noble lady he afterward married resided near there. And so we can hardly wonder that the artist gave up a cherished journey to Italy, and returned to the scene of his early struggles with poverty.

The first works which Murillo painted after his return were for the Franciscan Convent. They brought him little money but much fame. They were eleven in number, but even the names of some are lost. One represents St. Francis resting on his iron bed, listening in ecstacy to the notes of a violin which an angel is playing to him; another portrays St. Diego of Alcalá, asking a blessing on a kettle of broth he is about to give to a group of beggars clustered before him; another represents the death of St. Clara of Assisi, in the rapturous trance in which her soul passed away, surrounded by pale nuns and emaciated monks looking upward to a contrasting group of Christ and the Madonna, with a train of celestial virgins bearing her shining robe of immortality. The companion picture is a Franciscan monk who passes into a celestial ecstacy while cooking in the convent kitchen, and who is kneeling in the air, while angels perform his culinary tasks. These pictures brought Murillo into speedy notice. Artists and nobles flocked to see them. Orders for portraits and altar-pieces followed in rapid succession, and he was full of work. Notwithstanding the fact that he was acknowledged to be at the head of his profession in Seville, his style at this time was cold and hard. It is called frio (cold), to distinguish it from his later styles. The Franciscan Convent pictures were carried off by Marshal Soult, and fortunately; for the convent was burned in 1810. His second style, called calido, or warm, dated from about the time of his marriage, in 1648, to a lady of distinguished family, named Doña Beatriz de Cabrera y Sotomayor. She was possessed of considerable property, and had lived in the village of Pilas, a few leagues southwest of Seville. Her portrait is not known to exist; but several of Murillo’s madonnas which resemble each other are so evidently portraits, that the belief is these idealized faces were drawn from the countenance of the wife of the master.

His home now became famous for its hospitable reunions, and his social position, added to his artistic merits, procured for him orders beyond his utmost ability to fill. One after another in quick succession, large, grand works were sent out from his studio to be the pride of churches and convents. At this time his pictures were noted for a portrait-like naturalness in their faces, perhaps lacking in idealism, but withal pure and pleasing; the drapery graceful and well arranged, the lights skilfully disposed, the tints harmonious, and the contours soft. His flesh tints were heightened by dark gray backgrounds, so amazingly true that an admirer has said they were painted in blood and milk. The calido, or warm manner, was preserved for eight or ten years. In this style were painted an “Immaculate Conception,” for the Franciscan Convent; “The Nativity of the Virgin,” for the high altar of the Seville Cathedral; a “St. Anthony of Padua” for the same church, and very many others equally famous. In 1874 the St. Anthony was stolen from the cathedral, and for some time was unheard of, until two men offered to sell it for two hundred and fifty dollars to Mr. Schaus, the picture dealer in New York. He purchased the work and turned it over to the Spanish Consul, who immediately returned it to the Seville Cathedral, to the great joy of the Sevillians. In 1658 Murillo turned his attention to the founding of an Academy of Art, and, though he met with many obstacles, the institution was finally opened for instruction in 1660, and Murillo was its first president. At this time he was taking on his latest manner, called the vaporoso, or vapory, which was first used in some of his pictures executed for the Church of Sta. Maria la Blanca. In this manner the rigid outlines of his first style is gone; there is a feathery lightness of touch as if the brush had swept the canvas smoothly and with unbroken evenness: this softness is enhanced by frequent contrasts with harder and heavier groups in the same picture.

But the highest point in the art was reached by Murillo in the eleven pictures which he painted in the Hospital de la Caridad. Six of these are now in their original places; five were stolen by Soult and carried to France; some were returned to Spain, but not to the hospital.

The convent of the Capuchins at Seville at one time possessed twenty pictures by this master. The larger part of them are now in the Museum of Seville, and form the finest existing collection of his works. This museum was once a church, and the statue of Murillo is placed in front of it. Although the lighting of this museum is far inferior to that of Madrid and many others, yet here one must go to realize fully the glory of this master. Among the pictures is the “Virgen de la Sevilletá,” or Virgin of the Napkin. It is said that the cook of the convent had become the friend of the painter, and begged of him some memento of his good feeling; the artist had no canvas, and the cook gave him a napkin upon which this great work was done.

Fig. 66.—The Immaculate Conception. By Murillo.

Fig. 66.—The Immaculate Conception. By Murillo.Murillo’s representation of that extremely spiritual and mystical subject called the Immaculate Conception, has so far excelled that of any other artist that he has sometimes been called “the painter of the Conception.” His attention was especially called to this subject by the fact that the doctrine it sets forth was a pet with the clergy of Seville, who, when Pope Paul V., in 1617, published a bill making this doctrine obligatory, celebrated the occasion with all possible pomp in the churches; the nobles also gave entertainments, and the whole city was alive with a fervor of religious zeal and a desire to manifest its love for this dogma. The directions given by the Inspector of the Holy Office for the representation of this subject were extremely precise; but Murillo complied with them in general effect only, and disregarded details when it pleased him: for example, the rules prescribed the age of the Virgin to be from twelve to thirteen, and the hair to be of golden hue. Murillo sometimes pictured her as a dark-haired woman. It is said that when he painted the Virgin as very young his daughter Francesca was his model; later the daughter became a nun in the convent of the Madre de Dios.

The few portraits painted by Murillo are above all praise; his pictures of humble life, too, would of themselves have sufficed to make him famous. No Spanish artist, except Velasquez, has painted better landscapes than he. But so grand and vast were his religious works that his fame rests principally on them. It is true, however, that in England and in other countries out of Spain he was first made famous by his beggar boys and kindred subjects.

Murillo and Velasquez may be said to hold equivalent positions in the annals of Spanish Art—Murillo as the painter for the church, and Velasquez as that of the court. As a delineator of religious subjects Murillo ranked only a very little below the greatest Italian masters, and even beside them he excels in one direction; for he is able more generally and fully to arouse religious emotions and sympathies. This stamps his genius as that of the first order, and it should also be placed to his credit, in estimating his native talent, that he never saw anything of all the Classic Art which was such a source of inspiration to the artists of Italy. Stirling says: “All his ideas were of home growth: his mode of expression was purely national and Spanish; his model—nature, as it existed in and around Seville.”

While painting a marriage of St. Catherine for the Capuchin Church of Cadiz, Murillo fell from the scaffold, and soon died from his injuries: he was buried in the Church of Sta. Cruz, and it is a sad coincidence that this church and that of San Juan, at Madrid, in which Velasquez was interred, were both destroyed by the French under the command of Soult.

The character of Murillo was such as to command the greatest respect, and though he was not associated with as many royal personages as Velasquez, he was invited to court, and received many flattering acknowledgments of his genius. His fame was not confined to his own country, and his portrait was engraved in Flanders during the last year of his life. He had many strong personal friends, and his interest in the academy and his generosity to other artists prove him to have been above all mean jealousies: he loved Art because it was Art, and did all in his power for its elevation in his own country. It is probable that since his death more money has been paid for a single picture by him than he received for the entire work of his life. The Immaculate Conception, now in the Louvre, was sold from the Soult collection for six hundred and fifteen thousand three hundred francs, or more than one hundred and twenty-three thousand dollars. At the time of its sale it was believed to be the largest price ever paid for a picture.

Sebastian Gomez (about 1620) was a mulatto slave of Murillo’s, and like Pareja he secretly learned to paint. At last one day when Murillo left a sketch of a head of the Virgin on his easel Gomez dared to finish it. Murillo was glad to find that he had made a painter of his slave, and though the pictures of Gomez were full of faults his color was much like that of his master. Two of his pictures are in the Museum of Seville. He did not live long after Murillo’s death in 1682.

Don Alonso Miguel de Tobar (1678-1758) never attained to greatness. His best original pictures were portraits. He made a great number of copies of the works of Murillo, and was chiefly famous for these pictures. There is little doubt that many pictures attributed to Murillo are replicas, or copies by the hand of Tobar.

The school of Valencia flourished from 1506 to 1680. Vicente de Joanes (about 1506-1579) was a painter of religious pictures who is scarcely known out of Spain, and in that country his pictures are, almost without exception, in churches and convents. He was very devout, and began his works with fasting and prayer. It is related that on one occasion a Jesuit of Valencia had a vision in which the Virgin Mary appeared to him, and commanded him to have a picture painted of her in a dress like that she then wore, which was a white robe with a blue mantle. She was to be represented standing on a crescent with the mystic dove floating above her; her Son was to crown her, while the Father was to lean from the clouds above all.

The Jesuit selected Joanes to be the painter of this work, and though he fasted and prayed much he could not paint it so as to please himself or the Jesuit. At last his pious zeal overcame all obstacles, and his picture was hung above the altar of the Immaculate in the convent of the Jesuits. It was very beautiful—the artists praised it, the monks believed that it had a miraculous power, and it was known as “La Purisima,” or the perfectly pure one.

Joanes excelled in his pictures of Christ. He seemed to have conceived the very Christ of the Scriptures, the realization of the visions of St. John, or of the poetry of Solomon. In these pictures he combined majesty with grace and love with strength. Joanes frequently represented the Last Supper, and introduced a cup which is known as the Holy Chalice of Valencia. It is made of agate and adorned with gold and gems, and was believed to have been used by Christ at his Last Supper with his disciples. Some of the portraits painted by Joanes are very fine. In manner and general effect his works are strangely like those of the great Raphael.

Francisco de Ribalta (1550-1628) was really the head of the school of Valencia, and one of the best historical painters of Spain. He studied his art first in Valencia, and there fell in love with the daughter of his master. The father refused him his suit, and the young couple parted in deep sorrow. Ribalta went to Italy, where he made such progress, and gained such fame that when he returned to Valencia he had no trouble in marrying his old master’s daughter. Valencia has more pictures by Ribalta than are found elsewhere. Out of Spain they are very rare. One of his works is at Magdalene College, Oxford.

One peculiarity of the Spanish painters was that they painted the extremes of emotion. Their subjects represented the ecstacy of bliss or the most excruciating agony. They did not seem to have as much middle ground or to know as much of moderate emotions as the painters of other nations. Ribalta was no exception to this rule, and some of his pictures are painful to look at. His portraits are fine, and represent the most powerful men of Valencia of the time in which he lived.

Josef de Ribera was a native of Valencia, but lived and studied in Italy, and so became more of an Italian than a Spanish master. I have spoken of him in connection with the Naturalists and their school at Naples.

Alonso Cano (1601-1667) was a very important artist, and cannot be said to belong to any school. He was born at Granada, and studied under masters of Seville, both in painting and sculpture. He became the best Spanish artist who studied in Spain only. He was something of an architect also, and his various talents acquired a high place for him among artists; but his temper was such as to cause him much trouble, and it so interfered with his life that he did not attain to the position to which his artistic gifts entitled him.

In 1637 he fought a duel, and was obliged to flee from Madrid, and in 1644 his wife was found murdered in her bed. Cano was suspected of the crime, and although he fled he was found, and brought back, and put to the torture. He made no confession, and was set at liberty; but many people believed in his guilt. He still held his office as painter to the king, and was sometimes employed on important works; but he determined to remove to his native Granada and become a priest. Philip IV. appointed him canon, and after he held this office he was still employed as a painter and sculptor by private persons, as well as by religious bodies, and was even sent to Malaga to superintend improvements in the cathedral there. But his temper led him into so many broils that at length, in 1659, the chapter of Granada deprived him of his office. He went to the king with his complaints, and was again made a canon; but he was so angry that he never would use his brush or his chisel in the service of the Cathedral of Granada.

His life was now devoted to charity and good works. He gave away all his money as soon as he received it. When his purse was empty he would go into a shop, and beg a pencil and paper, and sketching a head or other design would mark the price on it, and give it to a beggar with directions for finding a purchaser for it. After his death large numbers of these charity works were collected.

One of his strong characteristics was hatred of the Jews. He would cross the street, in order not to meet one of them, and would throw away a garment that had brushed against one of the race. One day he went home, and found his housekeeper bargaining with a Jew; he chased him away with great fury, sent the woman off to be purified, repaved the spot where the Jew had stood, and gave the shoes in which he had chased him to a servant. When about to die Cano would not receive the sacrament from the priest who was present, because he had communicated with Jews, and when a rude crucifix was held before him he pushed it away. When he was reproved for this he said: “Vex me not with this thing; but give me a simple cross that I may adore it, both as it is, and as I can figure it in my mind.” When this was done, it is said that he died in a most edifying manner.

Very few of Cano’s architectural works remain; a few drawings of this sort are in the Louvre which are simple and elegant in style. The finest carving by him is a small figure of the Virgin, now in the Cathedral of Granada. Eight of his pictures are in the Queen of Spain’s gallery at Madrid, and the Church of Getafe, the Cathedral of Granada and that of Malaga have his works. A beautiful madonna, which was one of his latest works, is in the chapel of the Cathedral of Valencia, and is lighted by votive tapers only. His pictures are rare out of Spain. One of his portraits is in the Louvre. Other works are in Berlin, Dresden, Munich, and the Hermitage, St. Petersburg.

The last Spanish painter of whom I shall speak belongs to a much later period. Francisco Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828) was a student in Rome, and after his return to Spain lived in fine style in a villa near Madrid. He was painter to Charles IV., and was always employed on orders from the nobility. He painted portraits and religious pictures, but his chief excellence was in painting caricatures. He was never weary of painting the priests and monks in all sorts of ridiculous ways. He made them in the form of apes and asses, and may be called the Hogarth of Spain, so well did he hold up the people about him to ridicule. He painted with great boldness and could use a sponge or stick in place of a brush. Sometimes he made a picture with his palette-knife, and put in the fine touches with his thumb. He executed engravings also, and published eighty prints which he called “Caprices.” These were very famous; they were satires upon all Spanish laws and customs. He also made a series of plates about the French invasion, thirty-three prints of scenes in the bull-ring, and etchings of some of the works of Velasquez. Portraits of Charles IV. and his queen by Goya are in the museum at Madrid. Works of his are in the Louvre and in the National Gallery in London. His pictures sell for large prices. In 1870 his picture of Charlotte Corday sold for five hundred and eighty-four pounds.