Books Recommended: As before Fromentin, (Waagen's) Kügler; Amand-Durand, Œuvre de Rembrandt; Archief voor Nederlandsche Kunst-geschiedenis; Blanc, Œuvre de Rembrandt; Bode, Franz Hals und seine Schule; Bode, Studien zur Geschichte der Hollandischen Malerei; Bode, Adriaan van Ostade; Brown, Rembrandt; Burger (Th. Thoré), Les Musées de la Hollande; Havard, La Peinture Hollandaise; Michel, Rembrandt; Michel, Gerard Terburg et sa Famille; Mantz, Adrien Brouwer; Rooses, Dutch Painters of the Nineteenth Century; Rooses, Rubens; Schmidt, Das Leben des Malers Adriaen Brouwer; Van der Willigen, Les Artistes de Harlem; Van Mander, Leven der Nederlandsche en Hoogduitsche Schilders; Vosmaer, Rembrandt, sa Vie et ses Œuvres; Westrheene,Jan Steen, Étude sur l'Art en Hollande; Van Dyke, Old Dutch and Flemish Masters.

THE DUTCH PEOPLE AND THEIR ART: Though Holland produced a somewhat different quality of art from Flanders and Belgium, yet in many respects the people at the north were not very different from those at the south of the Netherlands. They were perhaps less versatile, less volatile, less like the French and more like the Germans. Fond of homely joys and the quiet peace of town and domestic life, the Dutch were matter-of-fact in all things, sturdy, honest, coarse at times, sufficient unto themselves, and caring little for what other people did. Just so with their painters. They were realistic at times to grotesqueness. Little troubled with fine poetic frenzies they painted their own lives in street, town-hall, tavern, and kitchen, conscious that it was good because true to themselves.

At first Dutch art was influenced, even confounded, with that of Flanders. The Van Eycks led the way, and painters like Bouts and others, though Dutch by birth, became Flemish by adoption in their art at least. When the Flemish painters fell to copying Italy some of the Dutch followed them, but with no great enthusiasm. Suddenly, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, when Holland had gained political independence, Dutch art struck off by itself, became original, became famous. It pictured native life with verve, skill, keenness of insight, and fine pictorial view. Limited it was; it never soared like Italian art, never became universal or world-embracing. It was distinct, individual, national, something that spoke for Holland, but little beyond it.

In subject there were few historical canvases such as the Italians and French produced. The nearest approach to them were the paintings of shooting companies, or groups of burghers and syndics, and these were merely elaborations and enlargements of the portrait which the Dutch loved best of all. As a whole their subjects were single figures or small groups in interiors, quiet scenes, family conferences, smokers, card-players, drinkers, landscapes, still-life, architectural pieces. When they undertook the large canvas with many figures, they were often unsatisfactory. Even Rembrandt was so. The chief medium was oil, used upon panel or canvas. Fresco was probably used in the early days, but the climate was too damp for it and it was abandoned. It was perhaps the dampness of the northern climate that led to the adaptation of the oil medium, something the Van Eycks are credited with inaugurating.

FIG. 81.—HALS. PORTRAIT OF A LADY.

FIG. 81.—HALS. PORTRAIT OF A LADY.THE EARLY PAINTING: The early work has, for the great part, perished through time and the fierceness with which the Iconoclastic warfare was waged. That which remains to-day is closely allied in method and style to Flemish painting under the Van Eycks. Ouwater is one of the earliest names that appears, and perhaps for that reason he has been called the founder of the school. He was remarked in his time for the excellent painting of background landscapes; but there is little authentic by him left to us from which we may form an opinion.[17] Geertjen van St. Jan (about 1475) was evidently a pupil of his, and from him there are two wings of an altar in the Vienna Gallery, supposed to be genuine. Bouts and Mostert have been spoken of under the Flemish school. Bosch (1460?-1516) was a man of some individuality who produced fantastic purgatories that were popular in their time and are known to-day through engravings. Engelbrechsten (1468-1533) was Dutch by birth and in his art, and yet probably got his inspiration from the Van Eyck school. The works attributed to him are doubtful, though two in the Leyden Gallery seem to be authentic. He was the master of Lucas van Leyden (1494-1533), the leading artist of the early period. Lucas van Leyden was a personal friend of Albrecht Dürer, the German painter, and in his art he was not unlike him. A man with a singularly lean type, a little awkward in composition, brilliant in color, and warm in tone, he was, despite his archaic-looking work, an artist of much ability and originality. At first he was inclined toward Flemish methods, with an exaggerated realism in facial expression. In his middle period he was distinctly Dutch, but in his later days he came under Italian influence, and with a weakening effect upon his art. Taking his work as a whole, it was the strongest of all the early Dutch painters.

[17] A Raising of Lazarus is in the Berlin Gallery.

SIXTEENTH CENTURY: This century was a period of Italian imitation, probably superinduced by the action of the Flemings at Antwerp. The movement was somewhat like the Flemish one, but not so extensive or so productive. There was hardly a painter of rank in Holland during the whole century. Scorel (1495-1562) was the leader, and he probably got his first liking for Italian art through Mabuse at Antwerp. He afterward went to Italy, studied Raphael and Michael Angelo, and returned to Utrecht to open a school and introduce Italian art into Holland. A large number of pupils followed him, but their work was lacking in true originality. Heemskerck (1498-1574) and Cornelis van Haarlem (1562-1638), with Steenwyck (1550?-1604), were some of the more important men of the century, but none of them was above a common average.

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY: Beginning with the first quarter of this century came the great art of the Dutch people, founded on themselves and rooted in their native character. Italian methods were abandoned, and the Dutch told the story of their own lives in their own manner, with truth, vigor, and skill. There were so many painters in Holland during this period that it will be necessary to divide them into groups and mention only the prominent names.

PORTRAIT AND FIGURE PAINTERS: The real inaugurators of Dutch portraiture were Mierevelt, Hals, Ravesteyn, and De Keyser. Mierevelt (1567-1641) was one of the earliest, a prolific painter, fond of the aristocratic sitter, and indulging in a great deal of elegance in his accessories of dress and the like. He had a slight, smooth brush, much detail, and a profusion of color. Quite the reverse of him wasFranz Hals (1584?-1666), one of the most remarkable painters of portraits with which history acquaints us. In giving the sense of life and personal physical presence, he was unexcelled by any one. What he saw he could portray with the most telling reality. In drawing and modelling he was usually good; in coloring he was excellent, though in his late work sombre; in brush-handling he was one of the great masters. Strong, virile, yet easy and facile, he seemed to produce without effort. His brush was very broad in its sweep, very sure, very true. Occasionally in his late painting facility ran to the ineffectual, but usually he was certainty itself. His best work was in portraiture, and the most important of this is to be seen at Haarlem, where he died after a rather careless life. As a painter, pure and simple, he is almost to be ranked beside Velasquez; as a poet, a thinker, a man of lofty imagination, his work gives us little enlightenment except in so far as it shows a fine feeling for masses of color and problems of light. Though excellent portrait-painters, Ravesteyn (1572?-1657) and De Keyser (1596?-1679) do not provoke enthusiasm. They were quiet, conservative, dignified, painting civic guards and societies with a knowing brush and lively color, giving the truth of physiognomy, but not with that verve of the artist so conspicuous in Hals, nor with that unity of the group so essential in the making of a picture.

FIG. 82.—REMBRANDT. HEAD OF WOMAN. NAT. GAL. LONDON.

FIG. 82.—REMBRANDT. HEAD OF WOMAN. NAT. GAL. LONDON.The next man in chronological order is Rembrandt (1607?-1669), the greatest painter in Dutch art. He was a pupil of Swanenburch and Lastman, but his great knowledge of nature and his craft came largely from the direct study of the model. Settled at Amsterdam, he quickly rose to fame, had a large following of pupils, and his influence was felt through all Dutch painting. The portrait was emphatically his strongest work. The many-figured group he was not always successful in composing or lighting. His method of work rather fitted him for the portrait and unfitted him for the large historical piece. He built up the importance of certain features by dragging down all other features. This was largely shown in his handling of illumination. Strong in a few high lights on cheek, chin, or white linen, the rest of the picture was submerged in shadow, under which color was unmercifully sacrificed. This was not the best method for a large, many-figured piece, but was singularly well suited to the portrait. It produced strength by contrast. "Forced" it was undoubtedly, and not always true to nature, yet nevertheless most potent in Rembrandt's hands. He was an arbitrary though perfect master of light-and-shade, and unusually effective in luminous and transparent shadows. In color he was again arbitrary but forcible and harmonious. In brush-work he was at times labored, but almost always effective.

Mentally he was a man keen to observe, assimilate, and express his impressions in a few simple truths. His conception was localized with his own people and time (he never built up the imaginary or followed Italy), and yet into types taken from the streets and shops of Amsterdam he infused the very largest humanity through his inherent sympathy with man. Dramatic, even tragic, he was; yet this was not so apparent in vehement action as in passionate expression. He had a powerful way of striking universal truths through the human face, the turned head, bent body, or outstretched hand. His people have character, dignity, and a pervading feeling that they are the great types of the Dutch race—people of substantial physique, slow in thought and impulse, yet capable of feeling, comprehending, enjoying, suffering.

His landscapes, again, were a synthesis of all landscapes, a grouping of the great truths of light, air, shadow, space. Whatever he turned his hand to was treated with that breadth of view that overlooked the little and grasped the great. He painted many subjects. His earliest work dates from 1627, and is a little hard and sharp in detail and cold in coloring. After 1654 he grew broader in handling and warmer in tone, running to golden browns, and, toward the end of his career, to rather hot tones. His life was embittered by many misfortunes, but these never seem to have affected his art except to deepen it. He painted on to the last, convinced that his own view was the true one, and producing works that rank second to none in the history of painting.

Rembrandt's influence upon Dutch art was far-reaching, and appeared immediately in the works of his many pupils. They all followed his methods of handling light-and-shade, but no one of them ever equalled him, though they produced work of much merit. Bol (1611-1680) was chiefly a portrait-painter, with a pervading yellow tone and some pallor of flesh-coloring—a man of ability who mistakenly followed Rubens in the latter part of his life. Flinck (1615-1660) at one time followed Rembrandt so closely that his work has passed for that of the master; but latterly he, too, came under Flemish influence. Next to Eeckhout he was probably the nearest to Rembrandt in methods of all the pupils. Eeckhout (1621-1674) was really a Rembrandt imitator, but his hand was weak and his color hot. Maes (1632-1693) was the most successful manager of light after the school formula, and succeeded very well with warmth and richness of color, especially with his reds. The other Rembrandt pupils and followers were Poorter (fl. 1635-1643), Victoors (1620?-1672?), Koninck (1619-1688), Fabritius (1624-1654), and Backer (1608?-1651).

Van der Helst (1612?-1670) stands apart from this school, and seems to have followed more the portrait style of De Keyser. He was a realistic, precise painter, with much excellence of modelling in head and hands, and with fine carriage and dignity in the figure. In composition he hardly held his characters in group owing to a sacrifice of values, and in color he was often "spotty," and lacking in the unity of mass.

THE GENRE PAINTERS: This heading embraces those who may be called the "Little Dutchmen," because of the small scale of their pictures and their genre subjects. Gerard Dou (1613-1675) is indicative of the class without fully representing it. He was a pupil of Rembrandt, but his work gave little report of this. It was smaller, more delicate in detail, more petty in conception. He was a man great in little things, one who wasted strength on the minutiæ of dress, or table-cloth, or the texture of furniture without grasping the mass or color significance of the whole scene. There was infinite detail about his work, and that gave it popularity; but as art it held, and holds to-day, little higher place than the work of Metsu (1630-1667), Van Mieris (1635-1681), Netscher (1639-1684), or Schalcken (1643-1706), all of whom produced the interior piece with figures elaborate in accidental effects. Van Ostade (1610-1685), though dealing with the small canvas, and portraying peasant life with perhaps unnecessary coarseness, was a much stronger painter than the men just mentioned. He was the favorite pupil of Hals and the master of Jan Steen. With little delicacy in choice of subject he had much delicacy in color, taste in arrangement, and skill in handling. His brush was precise but not finical.

FIG. 83.—J. VAN RUISDAEL. LANDSCAPE.

FIG. 83.—J. VAN RUISDAEL. LANDSCAPE.By far the best painter among all the "Little Dutchmen" was Terburg (1617?-1681), a painter of interiors, small portraits, conversation pictures, and the like. Though of diminutive scale his work has the largeness of view characteristic of genius, and the skilled technic of a thorough craftsman. Terburg was a travelled man, visiting Italy, where he studied Titian, returning to Holland to study Rembrandt, finally at Madrid studying Velasquez. He was a painter of much culture, and the keynote of his art is refinement. Quiet and dignified he carried taste through all branches of his art. In subject he was rather elevated, in color subdued with broken tones, in composition simple, in brush-work sure, vivacious, and yet unobtrusive. Selection in his characters was followed by reserve in using them. Detail was not very apparent. A few people with some accessory objects were all that he required to make a picture. Perhaps his best qualities appear in a number of small portraits remarkable for their distinction and aristocratic grace.

Steen (1626?-1679) was almost the opposite of Terburg, a man of sarcastic flings and coarse humor who satirized his own time with little reserve. He developed under Hals and Van Ostade, favoring the latter in his interiors, family scenes, and drunken debauches. He was a master of physiognomy, and depicted it with rare if rather unpleasant truth. If he had little refinement in his themes he certainly handled them as a painter with delicacy. At his best his many figured groups were exceedingly well composed, his color was of good quality (with a fondness for yellows), and his brush was as limpid and graceful as though painting angels instead of Dutch boors. He was really one of the fine brushmen of Holland, a man greatly admired by Sir Joshua Reynolds, and many an artist since; but not a man of high intellectual pitch as compared with Terburg, for instance.

Pieter de Hooghe (1632?-1681) was a painter of purely pictorial effects, beginning and ending a picture in a scheme of color, atmosphere, clever composition, and above all the play of light-and-shade. He was one of the early masters of full sunlight, painting it falling across a court-yard or streaming through a window with marvellous truth and poetry. His subjects were commonplace enough. An interior with a figure or two in the middle distance, and a passage-way leading into a lighted background were sufficient for him. These formed a skeleton which he clothed in a half-tone shadow, pierced with warm yellow light, enriched with rare colors, usually garnet reds and deep yellows repeated in the different planes, and surrounded with a subtle pervading atmosphere. As a brushman he was easy but not distinguished, and often his drawing was not correct; but in the placing of color masses and in composing by color and light he was a master of the first rank. Little is known about his life. He probably formed himself on Fabritius or Rembrandt at second-hand, but little trace of the latter is apparent in his work. He seems not to have achieved much fame until late years, and then rather in England than in his own country.

Jan van der Meer of Delft (1632-1675), one of the most charming of all the genre painters, was allied to De Hooghe in his pictorial point of view and interior subjects. Unfortunately there is little left to us of this master, but the few extant examples serve to show him a painter of rare qualities in light, in color, and in atmosphere. He was a remarkable man for his handling of blues, reds, and yellows; and in the tonic relations of a picture he was a master second to no one. Fabritius is supposed to have influenced him.

THE LANDSCAPE PAINTERS: The painters of the Netherlands were probably the first, beginning with Bril, to paint landscape for its own sake, and as a picture motive in itself. Before them it had been used as a background for the figure, and was so used by many of the Dutchmen themselves. It has been said that these landscape-painters were also the first ones to paint landscape realistically, but that is true only in part. They studied natural forms, as did, indeed, Bellini in the Venetian school; they learned something of perspective, air, tree anatomy, and the appearance of water; but no Dutch painter of landscape in the seventeenth century grasped the full color of Holland or painted its many varied lights. They indulged in a meagre conventional palette of grays, greens, and browns, whereas Holland is full of brilliant hues.

FIG. 84.—HOBBEMA. THE WATER-WHEEL. AMSTERDAM MUS.

FIG. 84.—HOBBEMA. THE WATER-WHEEL. AMSTERDAM MUS.Van Goyen (1596-1656) was one of the earliest of the seventeenth-century landscapists. In subject he was fond of the Dutch bays, harbors, rivers, and canals with shipping, windmills, and houses. His sky line was generally given low, his water silvery, and his sky misty and luminous with bursts of white light. In color he was subdued, and in perspective quite cunning at times. Salomon van Ruisdael (1600?-1670) was his follower, if not his pupil. He had the same sobriety of color as his master, and was a mannered and prosaic painter in details, such as leaves and tree-branches. In composition he was good, but his art had only a slight basis upon reality, though it looks to be realistic at first sight. He had a formula for doing landscape which he varied only in a slight way, and this conventionality ran through all his work.Molyn (1600?-1661) was a painter who showed limited truth to nature in flat and hilly landscapes, transparent skies, and warm coloring. His extant works are few in number. Wynants (1615?-1679?) was more of a realist in natural appearance than any of the others, a man who evidently studied directly from nature in details of vegetation, plants, trees, roads, grasses, and the like. Most of the figures and animals in his landscapes were painted by other hands. He himself was a pure landscape-painter, excelling in light and aërial perspective, but not remarkable in color. Van der Neer (1603-1677) and Everdingen(1621?-1675) were two other contemporary painters of merit.

The best landscapist following the first men of the century was Jacob van Ruisdael (1625?-1682), the nephew of Salomon van Ruisdael. He is put down, with perhaps unnecessary emphasis, as the greatest landscape-painter of the Dutch school. He was undoubtedly the equal of any of his time, though not so near to nature, perhaps, as Hobbema. He was a man of imagination, who at first pictured the Dutch country about Haarlem, and afterward took up with the romantic landscape of Van Everdingen. This landscape bears a resemblance to the Norwegian country, abounding, as it does, in mountains, heavy dark woods, and rushing torrents. There is considerable poetry in its composition, its gloomy skies, and darkened lights. It is mournful, suggestive, wild, usually unpeopled. There was much of the methodical in its putting together, and in color it was cold, and limited to a few tones. Many of Ruisdael's works have darkened through time. Little is known about the painter's life except that he was not appreciated in his own time and died in the almshouse.

Hobbema (1638?-1709) was probably the pupil of Jacob van Ruisdael, and ranks with him, if not above him, in seventeenth-century landscape painting. Ruisdael hardly ever painted sunlight, whereas Hobbema rather affected it in quiet wood-scenes or roadways with little pools of water and a mill. He was a freer man with the brush than Ruisdael, and knew more about the natural appearance of trees, skies, and lights; but, like his master, his view of nature found no favor in his own land. Most of his work is in England, where it had not a little to do with influencing such painters as Constable and others at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

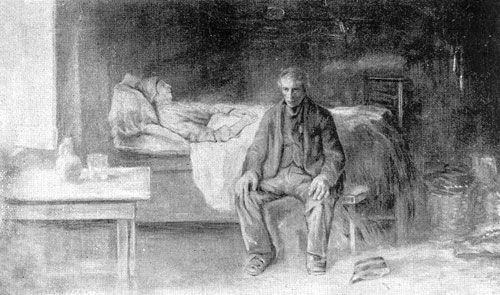

FIG. 85.—ISRAELS. ALONE IN THE WORLD.

FIG. 85.—ISRAELS. ALONE IN THE WORLD.LANDSCAPE WITH CATTLE: Here we meet with Wouverman (1619-1668), a painter of horses, cavalry, battles, and riding parties placed in landscape. His landscape is bright and his horses are spirited in action. There is some mannerism apparent in his reiterated concentration of light on a white horse, and some repetition in his canvases, of which there are many; but on the whole he was an interesting, if smooth and neat painter. Paul Potter (1625-1654) hardly merited his great repute. He was a harsh, exact recorder of facts, often tin-like or woodeny in his cattle, and not in any way remarkable in his landscapes, least of all in their composition. The Young Bull at the Hague is an ambitious piece of drawing, but is not successful in color, light, or ensemble. It is a brittle work all through, and not nearly so good as some smaller things in the National Gallery London, and in the Louvre. Adrien van de Velde (1635?-1672) was short-lived, like Potter, but managed to do a prodigious amount of work, showing cattle and figures in landscape with much technical ability and good feeling. He was particularly good in composition and the subtle gradation of neutral tints. A little of the Italian influence appeared in his work, and with the men who came with him and after him the Italian imitation became very pronounced. Aelbert Cuyp (1620-1691) was a many-sided painter, adopting at various times different styles, but was enough of a genius to be himself always. He is best known to us, perhaps, by his yellow sunlight effects along rivers, with cattle in the foreground, though he painted still-life, and even portraits and marines. In composing a group he was knowing, recording natural effects with power; in light and atmosphere he was one of the best of his time, and in texture and color refined, and frequently brilliant. Both (1610-1650?), Berchem (1620-1683), Du Jardin (1622?-1678), followed the Italian tradition of Claude Lorrain, producing semi-classic landscapes, never very convincing in their originality. Van der Heyden(1637-1712), should be mentioned as an excellent, if minute, painter of architecture with remarkable atmospheric effects.

MARINE AND STILL-LIFE PAINTERS: There were two pre-eminent marine painters in this seventeenth century, Willem van de Velde (1633-1707) and Backhuisen (1631-1708). The sea was not an unusual subject with the Dutch landscapists. Van Goyen, Simon de Vlieger (1601?-1660?), Cuyp, Willem van de Velde the Elder (1611?-1693), all employed it; but it was Van de Velde the Younger who really stood at the head of the marine painters. He knew his subject thoroughly, having been well grounded in it by his father and De Vlieger, so that the painting of the Dutch fleets and harbors was a part of his nature. He preferred the quiet haven to the open sea. Smooth water, calm skies, silvery light, and boats lying listlessly at anchor with drooping sails, made up his usual subject. The color was almost always in a key of silver and gray, very charming in its harmony and serenity, but a little thin. Both he and his father went to England and entered the service of the English king, and thereafter did English fleets rather than Dutch ones. Backhuisen was quite the reverse of Van de Velde in preferring the tempest to the calm of the sea. He also used more brilliant and varied colors, but he was not so happy in harmony as Van de Velde. There was often dryness in his handling, and something too much of the theatrical in his wrecks on rocky shores.

The still-life painters of Holland were all of them rather petty in their emphasis of details such as figures on table-covers, water-drops on flowers, and fur on rabbits. It was labored work with little of the art spirit about it, except as the composition showed good masses. A number of these painters gained celebrity in their day by their microscopic labor over fruits, flowers, and the like, but they have no great rank at the present time. Jan van Heem (1600?1684?) was perhaps the best painter of flowers among them. Van Huysum (1682-1749) succeeded with the same subject beyond his deserts. Hondecoeter(1636-1695) was a unique painter of poultry; Weenix (1640-1719) and Van Aelst (1620-1679), of dead game; Kalf (1630?-1693), of pots, pans, dishes, and vegetables.

EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: This was a period of decadence during which there was no originality worth speaking about among the Dutch painters. Realism in minute features was carried to the extreme, and imitation of the early men took the place of invention. Everything was prettified and elaborated until there was a porcelain smoothness and a photographic exactness inconsistent with true art. Adriaan van der Werff (1659-1722), and Philip van Dyck (1683-1753) with their "ideal" inanities are typical of the century's art. There was nothing to commend it. The lowest point of affectation had been reached.

NINETEENTH CENTURY: The Dutch painters, unlike the Belgians, have almost always been true to their own traditions and their own country. Even in decadence the most of them feebly followed their own painters rather than those of Italy and France, and in the early nineteenth century they were not affected by the French classicism of David. Later on there came into vogue an art that had some affinity with that of Millet and Courbet in France. It was the Dutch version of modern sentiment about the laboring classes, founded on the modern life of Holland, yet in reality a continuation of the style or genre practised by the early Dutchmen. Israels (1824-) is a revival or a survival of Rembrandtesque methods with a sentiment and feeling akin to the French Millet. He deals almost exclusively with peasant life, showing fisher-folk and the like in their cottage interiors, at the table, or before the fire, with good effects of light, atmosphere, and much pathos. Technically he is rather labored and heavy in handling, but usually effective with sombre color in giving the unity of a scene. Artz (1837-1890) considered himself in measure a follower of Israels, though he never studied under him. His pictures in subject are like those of Israels, but without the depth of the latter. Blommers (1845-) is another peasant painter who follows Israels at a distance, and Neuhuys (1844-) shows a similar style of work. Bosboom (1817-1891) excelled in representing interiors, showing, with much pictorial effect, the light, color, shadow, and feeling of space and air in large cathedrals.

FIG. 86.—MAUVE. SHEEP.

FIG. 86.—MAUVE. SHEEP.The brothers Maris have made a distinct impression on modern Dutch art, and, strange enough, each in a different way from the others. James Maris (1837-) studied at Paris, and is remarkable for fine, vigorous views of canals, towns, and landscapes. He is broad in handling, rather bleak in coloring, and excels in fine luminous skies and voyaging clouds. Matthew Maris (1835-), Parisian trained like his brother, lives in London, where little is seen of his work. He paints for himself and his friends, and is rather melancholy and mystical in his art. He is a recorder of visions and dreams rather than the substantial things of the earth, but always with richness of color and a fine decorative feeling. Willem Maris (1839-), sometimes called the "Silvery Maris," is a portrayer of cattle and landscape in warm sunlight and haze with a charm of color and tone often suggestive of Corot. Jongkind (1819-1891) stands by himself, Mesdag (1831-) is a fine painter of marines and sea-shores, and Mauve (1838-1888), a cattle and sheep painter, with nice sentiment and tonality, whose renown is just now somewhat disproportionate to his artistic ability. In addition there are Kever, Poggenbeek, Bastert, Baur, Breitner, Witsen,Haverman, Weissenbruch.

EXTANT WORKS: Generally speaking the best examples of the Dutch schools are still to be seen in the local museums of Holland, especially the Amsterdam and Hague Mus.; Bosch, Madrid, Antwerp, Brussels Mus.; Lucas van Leyden, Antwerp, Leyden, Munich Mus.; Scorel, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Haarlem Mus.; Heemskerck, Haarlem, Hague, Berlin, Cassel, Dresden; Steenwyck, Amsterdam, Hague, Brussels; Cornelis van Haarlem, Amsterdam, Haarlem, Brunswick.

Portrait and Figure Painters—Mierevelt, Hague, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Brunswick, Dresden, Copenhagen; Hals, best works to be seen at Haarlem, others at Amsterdam, Brussels, Hague, Berlin, Cassel, Louvre, Nat. Gal. Lon., Met. Mus. New York, Art Institute Chicago; Rembrandt, Amsterdam, Hermitage, Louvre, Munich, Berlin, Dresden, Madrid, London; Bol, Amsterdam, Hague, Dresden, Louvre;Flinck, Amsterdam, Hague, Berlin; Eeckhout, Amsterdam, Brunswick, Berlin, Munich; Maes, Nat. Gal. Lon., Rotterdam, Amsterdam, Hague, Brussels; Poorter, Amsterdam, Brussels, Dresden; Victoors, Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Brunswick, Dresden; Fabritius, Rotterdam, Amsterdam, Berlin; Van der Helst, best works at Amsterdam Mus.

Genre Painters—Examples of Dou, Metsu, Van Mieris, Netscher, Schalcken, Van Ostade, are to be seen in almost all the galleries of Europe, especially the Dutch, Belgian, German, and French galleries; Terburg, Amsterdam, Louvre, Dresden, Berlin (fine portraits); Steen, Amsterdam, Louvre, Rotterdam, Hague, Berlin, Cassel, Dresden, Vienna; De Hooghe, Nat. Gal. Lon., Louvre, Amsterdam, Hermitage; Van der Meer of Delft, Louvre, Hague, Amsterdam, Berlin, Dresden, Met. Mus. New York.

Landscape Painters—Van Goyen, Amsterdam, Fitz-William Mus. Cambridge, Louvre, Brussels, Cassel, Dresden, Berlin; Salomon van Ruisdael, Amsterdam, Brussels, Berlin, Dresden, Munich; Van der Neer, Nat. Gal. Lon., Louvre, Brussels, Amsterdam, Berlin, Dresden; Everdingen, Amsterdam, Berlin, Louvre, Brunswick, Dresden, Munich, Frankfort; Jacob van Ruisdael, Nat. Gal. Lon., Louvre, Amsterdam, Berlin, Dresden; Hobbema, best works in England, Nat. Gal. Lon., Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Dresden; Wouvermans, many works, best at Amsterdam, Cassel, Louvre; Potter, Amsterdam, Hague, Louvre, Nat. Gal. Lon.; Van de Velde, Amsterdam, Hague, Cassel, Dresden, Frankfort, Munich, Louvre; Cuyp, Amsterdam, Nat. Gal. Lon., Louvre, Munich, Dresden; examples of Both,Berchem, Du Jardin, and Van der Heyden, in almost all of the Dutch and German galleries, besides the Louvre and Nat. Gal. Lon.

Marine Painters—Willem van de Velde Elder and Younger, Backhuisen, Vlieger, together with the flower and fruit painters like Huysum, Hondecoeter, Weenix, have all been prolific workers, and almost every European gallery, especially those at London, Amsterdam, and in Germany, have examples of their works; Van der Werff and Philip van Dyck are seen at their best at Dresden.

The best works of the modern men are in private collections, many in the United States, some examples of them in the Amsterdam and Hague Museums. Also some examples of the old Dutch masters in New York Hist. Society Library, Yale School of Fine Arts, Met. Mus. New York, Boston Mus., and Chicago Institute.