In July of 1904 the eighty-seven mortal years of George Frederick Watts came to an end. He had outlived all the contemporaries and acquaintances of his youth; few, even among the now living, knew him in his middle age; while to those of the present generation, who knew little of the man though much of his work, he appeared as members of the Ionides family, thus inaugurating the series of private and public portraits for which he became so famous. The Watts of our day, however, the teacher first and the painter afterwards, had not yet come on the scene. His first aspiration towards monumental painting began in the year 1843, when in a competition for the decoration of the Houses of Parliament he gained a prize of £300 for his cartoon of "Caractacus led Captive through the Streets of Rome." At this time, when history was claiming pictorial art as her servant and expositor, young Watts carried off the prize against the whole of his competitors. This company included the well-known historical painter Haydon, who, from a sense of the impossibility of battling against his financial difficulties, and from the neglect, real or fancied, of the leading politicians, destroyed himself by his own hand.

The £300 took the successful competitor to Italy, where for four years he remained as a guest of Lord Holland. Glimpses of the Italy he gazed upon and loved are preserved for us in a landscape of the hillside town of Fiesole with blue sky and clouds, another of a castellated villa and mountains near Florence, and a third of the "Carrara Mountains near Pisa"; while of his portraiture of that day, "Lady Holland" and "Lady Dorothy Nevill" are relics of the Italian visit.

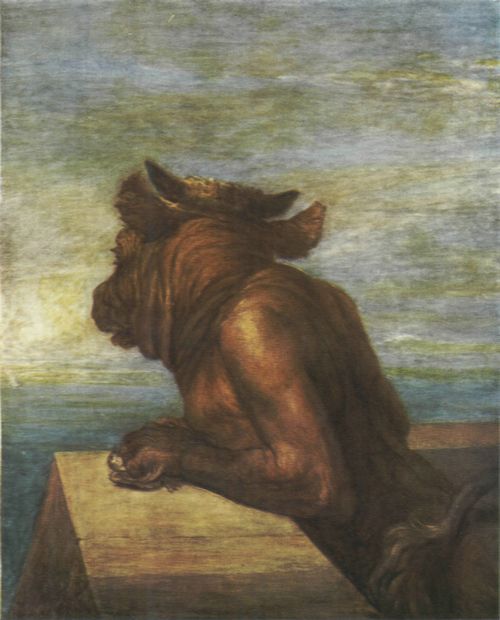

PLATE II.—THE MINOTAUR

In this terrible figure, half man, half bull, gazing over the sea from the battlement of a hill tower, we see the artist's representation of the greed and lust associated with modern civilisations. The picture was exhibited at the Winter Exhibition of the New Gallery, 1896, and formed part of the Watts Gift in 1897. It hangs in the Watts Room at the Tate Gallery.

Italy, and particularly Florence, was perpetual fascination and inspiration to Watts. There he imbibed the influences of Orcagna and Titian—influences, indeed, which were clearly represented in the next monumental painting which he attempted. It came about that Lord Holland persuaded his guest to enter a fresh competition for the decoration of the Parliament Houses, and Watts carried off the prize with his "Alfred inciting the Saxons to resist the landing of the Danes." The colour and movement of the great Italian masters, conspicuously absent from the "Caractacus" cartoon, were to be seen in this new effort, where, as has been said, the English king stands like a Raphaelesque archangel in the midst of the design.

In 1848 Watts had attained, one might almost say, the position of official historical painter to the State, a post coveted by the unfortunate Haydon; and he received a commission to paint a fresco of "St. George overcomes the Dragon," which was not completed till 1853. In this year he contributed as an appendix to the Diary of Haydon—in itself an exciting document, showing how wretched the life of an official painter then might be—a note telling of the state of historical and monumental painting in the 'forties, and of his own attitude towards it; a few of his own words, written before the days of the "poster," may be usefully quoted here:

ON THE PUBLIC EMPLOYMENT OF ARTISTS

Patriots and statesmen alike forget that the time will come when the want of great art in England will produce a gap sadly defacing the beauty of the whole national structure....

Working, for example, as an historian to record England's battles, Haydon would, no doubt, have produced a series of mighty and instructive pictures....

Why should not the Government of a mighty country undertake the decoration of all the public buildings, such as Town Halls, National Schools, and even Railway Stations....

... Or considering the walls as slates whereon the school-boy writes his figures, the great productions of other times might be reproduced, if but to be rubbed out when fine originals could be procured; for the expense would very little exceed that of whitewashing....

If, for example, on some convenient wall the whole line of British sovereigns were painted—were monumental effigies well and correctly drawn, with date, length of reign, remarkable events written underneath, these worthy objects would be attained—intellectual exercise, decoration of space, and instruction to the public.

The year 1848 was a critical time for Watts; his first allegorical picture, "Time and Oblivion," was painted, and, in the year following, "Life's Illusions" appeared on the walls of the famous Academy which contained the first works of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Watts was not of the party, though he might have been had he desired; he preferred independence.

Watts' personal life was at this time pervaded by the influence of Lord and Lady Holland, who, having returned from Florence to London, had him as a constant visitor to Holland House. In 1850 he went to live at The Dower House, an old building in the fields of Kensington. There, as a guest of the Prinsep family, he set up as a portrait painter. His host and family connections were some of the first to sit for him; and he soon gained fame in this class of work.

There was a temporary interruption in 1856, when a journey to the East, in company with Sir Charles Newton, for the purpose of opening the buried Temple of Mausolus at Halicarnassus, gave Watts further insight into the old Greek world; and, one cannot but think, stimulated his efforts, later so successful, in depicting for us so many incidents in classical lore. We have, in a view of a mountainous coast called "Asia Minor," and another, "The Isle of Cos," two charming pictorial records of this important expedition. The next six years of the artist's life were spent as a portrait painter; not, indeed, if one may say so, as a professional who would paint any one's portrait, but as a friend, who loved to devote himself to his friends.

In pursuance of his principles touching monumental work, Watts engaged himself over a period of five years on the greatest and the last of his civic paintings—namely, the "Justice; a Hemicycle of Lawgivers," to which I shall later refer.

Watts was a man who seems to have enjoyed in a singular degree the great privilege of friendship, which while it has its side of attachment, has also its side of detachment. Even in his youthful days he never "settled down," but was a visitor and guest rather than an attached scholar and student at the schools and studies. It is told of him that when just about to leave Florence, after a short visit, he casually presented a letter of introduction to Lord Holland, which immediately led to a four years' stay there, and this friendship lasted for many years after the ambassador's return to England. Other groups of friends, represented by the Ionides, the Prinseps, the Seniors, and the Russell Barringtons, seemed to have possessed him as their special treasure, in whose friendship he passed a great part of his life. Two great men, the titular chiefs of poetry and painting, were much impressed by him, and drew from him great admiration—Tennyson and Leighton; from the latter he learned much; in the sphere of music, of which Watts was passionately fond, there stands out Joachim the violinist.

Watts used to recall, as the happiest time in his life, his youthful days as a choral singer; and he always regretted that he had not become a musician. Besides being fond of singing he declared that he constantly heard (or felt) mystic music—symphonies, songs, and chorales. Only once did he receive a vision of a picture—idea, composition and colours—that was "Time, Death, and Judgment." Music, after all, is nearer to the soul of the intuitive man than any of the arts, and Watts felt this deeply. He also had considerable dramatic talent.

In 1864 some friends found for Watts a bride in the person of Miss Ellen Terry. The painter and the youthful actress were married in Kensington in February of that year, and Watts took over Little Holland House. The marriage, however, was irksome, both to the middle-aged painter and the vivacious child of sixteen, whose words, taken from her autobiography, are the best comment we possess on this incident:

"Many inaccurate stories have been told of my brief married life, and I have never contradicted them—they were so manifestly absurd. Those who can imagine the surroundings into which I, a raw girl, undeveloped in all except my training as an actress, was thrown, can imagine the situation.... I wondered at the new life and worshipped it because of its beauty. When it suddenly came to an end I was thunderstruck; and refused at first to consent to the separation which was arranged for me in much the same way as my marriage had been.... There were no vulgar accusations on either side, and the words I read in the deed of separation, 'incompatibility of temper,' more than covered the ground. Truer still would have been 'incompatibility of occupation,' and the interference of well-meaning friends.

"'The marriage was not a happy one,' they will probably say after my death, and I forestall them by saying that it was in many ways very happy indeed. What bitterness there was effaced itself in a very remarkable way." (The Story of My Life, 1908.)

In 1867, at the age of fifty, without his application or knowledge, Watts was made an Associate, and in the following year a full Member, of the Royal Academy. Younger men had preceded him in this honour, but doubtless Watts' modesty and independence secured for him a certain amount of official neglect. The old studio in Melbury Road, Kensington, was pulled down in 1868, and a new house was built suited to the painter who had chosen for himself a hermit life. The house was built in such a way as would avoid the possibility of entertaining guests, and was entirely dedicated to work. Watts continued his series of official portraits, and many of the most beautiful mythical paintings followed this change. Five years later, Watts was found at Freshwater in the Isle of Wight, and in 1876 he secured what he had so long needed, the sympathetic help and co-operation in his personal and artistic aims, in Mr. and Mrs. Russell Barrington, his neighbours.

In 1877 Watts decided, in conformity with his views on patriotic art, to give his pictures to the nation, and there followed shortly after, in 1881 and 1882, exhibitions of his works in Whitechapel and the Grosvenor Gallery. A leaflet entitled "What should a picture say?" issued with the approval of Watts, in connection with the Whitechapel Exhibition, has a characteristic answer to the question put to him.

"Roughly speaking, a picture must be regarded in the same light as written words. It must speak to the beholder and tell him something.... If a picture is a representation only, then regard it from that point of view only. If it treats of a historical event, consider whether it fairly tells its tale. Then there is another class of picture, that whose purpose is to convey suggestion and idea. You are not to look at that picture as an actual representation of facts, for it comes under the same category of dream visions, aspirations, and we have nothing very distinct except the sentiment. If the painting is bad—the writing, the language of art, it is a pity. The picture is then not so good as it should be, but the thought is there, and the thought is what the artist wanted to express, and it is or should be impressed on the spectator."

In 1886 his pictures were exhibited in New York, where they created a great sensation; but incidents connected with the exhibition, and criticisms upon it, caused the artist much nervous distress.

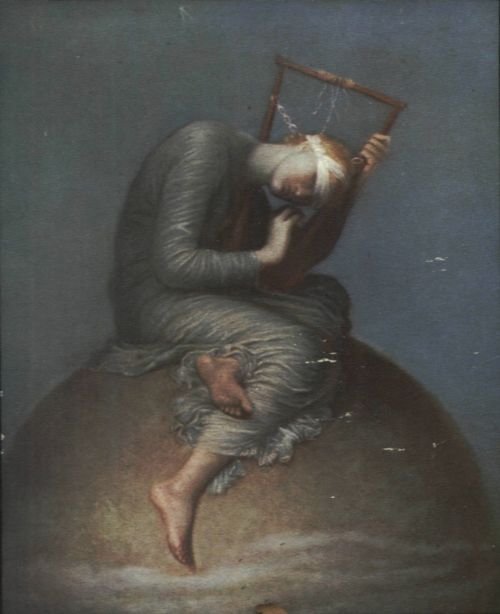

PLATE III.—HOPE

(At the Tate Gallery)

At the first glance it is rather strange that such a picture should bear such a title, but the imagery is perfectly true. The heavens are illuminated by a solitary star, and Hope bends her ear to catch the music from the last remaining string of her almost shattered lyre. The picture was painted in 1885 and given to the nation in 1897. A very fine duplicate is in the possession of Mrs. Rushton.

It was a peculiar difficulty of his nature which led him to insist, on the occasions of the London and provincial exhibitions of his pictures, that the borrowers were to make all arrangements with his frame-maker, that he should not be called upon to act in any way, and that no personal reference should be introduced. Watts always considered himself a private person; he disliked public functions and fled from them if there were any attempt to draw attention to him. His habits of work were consistent with these unusual traits. At sunrise he was at his easel. During the hot months of summer he was hard at work in his London studio, leaving for the country only for a few weeks during foggy weather.

At the age of sixty-nine Watts married Miss Mary Fraser-Tytler, with whom he journeyed to Egypt, painting there a study of the "Sphinx," one of the cleverest of his landscapes. Three years after his return, he settled at Limnerslease, Compton, in Surrey, where he took great interest in the attempt to revive industrial art among the rural population.

Twice, in 1885 and 1894, the artist refused, for private reasons, the baronetcy that other artists had accepted. He lived henceforth and died the untitled patriot and artist, George Frederick Watts.