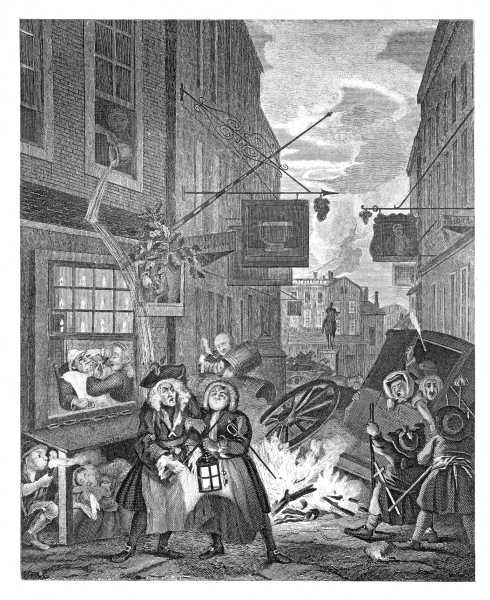

Mr. Walpole very truly observes, that this print is inferior to the three others; there is, however, broad humour in some of the figures.

The wounded free-mason, who, in zeal of brotherly love, has drank his bumpers to the craft till he is unable to find his way home, is under the guidance of a waiter. This has been generally considered as intended for Sir Thomas de Veil, and, from an authenticated portrait which I have seen, I am, says Mr. Ireland, inclined to think it is, notwithstanding Sir John Hawkins asserts, that "he could discover no resemblance." When the knight saw him in his magisterial capacity, he was probably sober and sedate; here he is represented a little disguised. The British Xantippe showering her favours from the window upon his head, may have its source in that respect which the inmates of such houses as the Rummer Tavern had for a justice of peace. On the resignation of Mr. Horace Walpole, in February, 1738, De Veil was appointed inspector-general of the imports and exports, and was so severe against the retailers of spirituous liquors, that one Allen headed a gang of rioters for the purpose of pulling down his house, and bringing to a summary punishment two informers who were there concealed. Allen was tried for this offence, and acquitted, upon the jury's verdict declaring him lunatic.

The waiter who supports his worship, seems, from the patch upon his forehead, to have been in a recent affray; but what use he can have for a lantern, it is not easy to divine, unless he is conducting his charge to some place where there is neither moonlight nor illumination.

The Salisbury flying coach oversetting and broken, by passing through the bonfire, is said to be an intended burlesque upon a right honourable peer, who was accustomed to drive his own carriage over hedges, ditches, and rivers; and has been sometimes known to drive three or four of his maid servants into a deep water, and there leave them in the coach to shift for themselves.

The butcher, and little fellow, who are assisting the terrified passengers, are possibly free and accepted masons. One of them seems to have a mop in his hand;—the pail is out of sight.

To crown the joys of the populace, a man with a pipe in his mouth is filling a capacious hogshead with British Burgundy.

The joint operation of shaving and bleeding, performed by a drunken 'prentice on a greasy oilman, does not seen a very natural exhibition on a rejoicing night.

The poor wretches under the barber's bench display a prospect of penury and wretchedness, which it is to be hoped is not so common now, as it was then.

In the distance is a cart laden with furniture, which some unfortunate tenant is removing out of the reach of his landlord's execution.

There is humour in the barber's sign and inscription; "Shaving, bleeding, and teeth drawn with a touch. Ecce signum!"

By the oaken boughs on the sign, and the oak leaves in the free-masons' hats, it seems that this rejoicing night is the twenty-ninth of May, the anniversary of our second Charles's restoration; that happy day when, according to our old ballad, "The king enjoyed his own again." This might be one reason for the artist choosing a scene contiguous to the beautiful equestrian statue of Charles the First.

In the distance we see a house on fire; an accident very likely to happen on such a night as this.

On this spot once stood the cross erected by Edward the First, as a memorial of affection for his beloved queen Eleanor, whose remains were here rested on their way to the place of sepulture. It was formed from a design by Cavalini, and destroyed by the religious fury of the Reformers. In its place, in the year 1678, was erected the animated equestrian statue which now remains. It was cast in brass, in the year 1633, by Le Sœur; I think by order of that munificent encourager of the arts, Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel. The parliament ordered it to be sold, and broken to pieces; but John River, the brazier who purchased it, having more taste than his employers, seeing, with the prophetic eye of good sense, that the powers which were would not remain rulers very long, dug a hole in his garden in Holborn, and buried it unmutilated. To prove his obedience to their order, he produced to his masters several pieces of brass, which he told them were parts of the statue. M. de Archenholtz adds further, that the brazier, with the true spirit of trade, cast a great number of handles for knives and forks, and offered them for sale, as composed of the brass which had formed the statue. They were eagerly sought for, and purchased,—by the loyalists from affection to their murdered monarch,—by the other party, as trophies of triumph.

The original pictures of Morning and Noon were sold to the Duke of Ancaster for fifty-seven guineas; Evening and Night to Sir William Heathcote, for sixty-four guineas.

NIGHT.

NIGHT.