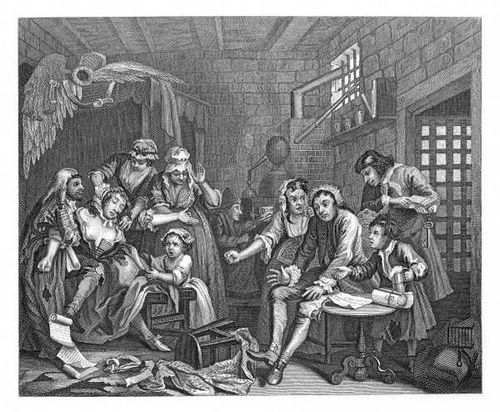

By a very natural transition Mr. Hogarth has passed his hero from a gaming house into a prison—the inevitable consequence of extravagance. He is here represented in a most distressing situation, without a coat to his back, without money, without a friend to help him. Beggared by a course of ill-luck, the common attendant on the gamester, having first made away with every valuable he was master of, and having now no other resource left to retrieve his wretched circumstances, he at last, vainly promising himself success, commences author, and attempts, though inadequate to the task, to write a play, which is lying on the table, just returned with an answer from the manager of the theatre, to whom he had offered it, that his piece would by no means do. Struck speechless with this disastrous occurrence, all his hopes vanish, and his most sanguine expectations are changed into dejection of spirit. To heighten his distress, he is approached by his wife, and bitterly upbraided for his perfidy in concealing from her his former connexions (with that unhappy girl who is here present with her child, the innocent offspring of her amours, fainting at the sight of his misfortunes, being unable to relieve him farther), and plunging her into those difficulties she never shall be able to surmount. To add to his misery, we see the under-turnkey pressing him for his prison fees, or garnish-money, and the boy refusing to leave the beer he ordered, without being first paid for it. Among those assisting the fainting mother, one of whom we observe clapping her hand, another applying the drops, is a man crusted over, as it were, with the rust of a gaol, supposed to have started from his dream, having been disturbed by the noise at a time when he was settling some affairs of state; to have left his great plan unfinished, and to have hurried to the assistance of distress. We are told, by the papers falling from his lap, one of which contains a scheme for paying the national debt, that his confinement is owing to that itch of politics some persons are troubled with, who will neglect their own affairs, in order to busy themselves in that which noways concerns them, and which they in no respect understand, though their immediate ruin shall follow it: nay, so infatuated do we find him, so taken up with his beloved object, as not to bestow a few minutes on the decency of his person. In the back of the room is one who owes his ruin to an indefatigable search after the philosopher's stone. Strange and unaccountable!—Hence we are taught by these characters, as well as by the pair of human wings on the tester of the bed, that scheming is the sure and certain road to beggary: and that more owe their misfortunes to wild and romantic notions, than to any accident they meet with in life.

In this upset of his life, and aggravation of distress, we are to suppose our prodigal almost driven to desperation. Now, for the first time, he feels the severe effects of pinching cold and griping hunger. At this melancholy season, reflection finds a passage to his heart, and he now revolves in his mind the folly and sinfulness of his past life;—considers within himself how idly he has wasted the substance he is at present in the utmost need of;—looks back with shame on the iniquity of his actions, and forward with horror on the rueful scene of misery that awaits him; until his brain, torn with excruciating thought, loses at once its power of thinking, and falls a sacrifice to merciless despair.

Mr. Ireland remarks, on the plate before us:—"Our improvident spendthrift is now lodged in that dreary receptacle of human misery,—a prison. His countenance exhibits a picture of despair; the forlorn state of his mind is displayed in every limb, and his exhausted finances, by the turnkey's demand of prison fees, not being answered, and the boy refusing to leave a tankard of porter, unless he is paid for it.

"We see by the enraged countenance of his wife, that she is violently reproaching him for having deceived and ruined her. To crown this catalogue of human tortures, the poor girl whom he deserted, is come with her child—perhaps to comfort him,—to alleviate his sorrows, to soothe his sufferings:—but the agonising view is too much for her agitated frame; shocked at the prospect of that misery which she cannot remove, every object swims before her eyes,—a film covers the sight,—the blood forsakes her cheeks—her lips assume a pallid hue,—and she sinks to the floor of the prison in temporary death. What a heart-rending prospect for him by whom this is occasioned!

"The wretched, squalid inmate, who is assisting the fainting female, bears every mark of being naturalised to the place; out of his pocket hangs a scroll, on which is inscribed, 'A scheme to pay the National Debt, by J. L. now a prisoner in the Fleet.' So attentive was this poor gentleman to the debts of the nation, that he totally forgot his own. The cries of the child, and the good-natured attentions of the women, heighten the interest, and realise the scene. Over the group are a large pair of wings, with which some emulator of Dedalus intended to escape from his confinement; but finding them inadequate to the execution of his project, has placed them upon the tester of his bed. They would not exalt him to the regions of air, but they o'ercanopy him on earth. A chemist in the back-ground, happy in his views, watching the moment of projection, is not to be disturbed from his dream by any thing less than the fall of the roof, or the bursting of his retort;—and if his dream affords him felicity, why should he be awakened? The bed and gridiron, those poor remnants of our miserable spendthrift's wretched property, are brought here as necessary in his degraded situation; on one he must try to repose his wearied frame, on the other, he is to dress his scanty meal."

THE RAKE'S PROGRESS.

THE RAKE'S PROGRESS.