Concerning the dance as a means of social intercourse, it does not appear to have been formulated as an accomplishment until late in the thirteenth century, and at a later date was cultivated as a means of teaching what we call deportment, until it became almost a necessity with the classes, as is shown by the literature of that period. The various social dances, such as the Volte, the Jig and the Galliard, although in early periods, not so numerous, required a certain training and agility. These, however, soon became complicated with many social and local variations, the characteristics of which are a study in themselves. The dances (figs. 37 and 38) in a field of sports, from an Italian engraving of the fifteenth century, show us nothing new; indeed, with different costumes it is very like what we have from Egypt (fig. 3), only a different phase of the action, and the attitude of this old dance is repeated even to our own time.

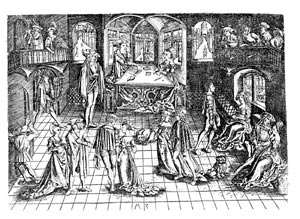

Fig. 39: Chamber dance, 15th century. From a drawing by Martin Zasinger.

In the Chamber dance by Martin Zasinger (fig. 39), of the fifteenth century, no figures are in action, but we see an arrangement of the guests and musicians, from which it is evident that the Chamber dance as a social function had progressed and that the "Bal paré," etc., was here in embryo.

The flute and viol are evidently opening the function and the trumpets and other portions of the orchestra on the other side waiting to come in.

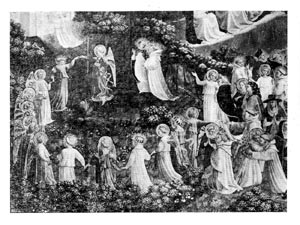

The stately out-door function, in a pleasure garden, from the "Roman de la Rose" (fig. 40) illustrates but one portion of the feature of a dance, another of which is described in Chaucer's translation:

"They threw y fere

Ther mouthes so that through their play

It seemed as they kyste alway."

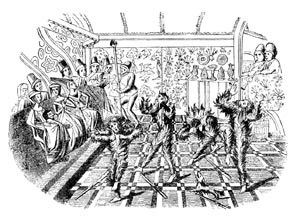

Fancy dress and comic dances have handed down the same characteristics almost to our own time. The Wildeman costume dance (fig. 41) is interesting in many respects, it not only shows us the dance, but the costume and general method of the Chamber.

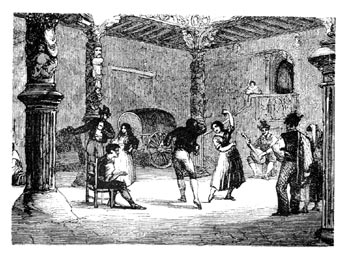

The fifteenth century comic dancers in a fête champétre (fig. 42) and those of the seventeenth century by Callot (fig. 52) are good examples of this entertainment—in the background of the latter a minuet seems to be in progress. The Morris dance (fig. 50) shows us the development that had taken place since the fourteenth century.

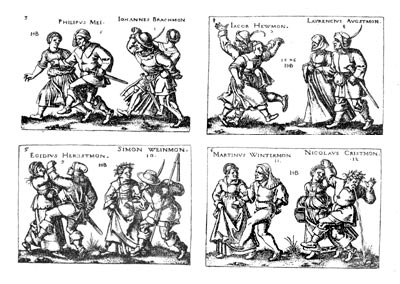

Allusion has already been made to the beautiful paintings of Botticelli and Fra Angelico, which tell us of Italian choral dances of their period; these do not belong to social functions, but are certainly illustrative of the custom of their day. Albert Dürer (figs. 45, 46) has given us illustrations of the field dances of his period, but both these dances and those drawn by Sebald Beham (fig. 47) are coarse, and contrast unfavourably with the Italian, although the action is vigorous and robust.

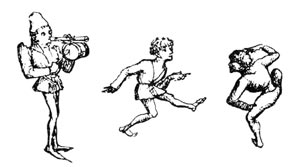

At the end of the sixteenth century we get a work on dancing which shows us completely its position as a social art in that day. It is the "Orchésographie" of Thoinot Arbeau (Jean Tabouret, Canon of Langres, in 1588), from which comes the illustration of the "Galliarde" (fig. 49) and to which I would refer the reader for all the information he desires concerning this period. In this work much stress is laid on the value of learning to dance from many points of view—development of strength, manner, habits and courtesy, etc. Alas! we know now that all these external habits can be acquired and leave the "natural man" beneath.

Desirable, therefore, as good manners and such like are, they do not fulfil all the requirements that the worthy Canon wished to be involved by them.[1]

We have have seen from the fourteenth century (figs. 35 C, 36 A, 46) how common the bagpipe was in out-of-door dances; in the illustrations from Dürer (fig. 46) and in fig. 53 from Holtzer it has developed, and has two accessory pipes, besides that played by the mouth, and the player is accompanied by a sort of clarionet. This also appears to be the only accompaniment of the Trio (fig. 58).

n the sixteenth century certain Spanish dances were introduced into France, such as la Pavane, which was accompanied by hautboys and sackbuts.

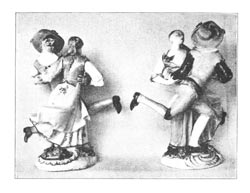

There were, however, various other dances of a number too considerable to describe here, also introduced. The dance of the eighteenth century from Derby ware (fig. 59) seems to be but a continuation in action of those of the sixteenth century, as out-of-door performances.

We have now arrived at the modern style of ball, so beloved by many of the French Monarchs. Henry IV. and Napoleon were fond of giving these in grand style, and in some sort of grand style they persist even as a great social function to our own time. The Court balls of Louis XIII. and XIV. at Versailles were really gorgeous ballets, and their grandeur was astonishing; this custom was continued under the succeeding monarchs. An illustration of one in the eighteenth century by August de l'Aubin (fig. 54) sufficiently shows their character. There is nothing new in the postures illustrated, which may have originated thousands of years ago. As illustrating the popular ball of the period, the design by Hogarth (fig. 55) is an excellent contrast. The contredanse represented was originally the old country dance exported to France and returned with certain arrangements added. This is a topic we need not pursue farther, as almost every reader knows what social dancing now is.

Footnote 1: The advice which he gives is valuable from its bearing on the customs of the 16th century. It even has great historical value, indicating the influence dancing has had on good manners. That the history of dancing is the history of manners may be too much insisted upon. For these reasons we insert these little known passages. The first has reference to the right way of proceeding at a ball.

"Having entered the place where the company is gathered for the dance, choose a good young lady (honneste damoiselle) and raising your hat or bonnet with your right hand you will conduct her to the ball with your left. She, wise and well trained, will tender her left and rise to follow you. Then in the sight of all you conduct her to the end of the room, and you will request the players of instruments to strike up a 'basse danse'; because otherwise through inadvertance they might strike up some other kind of dance. And when they commence to play you must commence to dance. And be careful, that they understand, in your asking for a 'basse danse,' you desire a regular and usual one. Nevertheless, if the air of one song on which* the 'basse danse' is formed pleases you more than another you can give the beginning of the strain to them."

"Capriol:—If the lady refuses, I shall feel very ashamed.

"Arbeau:—A well-trained lady never refuses him who so honours her as to lead her to the dance.

"Capriol:—I think so too, but in the meantime the shame of the refusal remains with me.

"Arbeau:—If you feel sure of another lady's graciousness, take her and leave aside this graceless one, asking her to excuse you for having been importunate; nevertheless, there are those who would not bear it so patiently. But it is better to speak thus than with bitterness, because in so doing you acquire a reputation for being gentle and humane, and to her will fall the character of a 'glorieuse' unworthy of the attention paid her."

"When the instrument player has ceased" continues our good Canon "make a deep bow by way of taking leave of the young lady and conduct her gently to the place whence you took her, whilst thanking her for the honour she has done you." Another extract is not wanting in flavour: "Hold the head and body straight, have a countenance of assurance, spit and cough little, and if necessity compels you, turn your face the other side and use a beautiful white handkerchief. Talk graciously, in gentle and honest speech, neither letting your hands hang as if dead or too full of gesticulation. Be dressed cleanly and neatly 'avec la chausse bien tirée et Pescarpin propre.'

"And bear in mind these particulars."