The paintings of the catacombs date from the third and fourth centuries after Christ. The catacombs, or burial-places of the early Christians, consist of long, narrow, subterranean passages, cut with regularity, and crossing each other like streets in a city. The graves are in the sides of these passages, and there are some larger rooms or chambers into which the narrow passages run. There are about sixty of the catacombs in and near Rome; they are generally called by the name of some saint who is buried in them. The paintings are in the chambers, of which there are sometimes several quite near each other. The reason for their being in these underground places was that Christians were so persecuted under the Romans, that they were obliged to do secretly all that they did as Christians, so that no attention should be attracted to them.

The principal characteristics of these pictures are a simple majesty and earnestness of effect; perhaps spirituality is the word to use, for by these paintings the early Christians desired to express their belief in the religion of Christ, and especially in the immortality of the soul, which was a very precious doctrine to them. The catacombs of Rome were more numerous and important than those of any other city.

Many of the paintings in the catacombs had a symbolic meaning, beyond the plainer intention which appeared at the first sight of them: you will know what I mean when I say that not only was this picture of Moses striking the rock intended to represent an historical fact in the life of Moses, but the flowing water was also regarded as a type of the blessing of Christian baptism.

Fig. 17.—Moses. From a painting in the Catacomb of S. Agnes.

Fig. 17.—Moses. From a painting in the Catacomb of S. Agnes.

Fig. 18.—decoration of a Roof.

Fig. 18.—decoration of a Roof.The walls of the chambers of the catacombs are laid out in such a manner as to have the effect of decorated apartments, just as was done in the pagan tombs, and sometimes the pictures were a strange union of pagan and Christian devices.

The above cut, from the Catacomb of S. Domitilla, has in the centre the pagan god Orpheus playing his lyre, while in the alternate compartments of the border are the following Christian subjects: 1, David with the Sling; 2, Moses Striking the Rock; 3, Daniel in the Lion’s Den; 4, The Raising of Lazarus. The other small divisions have pictures of sacrificial animals. These two cuts will give you an idea of the catacomb wall-paintings.

The mosaics of the Middle Ages were of a purely ornamental character down to the time of Constantine. Then, when the protection of a Christian emperor enabled the Christians to express themselves without fear, the doctrines of the church and the stories of the life of Christ and the histories of the saints, as well as many other instructive religious subjects, were made in mosaics, and placed in prominent places in churches and basilicas. Mosaics are very durable, and many belonging to the early Christian era still remain.

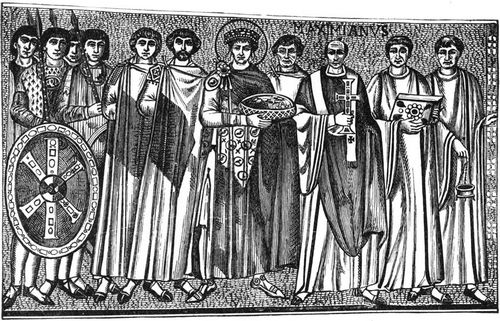

The mosaics at Ravenna form the most connected series, and are the best preserved of those that still exist. While it is true in a certain sense that Rome was always the art centre of Italy, it is also true that at Ravenna the works of art have not suffered from devastation and restoration as have those of Rome. After the invasion of the Visigoths in A.D. 404, Honorius transferred the imperial court to Ravenna, and that city then became distinguished for its learning and art. The Ravenna mosaics are so numerous that I shall only speak of one series, from which I give an illustration (Fig. 19).

This mosaic is in the church of S. Vitalis, which was built between a.d. 526 and 547. In the dome of the church there is a grand representation of Christ enthroned; below Him are the sacred rivers of Paradise; near Him are two angels and S. Vitalis, to whom the Saviour is presenting a crown; Bishop Ecclesius, the founder of the church, is also represented near by with a model of the church in his hand.

On a lower wall there are two pictures in which the Emperor Justinian and the Empress Theodosia are represented: our cut is from one of these, and shows the emperor and empress in magnificent costumes, each followed by a train of attendants. This emperor never visited Ravenna; but he sent such rich gifts to this church that he and his wife are represented as its donors.

Fig. 19.—Justinian, Theodora, and Attendants. From a mosaic picture at S. Vitalis, Ravenna.

Fig. 19.—Justinian, Theodora, and Attendants. From a mosaic picture at S. Vitalis, Ravenna.After the time of Justinian (a.d. 527-565) mosaics began to be less artistic, and those of the later time degenerated, as did everything else during the Middle or Dark Ages, and at last all works of art show less and less of the Greek or Classic influence.

When we use the word miniature as an art term, it does not mean simply a small picture as it does in ordinary conversation; it means the pictures executed by the hand of an illuminator or miniator of manuscripts, and he is so called from the minium or cinnabar which he used in making colors.

In the days of antiquity, as I have told you in speaking of Egypt, it was customary to illustrate manuscripts, and during the Middle Ages this art was very extensively practised. Many monks spent their whole lives in illuminating religious books, and in Constantinople and other eastern cities this art reached a high degree of perfection. Some manuscripts have simple borders and colored initial letters only; sometimes but a single color is used, and is generally red, from which comes our word rubric, which means any writing or printing in red ink, and is derived from the Latin rubrum, or red. This was the origin of illumination or miniature-painting, which went on from one step to another until, at its highest state, most beautiful pictures were painted in manuscripts in which rich colors were used on gold or silver backgrounds, and the effect of the whole was as rich and ornamental as it is possible to imagine.

Many of these old manuscripts are seen in museums, libraries, and various collections; they are very precious and costly, as well as interesting; their study is fascinating, for almost every one of the numberless designs that are used in them has its own symbolic meaning. The most ancient, artistic miniatures of which we know are those on a manuscript of a part of the book of Genesis; it is in the Imperial Library at Vienna, and was made at the end of the fifth century. In the same collection there is a very extraordinary manuscript, from which I give an illustration.

This manuscript is a treatise on botany, and was written by Dioskorides for his pupil, the Princess Juliana Anicia, a granddaughter of the Emperor Valentine III. As this princess died at Constantinople a.d. 527, this manuscript dates from the beginning of the sixth century. This picture from it represents Dioskorides dressed in white robes and seated in a chair of gold; before him stands a woman in a gold tunic and scarlet mantle, who represents the genius of discovery; she presents the legendary mandrake root, or mandragora, to the learned man, while between them is the dog that has pulled the root, and falls dead, according to the fabulous story. This manuscript was painted by a masterly hand, and is curious and interesting; the plants, snakes, birds, and insects must have been painted from nature, and the whole is most skilfully done.

Fig. 20.—The Discovery of the Herb Mandragora.From a MS. of Dioskorides, at Vienna.

Fig. 20.—The Discovery of the Herb Mandragora.From a MS. of Dioskorides, at Vienna.During the Middle Ages the arts as practised in Rome were carried into all the different countries in which the Romans made conquests or sent their monks and missionaries to establish churches, convents, and schools. Thus the mediæval arts were practised in Gaul, Spain, Germany, and Great Britain. No wall-paintings or mosaics remain from the early German or Celtic peoples; but their illuminated manuscripts are very numerous: miniature-painting was extensively done in Ireland, and many Irish manuscripts remain in the collections of Great Britain.

When Charlemagne became the king of the Franks in 768, there was little knowledge of any art among his northern subjects; in 800 he made himself emperor of the Romans, also, and when the Franks saw all the splendor of Rome and other parts of Italy, it was not difficult for the great emperor to introduce the arts into the Frankish portion of his empire. All sorts of beautiful objects were carried from Italy by the Franks, and great workshops were established at Aix-la-Chapelle, the capital, and were placed under the care of Eginhard, who was skilled in bronze-casting, modelling, and other arts; he was called Bezaleel, after the builder of the Tabernacle. We have many accounts of the wall-paintings and mosaics of the Franks; but there are no remains of them that can be identified with positive accuracy.

Miniature-painting flourished under the rule of Charlemagne and his family, and reached a point of great magnificence in effect, though it was never as artistic as the work of the Italian miniators; and, indeed, gradually everything connected with art was declining in all parts of the world; and as we study its history, we can understand why the terms Dark Ages and Middle Ages are used to denote the same epoch, remarkable as it is for the decay and extinction of so many beautiful things.