One of the most important nations of antiquity was the Etruscan, inhabiting, according to some authorities, a dominion from Lombardy to the Alps, and from the Mediterranean to the Adriatic.

Etruria gave a dynasty to Rome in Servius Tullius, who originally was Masterna, an Etruscan.

It is, however, with the dancing that we are dealing. There is little doubt that they were dancers in every sense; there are many ancient sepulchres in Etruria, with dancing painted on their walls. Other description than that of the pictures we do not possess, for as yet the language is a dead letter. There is no doubt, as Gerhardt [1] suggests, that they considered dancing as one of the emblems of joy in a future state, and that the dead were received with dancing and music in their new home. They danced to the music of the pipes, the lyre, the castanets of wood, steel, or brass, as is shown in the illustrations taken from the monuments.

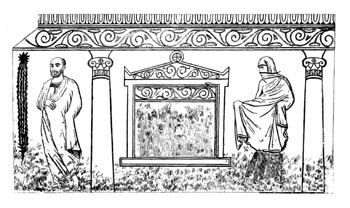

That the Phoenicians and Greeks had at certain times immense influence on the Etruscans is evident from their relics which we possess (fig. 20).

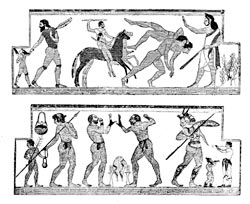

A characteristic illustration of the dancer is from a painting in the tomb of the Vasi dipinti, Corneto, which, according to Mr. Dennis, [2] belongs to the archaic period, and is perhaps as early as 600 B.C. It exhibits a stronger Greek influence than some of the paintings. Fig. 21, showing a military dance to pipes, with other sports, comes from the Grotta della Scimia, also at Corneto; these show a more purely Etruscan character.

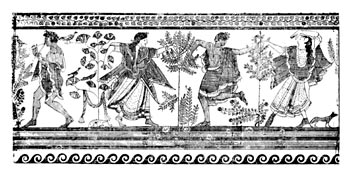

The pretty dancing scene from the Grotta del Triclinio at Corneto is taken from a full-sized copy in the British Museum, and is of the greatest interest. It is considered to be of the Greco-Etruscan period, and later than the previous examples (fig. 22).

There is a peculiarity in the attitude of the hands, and of the fingers being kept flat and close together; it is not a little curious that the modern Japanese dance, as exhibited by Mme. Sadi Yacca, has this peculiarity, whether the result of ancient tradition or of modern revival, the writer cannot say.

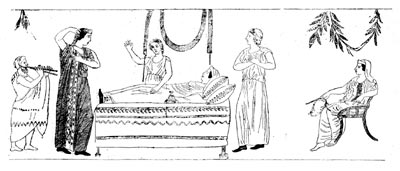

Almost as interesting as the Etruscan are the illustrations of dancing found in the painted tombs of the Campagna and Southern Italy, once part of "Magna Grecia"; the figure of a funeral dance, with the double pipe accompaniments, from a painted tomb near Albanella (fig. 23) may be as late as 300 B.C., and those in figs. 24, 25 from a tomb near Capua are probably of about the same period. These Samnite dances appear essentially different from the Etruscan; although both Greek and Etruscan influence are very evident, they are more solemn and stately. This may, however, arise from a different national custom.

That the Etruscan, Sabellian, Oscan, Samnite, and other national dances of the country had some influence on the art in Rome is highly probable, but the paucity of early Roman examples renders the evidence difficult.

Rome as a conquering imperial power represented nearly the whole world of its day, and its dances accordingly were most numerous. Amongst the illustrations already given we have many that were preserved in Rome. In the beginning of its existence as a power only religious dances were practised, and many of these were of Etruscan origin, such as the Lupercalia, the Ambarvalia, &c. In the former the dancers were demi-nude, and probably originally shepherds; the latter was a serious dancing procession through fields and villages.

A great dance of a severe kind was executed by the Salii, priests of Mars, an ecclesiastical corporation of twelve chosen patricians. In their procession and dance, on March 1, and succeeding days, carrying the Ancilia, they sang songs and hymns, and afterwards retired to a great banquet in the Temple of Mars. That the practice was originally Etruscan may be gathered from the circumstance that on a gem showing the armed priests carrying the shields there are Etruscan letters. There were also an order of female Salii. Another military dance was the Saltatio bellicrepa, said to have been instituted by Romulus in commemoration of the Rape of the Sabines.

The Pyrrhic dance (fig. 13) was also introduced into Rome by Julius Caesar, and was danced by the children of the leading men of Asia and Bithynia.

As, however, the State increased in power by conquest, it absorbed with other countries other habits, and the art degenerated often, like that of Greece and Etruria, into a vehicle for orgies, when they brought to Rome with their Asiatic captives even more licentious practices and dances.

As Rome, which never rose to the intellectual and imaginative state of Greece in her best period, represented wealth, commerce, and conquest, in a greater degree, so were her arts, and with these the lyric. In her best state her nobles danced, Appius Claudius excelled, and Sallust tells us that Sempronia "psaltere saltare elegantius"; so that in those days ladies played and danced, but no Roman citizen danced except in the religious dances. They carried mimetic dances to a very perfect character in the time of Augustus under the term of Musica muta. After the second Punic war, as Greek habits made their way into Italy, it became a fashion for the young to learn to dance. The education in dancing and gesture were important in the actor, as masks prevented any display of feature. The position of the actor was never recognized professionally, and was considered infamia. But the change came, which caused Cicero to say "no one danced when sober." Eventually the performers of lower class occupied the dancing platform, and Herculaneum and Pompeii have shown us the results.

In the theatre the method of the Roman chorus differed from that of the Greeks. In the latter the orchestra or place for the dancing and chorus was about 12 ft. below the stage, with steps to ascend when these were required; in the former the chorus was not used in comedy, and having no orchestra was in tragedies placed upon the stage. The getting together of the chorus was a public service, or liturgia, and in the early days of Grecian prosperity was provided by the choregus.

Tiberius by a decree abolished the Saturnalia, and exiled the dancing teachers, but the many acts of the Senate to secure a better standard were useless against the foreign inhabitants of the Empire accustomed to sensuality and licence.

Perhaps the encouragement of the more brutal combats of the Coliseum did something to suppress the more delicate arts, but historians have told us, and it is common knowledge, what became of the great Empire, and the lyric with other arts were destroyed by licentious preferences.

Footnote 1: "Ann. Institut.": 1831, p. 321.

Footnote 2:"Etruria," vol. i., p. 380.