Books Recommended: Colvin, A. Durer, his Teachers, his Rivals, and his Scholars; Eye, Leben und Werke Albrecht Durers; Förster, Peter von Cornelius; Förster, Geschichte der Deutschen Kunst; Keane, Early Teutonic, Italian, and French Painters; Kügler, Handbook to German and Netherland Schools, trans. by Crowe; Merlo, Die Meister der altkolnischer Malerschule; Moore, Albert Durer; Pecht, Deutsche Kunstler des Neunzehnten Jahrhunderts; Reber, Geschichte der neueren Deutschen Kunst; Riegel, Deutsche Kunststudien; Rosenberg, Die Berliner Malerschule; Rosenberg,Sebald und Barthel Beham; Rumohr, Hans Holbein der Jungere; Sandrart, Teutsche Akademie der Edlen Bau, Bild-und Malerey-Kunste; Schuchardt, Lucas Cranach's Leben; Thausig, Albert Durer, His Life and Works; Waagen, Kunstwerke und Kunstler in Deutschland; E. aus'm Weerth, Wandmalereien des Mittelalters in den Rheinlanden; Wessely, Adolph Menzel; Woltmann, Holbein and his Time; Woltmann, Geschichte der Deutschen Kunst im Elsass; Wurtzbach, Martin Schongauer.

EARLY GERMAN PAINTING: The Teutonic lands, like almost all of the countries of Europe, received their first art impulse from Christianity through Italy. The centre of the faith was at Rome, and from there the influence in art spread west and north, and in each land it was modified by local peculiarities of type and temperament. In Germany, even in the early days, though Christianity was the theme of early illuminations, miniatures, and the like, and though there was a traditional form reaching back to Italy and Byzantium, yet under it was the Teutonic type—the material, awkward, rather coarse Germanic point of view. The wish to realize native surroundings was apparent from the beginning.

It is probable that the earliest painting in Germany took the form of illuminations. At what date it first appeared is unknown. In wall-painting a poor quality of work was executed in the churches as early as the ninth century, and probably earlier. The oldest now extant are those at Oberzell, dating back to the last part of the tenth century. Better examples are seen in the Lower Church of Schwarzrheindorf, of the twelfth century, and still better in the choir and transept of the Brunswick cathedral, ascribed to the early thirteenth century.

All of these works have an archaic appearance about them, but they are better in composition and drawing than the productions of Italy and Byzantium at that time. It is likely that all the German churches at this time were decorated, but most of the paintings have been destroyed. The usual method was to cover the walls and wooden ceilings with blue grounds, and upon these to place figures surrounded by architectural ornaments. Stained glass was also used extensively. Panel painting seems to have come into existence before the thirteenth century (whether developed from miniature or wall-painting is unknown), and was used for altar decorations. The panels were done in tempera with figures in light colors upon gold grounds. The spirituality of the age with a mingling of northern sentiment appeared in the figure. This figure was at times graceful, and again awkward and archaic, according to the place of production and the influence of either France or Italy. The oldest panels extant are from the Wiesenkirche at Soest, now in the Berlin Museum. They do not date before the thirteenth century.

FOURTEENTH AND FIFTEENTH CENTURIES: In the fourteenth century the influence of France began to show strongly in willowy figures, long flowing draperies, and sentimental poses. The artists along the Rhine showed this more than those in the provinces to the east, where a ruder if freer art appeared. The best panel-painting of the time was done at Cologne, where we meet with the name of the first painter, Meister Wilhelm, and where a school was established usually known as the

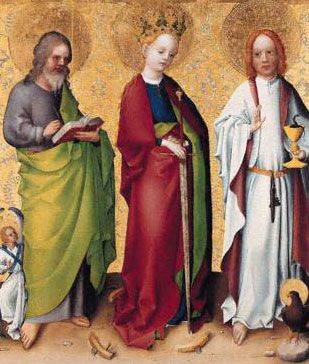

SCHOOL OF COLOGNE: This school probably got its sentimental inclination, shown in slight forms and tender expression, from France, but derived much of its technic from the Netherlands. Stephen Lochner, or Meister Stephen, (fl. 1450) leaned toward the Flemish methods, and in his celebrated picture, the Madonna of the Rose Garden, in the Cologne Museum, there is an indication of this; but there is also an individuality showing the growth of German independence in painting. The figures of his Dombild have little manliness or power, but considerable grace, pathos, and religious feeling. They are not abstract types but the spiritualized people of the country in native costumes, with much gold, jewelry, and armor. Gold was used instead of a landscape background, and the foreground was spattered with flowers and leaves. The outlines are rather hard, and none of the aërial perspective of the Flemings is given. After a time French sentiment was still further encroached upon by Flemish realism, as shown in the works of the Master of the Lyversberg Passion (fl. about 1463-1480), to be seen in the Cologne Museum.

BOHEMIAN SCHOOL: It was not on the Lower Rhine alone that German painting was practised. The Bohemian school, located near Prague, flourished for a short time in the fourteenth century, under Charles IV., with Theodorich of Prague (fl. 1348-1378), Wurmser, and Kunz, as the chief masters. Their art was quite the reverse of the Cologne painters. It was heavy, clumsy, bony, awkward. If more original it was less graceful, not so pathetic, not so religious. Sentiment was slurred through a harsh attempt at realism, and the religious subject met with something of a check in the romantic mediæval chivalric theme, painted quite as often on the castle wall as the scriptural theme on the church wall. After the close of the fourteenth century wall-painting began to die out in favor of panel pictures.

NUREMBERG SCHOOL: Half-way between the sentiment of Cologne and the realism of Prague stood the early school of Nuremberg, with no known painter at its head. Its chief work, the Imhof altar-piece, shows, however, that the Nuremberg masters of the early and middle fifteenth century were between eastern and western influences. They inclined to the graceful swaying figure, following more the sculpture of the time than the Cologne type.

FIFTEENTH AND SIXTEENTH CENTURIES: German art, if begun in the fourteenth century, hardly showed any depth or breadth until the fifteenth century, and no real individual strength until the sixteenth century. It lagged behind the other countries of Europe and produced the cramped archaic altar-piece. Then when printing was invented the painter-engraver came into existence. He was a man who painted panels, but found his largest audience through the circulation of engravings. The two kinds of arts being produced by the one man led to much detailed line work with the brush. Engraving is an influence to be borne in mind in examining the painting of this period.

FIG. 89.—DÜRER. PRAYING VIRGIN. AUGSBURG.

FIG. 89.—DÜRER. PRAYING VIRGIN. AUGSBURG.FRANCONIAN SCHOOL: Nuremberg was the centre of this school, and its most famous early master was Wolgemut (1434-1519), though Plydenwurff is the first-named painter. After the latter's death Wolgemut married his widow and became the head of the school. His paintings were chiefly altar-pieces, in which the figures were rather lank and narrow-shouldered, with sharp outlines, indicative perhaps of the influence of wood-engraving, in which he was much interested. There was, however, in his work an advance in characterization, nobility of expression, and quiet dignity, and it was his good fortune to be the master of one of the most thoroughly original painters of all the German schools—Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528).

With Dürer and Holbein German art reached its apogee in the first half of the sixteenth century, yet their work was not different in spirit from that of their predecessors. Painting simply developed and became forceful and expressive technically without abandoning its early character. There is in Dürer a naive awkwardness of figure, some angularity of line, strain of pose, and in composition oftentimes huddling and overloading of the scene with details. There is not that largeness which seemed native to his Italian contemporaries. He was hampered by that German exactness, which found its best expression in engraving, and which, though unsuited to painting, nevertheless crept into it. Within these limitations Dürer produced the typical art of Germany in the Renaissance time—an art more attractive for the charm and beauty of its parts than for its unity, or its general impression. Dürer was a travelled man, visited Italy and the Netherlands, and, though he always remained a German in art, yet he picked up some Italian methods from Bellini and Mantegna that are faintly apparent in some of his works. In subject he was almost exclusively religious, painting the altar-piece with infinite care upon wooden panel, canvas, or parchment. He never worked in fresco, preferring oil and tempera. In drawing he was often harsh and faulty, in draperies cramped at times, and then, again, as in the Apostle panels at Munich, very broad, and effective. Many of his pictures show a hard, dry brush, and a few, again, are so free and mellow that they look as though done by another hand. He was usually minute in detail, especially in such features as hair, cloth, flesh. His portraits were uneven and not his best productions. He was too close a scrutinizer of the part and not enough of an observer of the whole for good portraiture. Indeed, that is the criticism to be made upon all his work. He was an exquisite realist of certain features, but not always of the ensemble. Nevertheless he holds first rank in the German art of the Renaissance, not only on account of his technical ability, but also because of his imagination, sincerity, and striking originality.

Dürer's influence was wide-spread throughout Germany, especially in engraving, of which he was a master. In painting Schäufelin (1490?-1540?) was probably his apprentice, and in his work followed the master so closely that many of his works have been attributed to Dürer. This is true in measure of Hans Baldung (1476?-1552?). Hans von Kulmbach (?-1522) was a painter of more than ordinary importance, brilliant in coloring, a follower of Dürer, who was inclined toward Italian methods, an inclination that afterward developed all through German art. Following Dürer's formulas came a large number of so-called "Little Masters" (from the size of their engraved plates), who were more engravers than painters. Among the more important of those who were painters as well as engravers were Altdorfer(1480?-1538), a rival rather than an imitator of Dürer; Barthel Beham (1502-1540), Sebald Beham (1500-1550), Pencz (1500?-1550), Aldegrever (1502-1558), and Bink (1490?-1569?).

SWABIAN SCHOOL: This school includes a number of painters who were located at different places, like Colmar and Ulm, and later on it included the Holbeins at Augsburg, who were really the consummation of the school. In the fifteenth century one of the early leaders was Martin Schöngauer (1446?-1488), at Colmar. He is supposed to have been a pupil of Roger Van der Weyden, of the Flemish school, and is better known by his engravings than his paintings, none of the latter being positively authenticated. He was thoroughly German in his type and treatment, though, perhaps, indebted to the Flemings for his coloring. There was some angularity in his figures and draperies, and a tendency to get nearer nature and further away from the ecclesiastical and ascetic conception in all that he did.

At Ulm a local school came into existence with Zeitblom (fl. 1484-1517), who was probably a pupil of Schüchlin. He had neither Schöngauer's force nor his fancy, but was a simple, straightforward painter of one rather strong type. His drawing was not good, except in the draperies, but he was quite remarkable for the solidity and substance of his painting, considering the age he lived in was given to hard, thin brush-work. Schaffner (fl. 1500-1535) was another Ulm painter, a junior to Zeitblom, of whom little is known, save from a few pictures graceful and free in composition. A recently discovered man, Bernard Strigel (1461?-1528?) seems to have been excellent in portraiture.

FIG. 91.—PILOTY. WISE AND FOOLISH VIRGINS.

FIG. 91.—PILOTY. WISE AND FOOLISH VIRGINS.At Augsburg there was still another school, which came into prominence in the sixteenth century with Burkmair and the Holbeins. It was only a part of the Swabian school, a concentration of artistic force about Augsburg, which, toward the close of the fifteenth century, had come into competition with Nuremberg, and rather outranked it in splendor. It was at Augsburg that the Renaissance art in Germany showed in more restful composition, less angularity, better modelling and painting, and more sense of the ensemble of a picture. Hans Burkmair (1473-1531) was the founder of the school, a pupil of Schöngauer, later influenced by Dürer, and finally showing the influence of Italian art. He was not, like Dürer, a religious painter, though doing religious subjects. He was more concerned with worldly appearance, of which he had a large knowledge, as may be seen from his illustrations for engraving. As a painter he was a rather fine colorist, indulging in the fantastic of architecture but with good taste, crude in drawing but forceful, and at times giving excellent effects of motion. He was rounder, fuller, calmer in composition than Dürer, but never so strong an artist.

Next to Burkmair comes the celebrated Holbein family. There were four of them all told, but only two of them, Hans the Elder and Hans the Younger, need be mentioned. Holbein the Elder (1460?-1524), after Burkmair, was the best painter of his time and school without being in himself a great artist. Schöngauer was at first his guide, though he soon submitted to some Flemish and Cologne influence, and later on followed Italian form and method in composition to some extent. He was a good draughtsman, and very clever at catching realistic points of physiognomy—a gift he left his son Hans. In addition he had some feeling for architecture and ornament, and in handling was a bit hard, and oftentimes careless. The best half of his life fell in the latter part of the fifteenth century, and he never achieved the free painter's quality of his son.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543) holds, with Dürer, the high place in German art. He was a more mature painter than Dürer, coming as he did a quarter of a century later. He was the Renaissance artist of Germany, whereas Dürer always had a little of the Gothic clinging to him. The two men were widely different in their points of view and in their work. Dürer was an idealist seeking after a type, a religious painter, a painter of panels with the spirit of an engraver. Holbein was emphatically a realist finding material in the actual life about him, a designer of cartoons and large wall paintings in something of the Italian spirit, a man who painted religious themes but with little spiritual significance.

It is probable that he got his first instruction from his father and from Burkmair. He was an infant prodigy, developed early, saw much foreign art, and showed a number of tendencies in his work. In composition and drawing he appeared at times to be following Mantegna and the northern Italians; in brush-work he resembled the Flemings, especially Massys; yet he was never an imitator of either Italian or Flemish painting. Decidedly a self-sufficient and an observing man, he travelled in Italy and the Netherlands, and spent much of his life in England, where he met with great success at court as a portrait-painter. From seeing much he assimilated much, yet always remained German, changing his style but little as he grew older. His wall paintings have perished, but the drawings from them are preserved and show him as an artist of much invention. He is now known chiefly by his portraits, of which there are many of great excellence. His facility in grasping physiognomy and realizing character, the quiet dignity of his composition, his firm modelling, clear outline, harmonious coloring, excellent detail, and easy solid painting, all place him in the front rank of great painters. That he was not always bound down to literal facts may be seen in his many designs for wood-engravings. His portrait of Hubert Morett, in the Dresden Gallery, shows his art to advantage, and there are many portraits by him of great spirit in England, in the Louvre, and elsewhere.

SAXON SCHOOL: Lucas Cranach (1472-1553) was a Franconian master, who settled in Saxony and was successively court-painter to three Electors and the leader of a small local school there. He, perhaps, studied under Grünewald, but was so positive a character that he showed no strong school influence. His work was fantastic, odd in conception and execution, sometimes ludicrous, and always archaic-looking. His type was rather strained in proportions, not always well drawn, but graceful even when not truthful. This type was carried into all his works, and finally became a mannerism with him. In subject he was religious, mythological, romantic, pastoral, with a preference for the nude figure. In coloring he was at first golden, then brown, and finally cold and sombre. The lack of aërial perspective and shadow masses gave his work a queer look, and he was never much of a brushman. His pictures were typical of the time and country, and for that and for their strong individuality they are ranked among the most interesting paintings of the German school. Perhaps his most satisfactory works are his portraits. Lucas Cranach the Younger (1515-1586) was the best of the elder Cranach's pupils. Many of his pictures are attributed to his father. He followed the elder closely, but was a weaker man, with a smoother brush and a more rosy color. Though there were many pupils the school did not go beyond the Cranach family. It began with the father and died with the son.

SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES: These were unrelieved centuries of decline in German painting. After Dürer, Holbein, and Cranach had passed there came about a senseless imitation of Italy, combined with an equally senseless imitation of detail in nature that produced nothing worthy of the name of original or genuine art. It is not probable that the Reformation had any more to do with this than with the decline in Italy. It was a period of barrenness in both countries. The Italian imitators in Germany were chiefly Rottenhammer (1564-1623), and Elzheimer (1574?-1620). After them came the representative of the other extreme in Denner (1685-1749), who thought to be great in portraiture by the minute imitation of hair, freckles, and three-days'-old beard—a petty and unworthy realism which excited some curiosity but never held rank as art. Mengs (1728-1779) sought for the sublime through eclecticism, but never reached it. His work, though academic and correct, is lacking in spirit and originality. Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807) succeeded in pleasing her inartistic age with the simply pretty, while Carstens (1754-1798) was a conscientious if mistaken student of the great Italians—a man of some severity in form and of academic inclinations.

NINETEENTH CENTURY: In the first part of this century there started in Germany a so-called "revival of art" led by Overbeck (1789-1869), Cornelius (1783-1867), Veit (1793-1877), and Schadow(1789-1862), but like many another revival of art it did not amount to much. The attempt to "revive" the past is usually a failure. The forms are caught, but the spirit is lost. The nineteenth-century attempt in Germany was brought about by the study of monumental painting in Italy, and the taking up of the religious spirit in a pre-Raphaelite manner. Something also of German romanticism was its inspiration. Overbeck remained in Rome, but the others, after some time in Italy, returned to Germany, diffused their teaching, and really formed a new epoch in German painting. A modern art began with ambitions and subjects entirely disproportionate to its skill. The monumental, the ideal, the classic, the exalted, were spread over enormous spaces, but there was no reason for such work in the contemporary German life, and nothing to warrant its appearance save that its better had appeared in Italy during the Renaissance. Cornelius after his return became the head of the

MUNICH SCHOOL and painted pictures of the heroes of the classic and the Christian world upon a large scale. Nothing but their size and good intention ever brought them into notice, for their form and coloring were both commonplace. Schnorr (1794-1872) followed in the same style with the Niebelungen Lied, Charlemagne, and Barbarossa for subjects. Kaulbach (1805-1874) was a pupil of Cornelius, and had some ability but little taste, and not enough originality to produce great art. Piloty (1826-1886) was more realistic, more of a painter and ranks as one of the best of the early Munich masters. After him Munich art became genre-like in subject, with greater attention given to truthful representation in light, color, texture. To-day there are a large number of painters in the school who are remarkable for realistic detail.

DUSSELDORF SCHOOL: After 1826 this school came into prominence under the guidance of Schadow. It did not fancy monumental painting so much as the common easel picture, with the sentimental, the dramatic, or the romantic subject. It was no better in either form or color than the Munich school, in fact not so good, though there were painters who emanated from it who had ability. At Berlin the inclination was to follow the methods and ideas held at Dusseldorf.

The whole academic tendency of modern painting in Germany and Austria for the past fifty years has not been favorable to the best kind of pictorial art. There is a disposition on the part of artists to tell stories, to encroach upon the sentiment of literature, to paint with a dry brush in harsh unsympathetic colors, to ignore relations of light-and-shade, and to slur beauties of form. The subject seems to count for more than the truth of representation, or the individuality of view. From time to time artists of much ability have appeared, but these form an exception rather than a rule. The men to-day who are the great artists of Germany are less followers of the German tradition than individuals each working in a style peculiar to himself. A few only of them call for mention. Menzel (1815-1905) is easily first, a painter of group pictures, a good colorist, and a powerful pen-and-ink draughtsman; Lenbach (1836-1904), a forceful portraitist; Uhde (1848-), a portrayer of scriptural scenes in modern costumes with much sincerity, good color, and light; Leibl (1844-1900), an artist with something of the Holbein touch and realism; Thoma, a Frankfort painter of decorative friezes and panels; Liebermann, Gotthardt Kuehl, Franz Stuck,Max Klinger, Greiner, Trübner, Bartels, Keller.

FIG. 93.—MENZEL. A READER.

FIG. 93.—MENZEL. A READER.Aside from these men there are several notable painters with German affinities, like Makart (1840-1884), an Austrian, who possessed good technical qualities and indulged in a profusion of color;Munkacsy (1846-1900), a Hungarian, who is perhaps more Parisian than German in technic, and Böcklin (1827-1901), a Swiss, who is quite by himself in fantastic and grotesque subjects, a weird and uncanny imagination, and a brilliant prismatic coloring.

PRINCIPAL WORKS: Bohemian School—Theoderich of Prague, Karlstein chap. and University Library Prague, Vienna Mus.; Wurmser, same places.

Franconian School—Wolgemut, Aschaffenburg, Munich, Nuremberg, Cassel Mus.; Dürer, Crucifixion Dresden, Trinity Vienna Mus., other works Munich, Nuremberg, Madrid Mus.; Schäufelin, Basle, Bamberg, Cassel, Munich, Nuremberg, Nordlingen Mus., and Ulm Cathedral; Baldung, Aschaffenburg, Basle, Berlin, Kunsthalle Carlsruhe, Freiburg Cathedral; Kulmbach, Munich, Nuremberg, Oldenburg;Altdorfer and the "Little Masters" are seen in the Augsburg, Nuremberg, Berlin, Munich and Fürstenberg Mus.

Swabian School—Schöngauer, attributed pictures Colmar Mus.; Zeitblom, Augsburg, Berlin, Carlsruhe, Munich, Nuremberg, Simaringen Mus.; Schaffner, Munich, Schliessheim, Nuremberg, Ulm Cathedral; Strigel, Berlin, Carlsruhe, Munich, Nuremberg; Burkmair, Augsburg, Berlin, Munich, Maurice chap. Nuremberg; Holbein the Elder, Augsburg, Nuremberg, Basle, Städel Mus., Frankfort;Holbein the Younger, Basle, Carlsruhe, Darmstadt, Dresden, Berlin, Louvre, Windsor Castle, Vienna Mus.

Saxon School—Cranach, Bamberg Cathedral and Gallery, Munich, Vienna, Dresden, Berlin, Stuttgart, Cassel; Cranach the Younger, Stadtkirche Wittenberg, Leipsic, Vienna, Nuremberg Mus.

SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY PAINTERS: Rottenhammer, Louvre, Berlin, Munich, Schliessheim, Vienna, Kunsthalle Hamburg; Elzheimer, Stadel, Brunswick, Louvre, Munich, Berlin, Dresden; Denner, Kunsthalle Hamburg, Berlin, Brunswick, Dresden, Vienna, Munich; Mengs, Madrid, Vienna, Dresden, Munich, St. Petersburg; Angelica Kauffman, Vienna, Hermitage, Turin, Dresden, Nat. Gal. Lon., Phila. Acad.

NINETEENTH-CENTURY PAINTERS: Overbeck, frescos in S. Maria degli Angeli Assisi, Villa Massimo Rome, Carlsruhe, New Pinacothek, Munich, Städel Mus., Dusseldorf; Cornelius, frescos Glyptothek and Ludwigkirche Munich, Casa Zuccaro Rome, Royal Cemetery Berlin; Veit, frescos Villa Bartholdi Rome, Städel, Nat. Gal. Berlin; Schadow, Nat. Gal. Berlin, Antwerp, Städel, Munich Mus., frescos Villa Bartholdi Rome; Schnorr, Dresden, Cologne, Carlsruhe, New Pinacothek Munich, Städel Mus.; Kaulbach, wall paintings Berlin Mus., Raczynski Gal. Berlin, New Pinacothek Munich, Stuttgart, Phila. Acad.; Piloty, best pictures in the New Pinacothek and Maximilianeum Munich, Nat. Gal. Berlin; Menzel, Nat. Gal., Raczynski Mus. Berlin, Breslau Mus.; Lenbach, Nat. Gal. Berlin, New Pinacothek Munich, Kunsthalle Hamburg, Zürich Gal.; Uhde, Leipsic Mus.; Leibl, Dresden Mus. The contemporary paintings have not as yet found their way, to any extent, into public museums, but may be seen in the expositions at Berlin and Munich from year to year. Makart has one work in the Metropolitan Mus., N. Y., as has also Munkacsy; other works by them and by Böcklin may be seen in the Nat. Gal. Berlin.