The glory of Parma is the Cathedral, which represents the labors of many centuries. The building itself was begun in 1058, and completed in the thirteenth century. The interior was beautified by a succession of artists, one of whom was our painter Correggio. His work here was the decoration of the cupola, and he began it immediately upon finishing the frescoes in the church of S. Giovanni Evangelista.

The Cathedral dome is octagonal in shape. In the roof, or topmost space, the Virgin Mary seems borne on circling throngs of saints and angels to meet the Saviour in the upper air. Below the dome runs a cornice, or frieze, in eight sections, filled with figures of apostles gazing upon the vision. Still lower are four decorated pendentives, similar to those in the church of S. Giovanni Evangelista. These contain respectively the four patron saints of Parma.

To the spectator looking up from below, the effect is of "a moving vision, rapturous and ecstatic." A multitude of radiant figures sweep and whirl through the heavenly spaces. "They are upon every side, bending, tossing, floating, and diving through the clouds, hovering above the abysmal void that is between the dome and the earth below it."[27] Wonderful indeed is the triumph of the painter's art in this place. "Reverse the cupola and fill it with gold, and even that will not represent its worth," said Titian.

[27] E. H. Blashfield in Italian Cities.

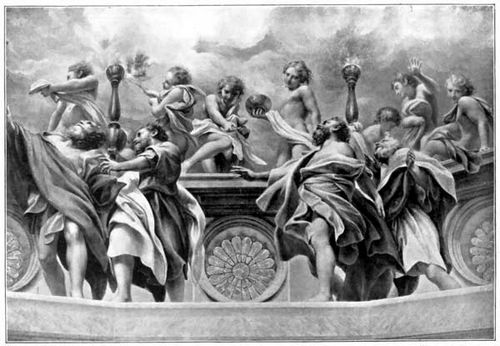

Our illustration shows a portion of the octagonal cornice. The design is a simulated balcony ornamented with tall candelabra. In front stand the apostles grouped in twos at the corners. On the top of the balustrade, in the spaces between the candelabra, sport a band of genii, or heavenly spirits.

The four apostles are men of giant frames with broad shoulders and stalwart limbs. They are of middle age, heavily bearded, and all look much alike. It would be impossible to call one Peter, and another Paul, or to identify any particular persons. Evidently it was not the intention of the artist to distinguish individuals. All the figures are turned with lifted faces towards the vision in the dome. Each expresses, by a gesture, the wonder, joy, rapture, or admiration aroused by the spectacle. Their attitudes are somewhat extravagant and self-conscious. The drapery, too, is rather fantastic, flung about their figures, leaving arms and legs bare. Were the picture taken out of its surroundings it would scarcely suggest a Christian subject. These colossal beings are like Titans moving through the figures of a sacred dance, and murmuring the mystic incantations of some heathen rite.

APOSTLES AND GENII

APOSTLES AND GENII But we must not press our interpretation too far. The panel should be studied for its decorative quality as a part of a larger scheme. Viewed from below, this procession of figures must be exceedingly effective. The emphasis of lines is diagonal, flowing in the direction of the focal point of the whole decoration.

The genii of the balustrade are beings of Correggio's own creation. His imagination called forth a world of spirits without a counterpart in the work of any other painter. Lacking the wings usually given in art to angels, they also lack the proper air of sanctity for heavenly habitants. Yet they are far too ethereal for mortals. Neither angel nor human, they are rather sprites of elf-land. With their tossing hair and agile motions they remind us of woodland creatures, and they look shyly out of their eyes like the furtive folk of the forest.

They are sportive, but not mischievous, in the human sense. They frolic in the pure delight of motion. By mortal standards of age they are between childhood and youth, when limbs are long and bodies supple. Their only draperies are narrow scarfs which they twist about them in every conceivable way.

Of the seven figures seen in our illustration, two only have any ostensible purpose to serve. One seems to be lighting a candelabrum with a flambeau; another carries a bowl which may be used for incense. The others are idlers. If they have any duties as acolytes, these are for the moment forgotten. Several are attracted by the ceremonies in the cathedral and look down from their high perch upon the worshipping congregation.

The sprite at the extreme right is seated, and peeps over his shoulder with a rather dreamy expression. Next come two who are playing together, one throwing up his left arm as if to balance himself. Beyond the candelabrum is one whose parted hair and coquettish pose of the head give a feminine look to the figure. The sprite in the centre of the balustrade is the most winsome of the company. His bright eyes have spied out some one in the congregation, and stooping, he points directly at the person. His expression is very roguish. The little fellow with the flambeau is at the left, and last is one whose face is turned away towards the imaginary space behind the balcony.

Our illustration gives us a general idea of Correggio's decorative method. The human body was his material; his patterns were woven of nude figures, posed in every possible attitude. Every figure is in motion, and the whole multitude palpitates with the joy of living.