The eccentric figure of Dr. Samuel Johnson was one of the familiar sights of London during the middle of the eighteenth century. He was a man of great learning, a voluminous writer, and an even more remarkable talker. He was born in 1709, and, the son of a poor bookseller, he struggled against poverty for many years. Literary work was ill paid in those days, and Johnson gained his reputation but slowly. He contributed articles to the magazines, and twice he conducted short-lived periodicals of his own—the "Rambler" and the "Idler." He wrote, besides, a drama, "Irene"; a tale, "Rasselas"; a book of travel, a "Journey to the Hebrides"; and many biographies, including the "Lives of the Poets." His largest undertaking was an English dictionary, upon which he spent eight years of labor.

At length his pecuniary troubles came to an end when, in 1762, the government awarded him a pension of £300 a year. By this time his great intellectual gifts had begun to be appreciated, and he was the first man of letters in England. In Thackeray's phrase, he "was revered as a sort of oracle."

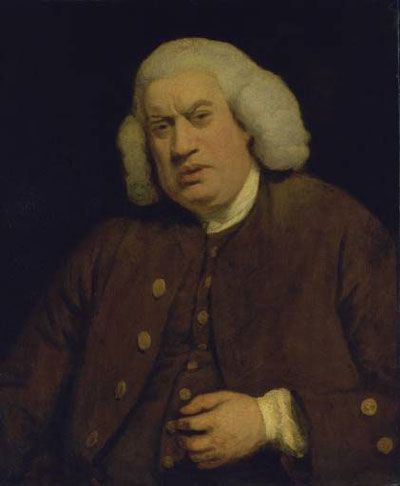

Johnson was now too old to acquire the graces of polite society, even had he wished them. His huge, uncouth figure and rolling walk, his countenance disfigured by scrofula, his blinking eyes, his convulsive movements, his slovenly dress and boorish manners made him a strange figure in the circles which entertained him.

His appetite was enormous, and he ate "like a famished wolf, the veins swelling on his forehead, and the perspiration running down his cheeks." He usually declined wine, but his capacity for tea was unlimited. Many funny stories are told of the number of cups poured for him by obliging hostesses, for, oddly enough, he was a great favorite with the ladies, and knew how to turn a pretty compliment. His temper was at times very irritable and morbid, and he occasionally had violent fits of rage. Yet, with all these peculiarities, he had a kind heart and was sincerely religious. His devotion to his wife and his aged mother[18] was very touching, and the poor and infirm knew his charities. In his own lodgings he provided a home for an oddly assorted family of dependents, consisting of an old man, a blind woman, a negro boy, and a cat. All the details of his daily life and habits are minutely described in a biography written by his admiring friend, Boswell, who was intimately associated with him for many years. The book he wrote after Johnson's death tells us not only all about the learned doctor, but much also about his friends.

[18] His wife died in 1752, and his mother in 1759 at the age of ninety.

Reynolds was one of his warm friends, and the two understood each other well. Often when they were together in company, the painter's tact and courtesy smoothed over some breach of etiquette on the part of his companion. At Reynolds's suggestion, the two founded together a small club of congenial spirits, called the Literary Club.

Some other good friends of Johnson's were the Thrales. Mr. Thrale was a rich brewer, and a man of parts, and his wife was one of the brightest women of her day. Johnson was a constant visitor at their house, and became at last, practically, a member of the family. The Thrales's drawing-room at their Streatham villa was the scene of many brilliant gatherings, where intellectual people met for conversation and discussion. Johnson was the autocrat of this circle. He was often rude, even insolent, in expressing his opinion, and wounded many by his sarcasm. But his vast stores of information, his keen mind and ready wit, made his conversation an intellectual feast.

It was an ambition of Mr. Thrale to ornament his house with a gallery of portraits of contemporary celebrities, and it was for this collection that Reynolds painted the portrait of Johnson, reproduced in our illustration. It was really a repetition of a portrait he had previously painted for their common friend and club-fellow, Bennet Langton.

Here we see the sage at the age of sixty odd years, precisely as he appeared among his friends at Streatham. The painter has straightened the wig, which was usually worn awry, but otherwise it is the very Dr. Johnson of whom we read so much, with his shabby brown coat, his big shambling shoulders, and coarse features.

A remarkable thing about the portrait is that Reynolds succeeded so well in showing us the man himself under this rough exterior. The inferior artist paints only the outside of a face just as it looks to a stranger who knows nothing of the character of the sitter. The master paints the face as it looks to a friend who knows the soul within. Now, Reynolds was not only a master, but he was, in this case, painting a friend. So he put on the canvas, not merely the eccentric face of Dr. Johnson as a stranger might see it, but he painted in it that expression of intellectual power which the great man showed among his congenial friends. Something, too, is suggested in the portrait of that sternly upright spirit which hated a lie.

It is a portrait of Johnson the scholar, the thinker, and the conversationalist. He seems to be engaged in some argument, and is delivering his opinion with characteristic authoritativeness. The heavy features are lighted by his thought. One may fancy that the talk turns upon patriotism, when Johnson, roused to indignation by the false pretences of many would-be patriots, exclaims, "Sir, patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel."